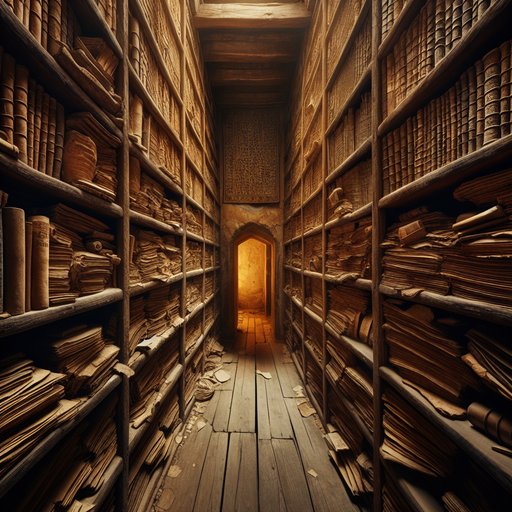

At closing time, when the lights of the city falter and settle into their long, sodium exhale, I slip into the library that keeps a little of every age. It is not a grand cathedral of knowledge but a narrow place with uneven floorboards and shelves that listen. I come because I am thirsty, and I do not know for what. In the low light, tablets and scrolls, sutras and codices lean toward one another like tired travelers telling stories they cannot finish. I put my hand on a cracked clay shard and feel heat, not of the bulb above me but of a hearth too old to remember. The room breathes, and the distance between then and now collapses like a tent taken down at dawn.

Smoke rises in the first room I step into, a home without walls, wind-bent reeds around a circle of fire. A woman grinds barley with both hands, the pulse of the stone like a measured heartbeat. She hums, not to a god with a name, but to the sky that will not make promises. When thunder rolls across the plain, her youngest presses his face into the crook of her knee.

She cups ash and oil, smears a simple mark on the lintel. Later, her neighbor's cow births a calf and bleeds too much. They carry water, they press cloth, they try and they fail, and at night they raise their hands and say the same word for gratitude and fear. Something shifts: the gesture tells a story longer than the day.

A river dawn follows, clear and gold. Along its bank a young man with smoke in his hair stirs coals until they bloom. He sings to the fire, not because fire needs praise, but because his own breath does. He calls it friend and messenger and begins to suspect the messenger is within.

He has seen the horse lathered, the seeds burned for favor, the bargains struck with what cannot be bargained with. Now his voice softens: the rightness he seeks is like the river's course, a structure that holds without grasping. The word he uses for order tastes like both rule and rhythm. He feeds ghee to flame and then, unexpectedly, sits without feeding anything.

The first altar recedes; the spine becomes an altar no one else can touch. His teacher, pleased and wary, whispers that the way you tend your attention becomes the world you live in. Far west, a gate creaks open on a windswept hill. Two shepherds argue over a lamb, and the elder at the gate, who carries grief under his robe like a weight he has chosen, says the land belongs to none of them.

He points to the margins where women are gleaning the edges of a field and says, leave it, leave that for the ones without inheritance. In the marketplace he refuses to kneel before carved wood, not because the wood is offensive but because it cannot be what bound him to a promise. He tells the child at his knee a story of leaving a house with walls that rose like god-kings and walking out without a map. He insists memory must be thick enough to protect the stranger, that justice is not an idea but bread walked to a doorstep.

He names the one behind the many winds and binds his people not with iron but with a seven-day rhythm, a rest that refuses the economy of empire. I turn and the ground cools to shade beneath a wide fig tree. A man sits cross-legged, bones like reeds left by a flood, and his eyes do not fix on the jut of a palace spire or on any altar. A mother kneels in front of him with a little shoe that no longer has a foot in it.

He does not promise her the child returns; he does not offer a name to demand from heaven. He asks her to breathe with him. The breath reveals what it always does: the mind leaps, clutches, burns, again and again. He teaches the way to notice the leap and soften the clutching.

He touches the earth, not to claim it but to let it witness that he did not run from his own pain. When he stands days later, he leaves no creed written in stone, only a pattern of practice and a wheel that will roll across mountains on the backs of those who choose to sit and then to stand with a quieter hand. At the foot of a worn city wall, two old men argue whether grief should last three years or be measured according to the harvest. The younger, who is actually older, keeps returning to the way a son should bow, not for the sake of the bow but for the shaping it performs.

He insists that to do the forms without the heart is to be a reed flute with no wind. Nearby, down a sandy path, a fisherman laughs by himself as water curls around his ankles. He holds a crooked piece of wood and says the crooked survives the storm. He refuses the names that stick to things and calls what he follows water's patience.

The one with the rites and the one with the nameless way walk the same street at different times. Between them a woman lays out bowls for ancestors and teaches her daughter to hold them as if she is carrying a sleeping bird. Order and ease, rectification of names and refusal to catch them — two answers to the same ache to be aligned with the way things are without being crushed by them. Now a courtyard glows with the light of oil lamps, and the aroma of herbs sneaks out the door to the alley.

A woman breaks a jar over a teacher's feet; the smell filigrees the room until every eye waters. The men at the table protest, counting cost, counting the poor, counting in general, while the teacher says nothing and looks at the woman as if he has found the thread he has been pulling for years. He will die on a hill that pretends to be a warning and will become a hinge. In the nights that follow, bodies crowd into houses and re-enact a meal where bread breaks and means more than bread.

They carry sick neighbors, and not all of them are healed, and they keep carrying anyway. They say that power now tilts downward, that the axis of the world has been redrawn to pass through the low and the left out. They gather in secret and sing like people who have been reversed. Wind moves like an ink stroke across a rocky gorge.

A trader, used to numbers and routes and the texture of cloth between his fingers, is pressed to the ground by words that do not feel like his own. He does not want to carry them; he cannot keep them. He recites what recites him. The syllables burn and cool, instruct and comfort, warn against hoarding and against forgetfulness.

Later, in the market, he puts his thumb on the scale and then removes it. He stands shoulder to shoulder with a freedman and a chief and an orphan in thin sandals, all lined toward a direction that is half compass and half desire. The book that will come is first a voice, then a binding, then a conversation as wide as a caravan route. Law grows from mercy and memory, not as a chain but as a fence that keeps the weak from the teeth of the strong.

Centuries begin to behave like days. In a painted cell, a monk places gold leaf on the cheek of a saint and blinks at the light. In a madrasa, a jurist measures the fairness of a contract and then walks to the market to watch whether his measurements hold against the noise of barter. Under a tree, a poet sings to a dark-fluted friend and scolds him with the insolence of love.

In a cold monastery, a scholar scratches notes in margins, arguing with a bishop he will never meet. In a mountain hall, a teacher whacks a table with a stick and laughs until his students do not know whether the sound itself is the teaching. In a courtyard, a dervish turns, and the dust rises in spirals. Empires borrow the language of devotion for their banners and ask swords to do what prayers cannot.

A press hammers type into paper, and the room fills with ink and disagreement. In a port city, traders of doctrines and almonds share a jug and argue until the lamps burn low, then pour the last cup evenly. I step back and the door throws me into a hospital hallway where beeps measure a life more precisely than any candle. A nurse hums a psalm while taping a line to a trembling arm.

In a different ward, a woman counts breaths with a string of knots while a man in a black hoodie mutters a prayer he learned from his grandmother into the glow of a phone. Outside, a procession chants names of the dead and demands laws bend toward the living. Elsewhere, a scholar reads scripture against a screen of data, not to flatten it but to see if mercy has a method. In another place, a boy kneels on a rug pointed toward a city he cannot return to and asks that the walls in his chest be softened.

A girl leaves fruit at a roadside shrine and does not take a picture. All the paths continue, twisting, braided, frayed. Their arguments sharpen and birth kindness and harm, both. Their questions deepen: not how to win, but how to be well among strangers.

Back in the library, the dust has settled across open pages like a fine, democratic fog. The clay shard warms my palm as if someone has just blown on it. I cannot mark a clean beginning; there is no point where silence ends and prayer begins, only gestures that learned to continue themselves. A mark on a lintel becomes a law, becomes a song, becomes a vow that makes marketplaces more honest and tables more open.

A protest against idols becomes a covenant that insists on care for the one without a name in the book. A quiet sitting becomes a way to meet pain without inventing enemies. A meal reenacted becomes a slow revolution in power. A recited night becomes a day shared by many who would have killed each other yesterday and sometimes still try.

The thread is not doctrine but thirst: for meaning, for justice, for company in the face of a mortality that never stops telling the truth. When I leave, the street is wet and empty, and the sheen of it holds the city upside down. The argument between my solitude and the songs of others softens into something I am less eager to resolve. Origins, it turns out, are habits we keep repeating until they become us.

Development is an ongoing choice about which habits to inherit and which to burn for light. The first philosophers were people who stirred a pot and asked whether the stew needed salt or just patience. The major religions, under their banners and buildings, are schools for learning to receive and to refuse. I enter the rain and think of the woman smearing ash on her doorframe, the sage feeding his breath to a fire, the shepherd leaving unharvested corners, the wanderer touching the ground.

I think the question is itself a prayer: how to live so that our thirst does not turn us into thieves.