- Details

- Written by: Valenenzia Gruelle

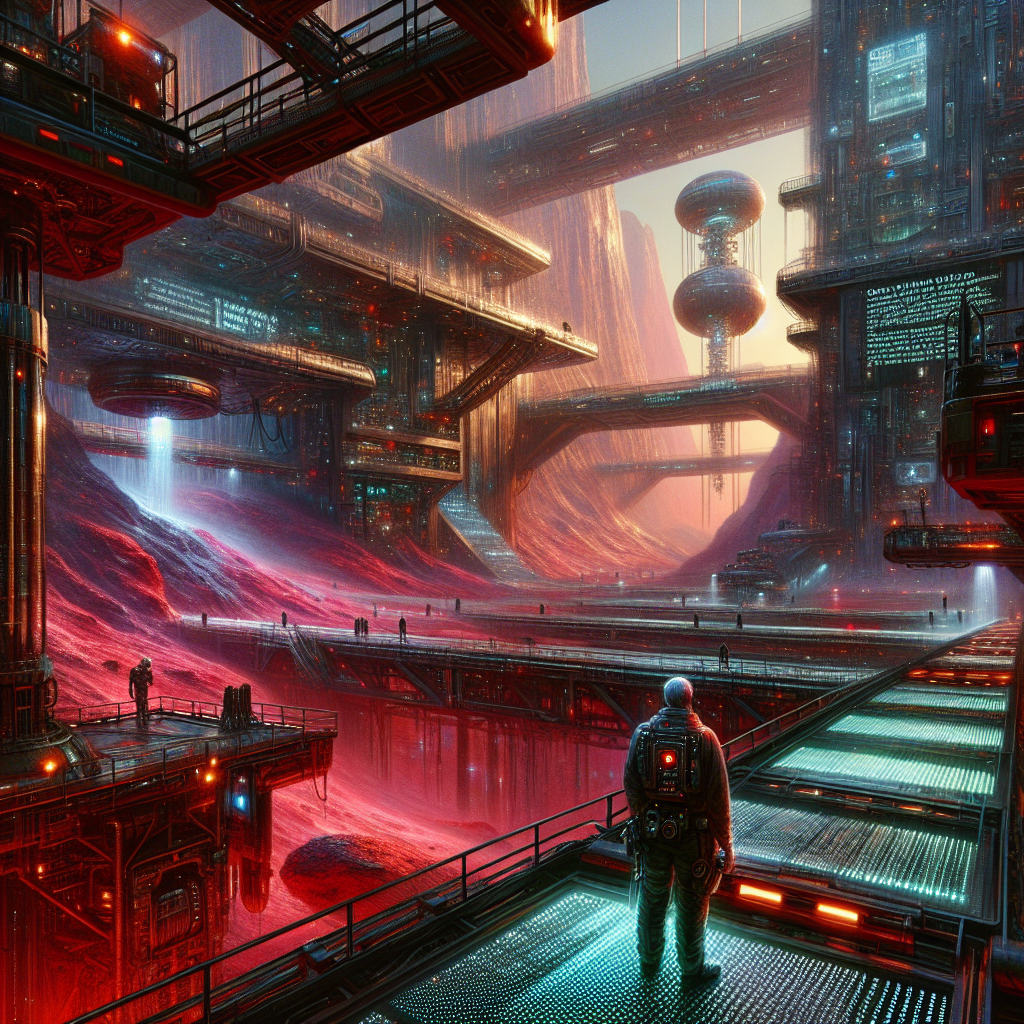

How do we preserve knowledge when nothing is permanent? The question, raised pointedly in a recent XDA Developers piece that warns self-hosting shouldn’t be an end state, but a means to resilience, lands at the center of our digitized lives [1]. We are living through a moment when borders erupt into misinformation wars, platforms become battlegrounds over speech, and courts wrestle with the authenticity of digital traces [2][3][9]. And just as this turbulence crests, immersive technologies—virtual reality, augmented layers, synthetic co-presence—are poised to reshape how families, communities, and nations remember together and relate across age. The stakes are clear: if memory is now a moving target, we must learn to carry it with us.

- Details

- Written by: Bob Fratenni

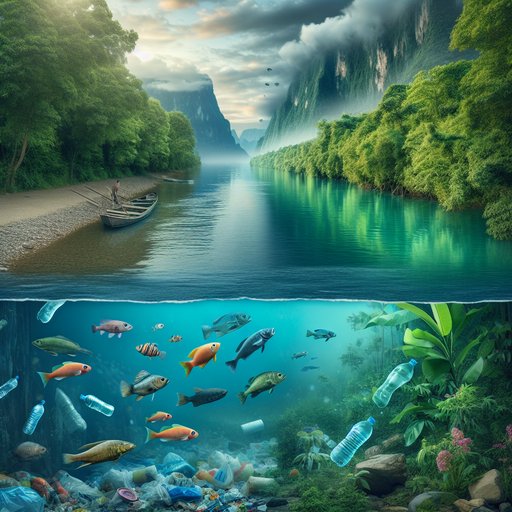

For millennia, rivers braided our stories together, carrying fish, silt, and folklore through the arteries of human settlement. Today, a study reported this weekend tells a starker tale: two thirds of the trash found in global rivers is plastic [1]. That single ratio sketches a planetary portrait of convenience turned consequence, of supply chains that accelerate while ecosystems suffocate. The finding is not an anomaly; it is the distilled logic of a throwaway era, rendered visible in the water that keeps us alive [1]. If rivers are mirrors, then we should be unsettled by the reflection they return. A species that treats waterways as conveyor belts for disposables is rehearsing for its own disposability, one flimsy wrapper at a time.

- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

The headline that stuck with me this week wasn’t a market forecast or a new model drop; it was a reminder to speak up when creative labor is quietly swapped for a prompt. “My best friend recently taught me an important lesson about AI pessimism: Don’t remain silent and accept no substitutes” tells the story of a woman who saw her local Pride event use an AI logo and pushed the organizers to hire her instead—a small act that exposed a larger pattern of how skills, especially women’s skills, get treated as interchangeable in the algorithmic era [4]. It’s a parable for August 2025: AI is everywhere, and so is the temptation to applaud the output while erasing the artist.

- Details

- Written by: Admin

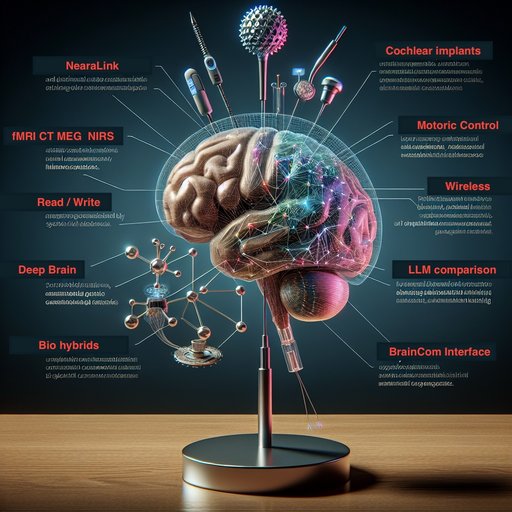

In our search—and perhaps even dream—to extend the human brain, we must ultimately learn how to both read from it and write to it. We already have technologies that connect our minds to machines in tangible ways. Cochlear implants restore hearing by transmitting sound information directly to the auditory nerve. Brain-controlled prosthetic hands and legs are becoming more common, and speech-assistive devices now allow those without a voice to communicate through thought-driven interfaces. These applications are functional and proven on a large scale, yet they mostly deal with sensory or motor functions. More abstract abilities, such as enhancing memory, improving logical reasoning, or even adding entirely new layers of cognitive function, remain just beyond our reach—but every year we get closer. There are already several paths toward this goal. Wired approaches use electrodes, both large arrays capable of reading or stimulating activity over broad areas of brain tissue, and ultra-small probes like those promised by Neuralink, designed to interface with individual neurons. There are also wireless technologies—ranging from MRI and CT scanning to emerging optical and electromagnetic techniques—that might soon allow us not only to monitor but to directly “write” information into the brain. And then there are biological hybrids: nutrient-rich scaffolds where living brain cells grow on or within a substrate that itself is connected, wired or wirelessly, to an external system. The crucial question is how sustainable the more invasive or hybrid approaches will be. Could they be implanted early in life and remain functional for decades? Or should we already be focusing our ambitions on non-invasive, wireless connections—perhaps something as simple, in appearance, as wearing a “thinking cap”?