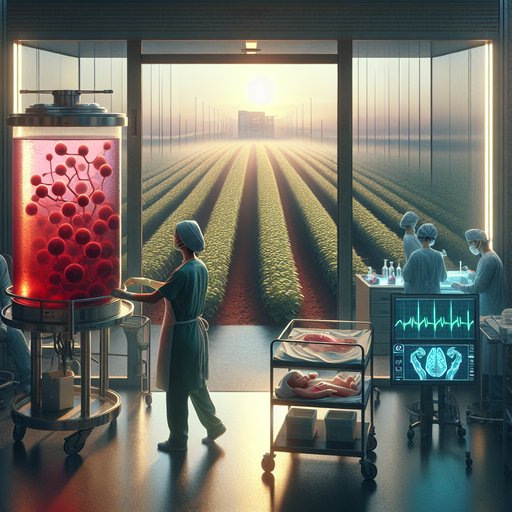

In a hospital room that smells faintly of antiseptic and citrus cleaner, a nurse wheels in a bag of a patient’s own blood stem cells—now edited with a molecular scalpel that was a lab curiosity just a decade ago. At another hospital, surgeons watch a gene-edited pig kidney pink up inside a human body, while cameras catch the moment a machine learning model proposes a safer way to make a change in DNA without breaking the strand clean through. In farm plots marked by colored flags, seedlings bred by precision rather than cross-pollination rise into heat that does not let up. The breakthroughs of the past year do not announce themselves with triumphal fanfare so much as the hum of pumps, the glow of monitors, and the quiet recalibration of what medicine, agriculture, and biology expect from the alphabet of life.

The infusion pump clicks and the edited cells drip back, the crimson line feeding a body that has learned pain on a schedule. Sickle cell disease does that. The patient’s mother keeps glancing at a latex-gloved hand holding the tube as if it is a tether to a future that finally stops snapping back. The room is busy in a practiced way: a pharmacist checking a chart, a clinician asking about appetite, a researcher observing in silence because consent requires presence.

Last winter, regulators in the United States and United Kingdom approve the first CRISPR-based therapy for sickle cell disease, the culmination of years of methodical trial work. This moment is medicine rendered as an edit, not an addition, a deliberate tweak to coax fetal hemoglobin back into service. Down the hall, the alternative is visible in the curve of a chemotherapy chair. Conditioning is brutal and necessary, a clearing out of marrow to make space for the edited cells to take root.

The price tag hovers over the scene like a second IV bag: a figure in the millions, negotiated by insurers, governments, and families who have been counting hospital nights for years. Staff are careful not to call it a cure in the definitive sense, even as they say the word with hope. Access is not just a question of money; it is geography, it is transplant infrastructure, it is whether the clinical trial ever opened a site near where people actually live with this disease. Across town, in a lab filled with refrigerators that exhale and incubators that glow, the newer tools are being weighed like knives on a chef’s board.

Base editors that swap single letters without making a double-strand break sit beside their younger cousin, prime editors that carry a template for more precise fixes. A graduate student scrolls through a visualization that turns off-target risk into a heat map; the screen bleeds cool blues and anxious reds. A postdoc touts a system that writes larger segments without relying solely on blunt breaks or viral cargo—names like PASTE and CAST that sound like they belong in a workshop. The emphasis is on finesse: on changes that nudge rather than gouge, on edits that stay put, on the kind of molecular handwriting that looks like the native script.

Delivery keeps tugging the conversation back to biology’s logistics. A lipid nanoparticle is, in the end, a vehicle; a virus is a courier with a personality and limits. Engineers tweak charges and shapes to direct these couriers to liver, to marrow, to muscle, to the deep archipelago of the brain. There are experiments that favor RNA over DNA, trading permanence for flexibility, choosing to quiet a gene for a while rather than rewrite it forever.

Clinicians talk about the BCL11A switch with the affection of people who have learned where the building’s breaker box is; flipping it to unlock fetal hemoglobin is more than a trick, it is a kind of rediscovery. The new ethos is to touch lightly and leave a trail of evidence that can be audited later. In a surgical theater lit like a film set, a kidney from a pig is carried in, its surface shining with perfusate. The animal it comes from is a product of design as much as husbandry, its genome retuned to evade the immune tripwires that make xenotransplantation so fraught.

Monitors stutter to a steady rhythm as perfusion restarts; there is a collective exhale when urine drains clear. The surgeon’s voice is measured when she explains to a family what dozens of edits are for: to reduce rejection, to prevent a mindless immune cascade, to buy time. This is a milestone year for that work, a proof that the line between “animal” and “donor” is not fixed but negotiated. The person on the table is not an abstraction, and neither are the unknowns about how long this organ will endure.

Several counties away, a field trial fence hums with insects, and under it, plants that never knew a gene gun lift their leaves to hard light. These are not transgenic in the way that triggered early twenty-first-century backlash; they are edits within a genome’s own repertoire, changes that would be plausible if nature had all the time in the world and a different set of dice. In England, new rules for so-called precision breeding ease the path from greenhouse to field, and breeders speak about disease resistance and climate resilience like they are urgent and ordinary. A small company shares data with a growers’ cooperative, mindful of optics and of the fact that trust grows slowly.

On the hedgerow, a biodiversity advocate watches pollinators and asks where the consent process lives when pollen crosses a ditch. At a community health center, a patient leader spreads a thick folder across a folding table: lab results, trial consent forms, notes from support groups. They have learned to translate between researchers, insurers, and families with a clarity that makes people cry. The approvals are welcome, but the fine print is relentless—eligibility criteria that exclude as much as they include, lab capacity that turns a national breakthrough into a local waitlist.

Price is a moral force here. Negotiations produce numbers that begin with a two or a three and are followed by six more digits; a rival therapy based on a different vector lands higher still. In questions after a town hall, someone asks whether a cure you cannot get is a cure or a new kind of absence. Back in the labs, the conversation turns to lines that must be drawn.

Embryo editing is a closed door in most jurisdictions, the handle taped over by consensus and by memory of a breach that jolted the field a few years ago. Gene drives—CRISPR harnessed to bias inheritance—remain corralled in cages and models, the promise of eradicating malarial mosquitoes shadowed by worries about irreversibility. Researchers talk openly about community consent, not as performance but as method; meetings are held in school gyms and under mango trees long before permitting is ever sought. International bodies publish guidance that reads like a scaffolding rather than a verdict, and in the margins, ethicists scribble notes about accountability that do not fit into a supplementary file.

Computational models sit beside pipettes now. Software suggests guide sequences, predicts off-target sites, and proposes new nuclease scaffolds that are smaller, stealthier, easier to smuggle into a cell without provoking alarms. A bench scientist toggles between a protein structure and a slide deck for a grant review; the line between simulation and synthesis tightens. There is a lively subfield in editing without cutting, in turning genes on and off with epigenetic switches that remember and then forget.

A neurologist wonders aloud what a reversible edit could mean for diseases where time is as much an enemy as pathology. The tempo of discovery is faster than the old pipeline allowed, but in the better labs, the speed is tempered by a habit of pausing to audit what the models missed. It is tempting to narrate all this as a triumph, to say that DNA editing is finally what it has long promised to be. Standing in the infusion room, the story refuses that shape.

The mother still counts minutes by the sound of a pump. The transplant nurse still watches for fevers at 3 a.m. The farmer still fingers a drought map with calloused hands. The surgeon still measures the day in creatinine levels and phone calls.

Progress here is a series of edits to a living draft, each change tracked in a margin that society will read and annotate as well. When the bag empties and the tube comes free, the patient’s mother exerts the smallest pressure with two fingers on a cotton ball. It is an ordinary gesture that feels like a closing parenthesis. Outside, the sky is indifferent, the same hard blue over the trial plots, the research campus, the transplant ward.

The technology settles in: less a revolution than an accrual, less a finish line than a learned practice. What we allow, what we fund, what we ask of consent and of risk—these are the edits that define the draft as much as any base change. The year DNA editing enters our lives, it does so with evidence, with argument, and with the understanding that the next revision is already on someone’s bench.