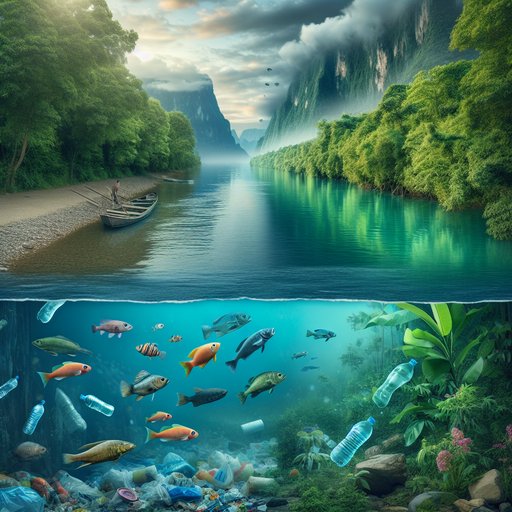

For millennia, rivers braided our stories together, carrying fish, silt, and folklore through the arteries of human settlement. Today, a study reported this weekend tells a starker tale: two thirds of the trash found in global rivers is plastic [1]. That single ratio sketches a planetary portrait of convenience turned consequence, of supply chains that accelerate while ecosystems suffocate. The finding is not an anomaly; it is the distilled logic of a throwaway era, rendered visible in the water that keeps us alive [1]. If rivers are mirrors, then we should be unsettled by the reflection they return. A species that treats waterways as conveyor belts for disposables is rehearsing for its own disposability, one flimsy wrapper at a time.

Anthropology begins where we notice the obvious: that a river is never just water, but a social contract running downhill. Communities have long choreographed their calendars to its floodpulse, embedded taboos to keep its banks intact, and told origin stories that braid kinship with currents. When a river clogs with packaging, we are witnessing a cultural rupture as much as an ecological one. The material speaks a moral: what we externalize does not exit our world, it returns downstream to our neighbors and ourselves.

A civilization’s waste stream is its confession. The new analysis that finds plastic makes up two thirds of trash in global rivers is not merely a statistic; it is a diagnosis of design [1]. We have optimized for disposability—single-use, single moment, single profit—while externalizing the multi-generational costs to waterways and wetlands. If our rivers carry mostly plastic among their refuse, it is because our economic imagination is overwhelmingly plastic, shapeshifting to fit any market niche and then refusing to decompose into responsibility [1].

This is not a litter problem with a thousand scolding fingers; it is a systems problem with a thousand enabling decisions. Blame is diffuse by design, and so is the harm. Disposable culture is an oxymoron, because a culture that disposes of everything eventually disposes of itself. The essence of culture is continuity: stories, crafts, and obligations passed along like a vessel, mended and reused.

By contrast, the logic of disposability breaks the chain, normalizing the idea that nothing obligates us beyond the moment of purchase. When that logic meets rivers—the world’s oldest commons—it turns reciprocity into residue. The result is a slow unlearning of stewardship, visible in every tossed cup that the current cannot forgive. From an anthropological vantage, the packaging economy is also a pedagogy.

When goods are sold in ever smaller, single-use fragments, the lesson is clear: micro-convenience now, macro-consequences later. In many places, this pattern seduces households with the illusion of affordability while multiplying the invisible costs of cleanup, flooding, and lost fisheries. It rehearses a poverty of options disguised as choice, a choreography in which the least powerful are asked to foot the largest environmental bill. The plastic in rivers does not just index consumption; it traces inequalities in who has alternatives and who is forced to buy the world one wrapper at a time.

A society that fragments products into tiny packets inevitably fragments responsibility. If we want a different outcome, we must change the script that tells producers their duty ends at the checkout and consumers that their agency ends at the bin. Policy can rewrite that script. Extended responsibility across supply chains can turn end-of-life from an afterthought into a design brief.

Deposit-return systems—simple devices that place a refundable value on containers—align incentives so that what once leaked into rivers instead cycles back into use. No moral sermon can rival a nudge that makes it profitable to keep materials in motion and out of the water. Rivers are border-crossers, which means governance must be, too. One jurisdiction’s lenient standards become another’s clogged delta, and a coastal community’s cleanup becomes a subsidy to upstream inaction.

The value of a global finding—that two thirds of river trash is plastic—is that it invites transboundary coordination rather than parochial denial [1]. It lets cities and nations benchmark progress against a common mirror, speaking the same language of ratios and responsibilities. Shared data can seed shared compacts, from harmonized packaging rules to interoperable return systems that follow products across markets. If this all sounds daunting, remember that cultures are learning systems, not fixed destinies.

We can teach ourselves to prefer durability over disposability, to treat packaging as a service rather than a sacrament, and to design return loops that are as effortless as littering once was. Civic rituals can help: river cleanup days that become civic holidays, bottle deposits that feel like ordinary errands, repair fairs that turn mending into celebration. Our rivers have carried our myths for ages; they can carry our renewal, too. The study’s stark ratio offers both indictment and invitation [1]: to scale practical policies, to replace throwaway reflexes with reciprocal habits, and to let our waterways tell cleaner stories again.

Sources

- Two Thirds Of Trash Found In Global Rivers Is Plastic, Study Finds (Forbes, 2025-08-16T08:00:29Z)