- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

The reports are stark, the details devastating: a 29-year-old news anchor died after falling from the third floor of her home while trying to escape armed robbers, a story relayed across outlets and shoved into our feeds with the blunt force of catastrophe [1][9]. In the attention economy, tragedies arrive as push alerts and thumbnails before they become human again. As an art critic who studies how forms of seeing shape forms of feeling, I keep returning to a hard question: when our encounters with loss become increasingly mediated—wrapped in high-definition video, algorithmic curation, even “immersive” storytelling—do we deepen our capacity for empathy, or do we simply perfect the choreography of looking away? The answer depends less on technology than on intention, context, and whether the design of our cultural interfaces honors the person beyond the headline.

- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

This week’s press note about iScreen’s full iOS 26 compatibility, bundled with “new creative features” and an “expanding global reach,” reads like a familiar drumroll for the tech‑culture parade [2]. It is an achievement worth acknowledging: compatibility is the plumbing that keeps creative practice flowing, and reach can widen audiences. But in 2025’s hype-bent attention economy, infrastructure announcements double as cultural positioning statements. They tell us not just what a tool does, but who it imagines as its makers, arbiters, and stars. If platforms want to be more than loudspeakers for the already‑loud, they must connect technical milestones to structural commitments, especially around recognition. Otherwise, “reach” becomes a megaphone that amplifies the same voices and mutes the rest.

- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

A trashed former hospital site in Newborough, near Moe, has hit the market after years of decay, with local voices calling for it to be converted into social housing rather than yet another speculative shell [6]. Real estate, yes—but also a referendum on what a community is allowed to say, stage, and remember while the wreckage still stands. As the sale sign goes up, so does a subtler placard: how do we protect people from hazards without silencing the art and testimony that often bloom in neglected places? The boundary between safeguarding and smothering expression rarely appears in zoning language, but in practice it can decide whether a town’s wounds are aired or quietly plastered over [6]. This is not a gallery spat; it’s a civic syllabus on who gets to narrate decline and design the future.

- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

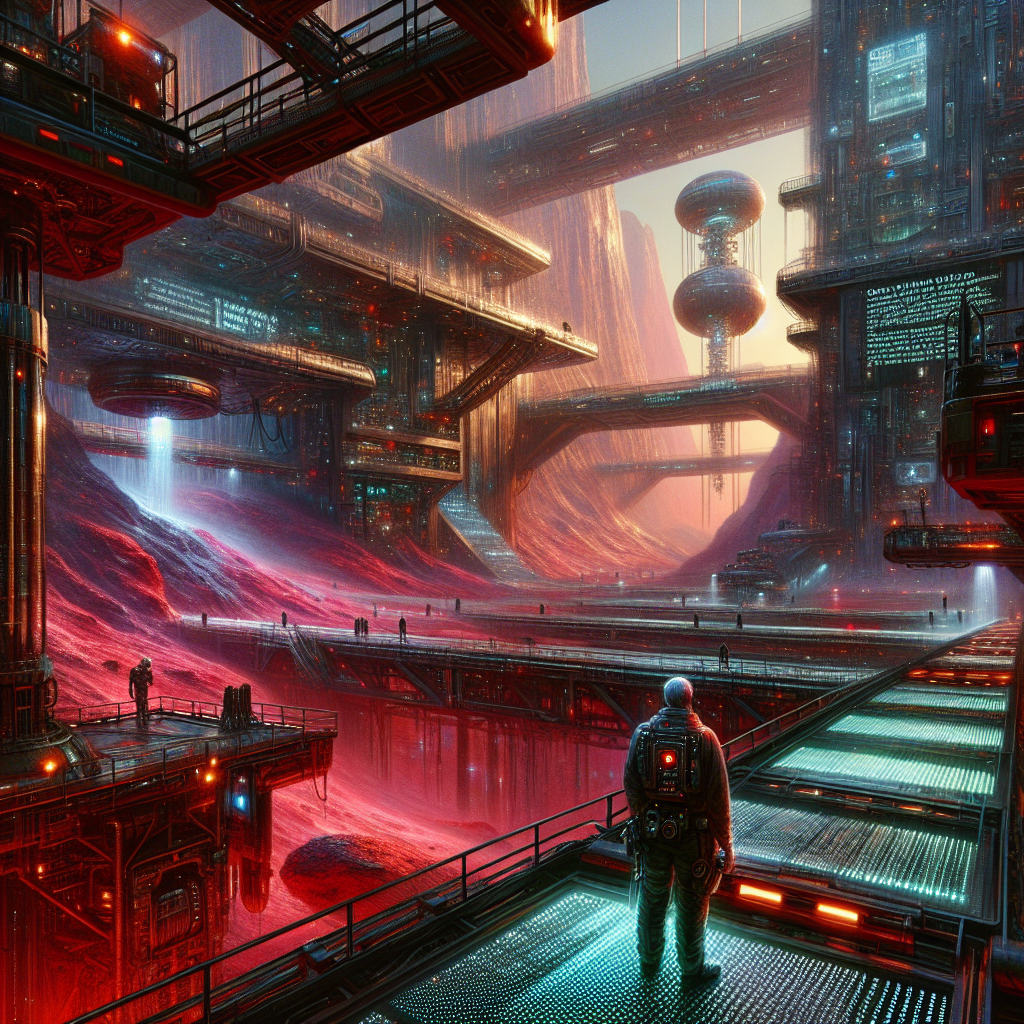

A feature titled “Between Reality and Emotion: The 3D Storytelling of Célia Lopez” arrives with exquisite timing, reminding us that the most urgent canvases today are not just screens, but cities themselves [9][10]. The phrase in that headline distills the core tension of public art: we navigate facts underfoot and feelings at eye level, and we want art that can hold both without flattening either. As mobile tools for professional capture expand—Apple’s Final Cut Camera 2.0 now supports new iPhone 17 lineup features, with further updates for the iPhone 17 Pro noted this week [1][3]—the pipeline from concept to city wall is shorter than ever. The question isn’t whether 3D storytelling can reach the street; it’s whether, once there, it will diagnose civic health or merely decorate it.