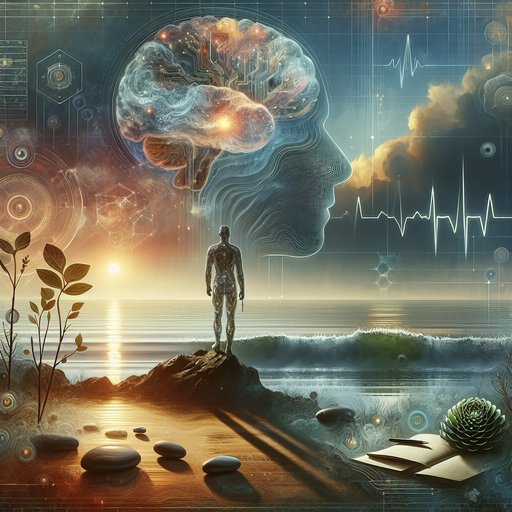

Psychological resilience is not a fixed trait reserved for a lucky few; it is a set of capacities that can be strengthened with practice. Researchers describe it as adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, or significant stress while maintaining or regaining mental well-being. In a world of constant change, burnout, and information overload, learning how to regulate emotions, think flexibly, and recover after setbacks is both a personal and public health priority. The science now maps resilience across biology, psychology, and social context, showing why some strategies reliably help people stay steady and grow under pressure. This article distills key mechanisms and practical, evidence-informed practices you can use, while encouraging collaboration with healthcare professionals for individualized guidance.

Chronic stress, uncertainty, and rapid technological shifts have made emotional volatility and exhaustion more common, with downstream effects on sleep, relationships, and work. Resilience matters because unmanaged stress raises allostatic load—the wear-and-tear on the body from repeated activation of stress systems—while effective coping promotes faster recovery. Importantly, resilience is dynamic and context-dependent: people can be resilient in one domain and struggle in another, and it changes over time with training and support. Seeing it as a trainable capacity replaces the myth of invulnerability with a more humane and practical goal: better stress responses, wiser strategies, and steadier recovery.

Biologically, resilience reflects how efficiently the brain and body mobilize for challenge and then return to baseline. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and autonomic nervous system coordinate that response, and a useful marker is heart rate variability (HRV), which is higher when the nervous system flexibly adapts to changing demands. Neuroimaging studies show that engaging prefrontal regions during cognitive reappraisal can dampen amygdala activity, supporting calmer behavior under stress. Plasticity means these circuits can be shaped over time, so practices that improve regulation can translate to measurable changes in stress physiology.

Psychologically, resilient people tend to use strategies that reduce harm without avoiding reality. Cognitive reappraisal—rethinking a situation’s meaning—consistently lowers negative affect and physiological arousal compared with suppression, which often backfires. Acceptance-based approaches help people face difficult internal experiences without getting stuck in struggle, enabling values-guided action even when discomfort is present. Positive emotions are not just pleasant; research on the broaden-and-build theory suggests they widen attention and help people discover resources and solutions, increasing the odds of adaptive coping when pressure mounts.

Social connection is a powerful buffer against stress, influencing both perception and biology. Large cohort studies link strong, supportive relationships with better mental health and lower mortality risk, and experiments show that supportive presence can reduce threat-related neural responses. Social baseline theory proposes that humans are wired to conserve energy when support is near, which makes practical sense: problems feel smaller when shared. Building reliable networks—through reciprocity, consistent check-ins, and participation in meaningful groups—creates a safety net that makes individual coping strategies more effective.

Foundational behaviors make advanced skills work better. Regular physical activity, especially moderate aerobic exercise, is associated with lower stress reactivity and improved mood in randomized trials, and even short bouts can help. Sleep is essential for emotion regulation; sleep loss biases the brain toward stronger emotional reactions and weaker prefrontal control, while consistent sleep and wake times support stability. Nutrition influences stress biology and mood via energy availability, inflammation, and the gut–brain axis; dietary patterns rich in whole foods are associated with better mental well-being in observational studies, and some randomized trials suggest dietary improvement can reduce depressive symptoms in some participants.

Hydration, sunlight during the day, and limiting late-night light create a physiological backdrop that favors resilience. Trainable skills translate science into daily leverage. Mindfulness training—such as mindfulness-based stress reduction—has been shown in randomized studies to reduce perceived stress and improve emotion regulation, partly by strengthening attention and metacognitive awareness. HRV biofeedback teaches slow, paced breathing around six breaths per minute, increasing vagal activity and improving autonomic flexibility; trials report benefits for stress and anxiety symptoms.

Stress inoculation training and graded exposure gently build tolerance to challenge, while cognitive-behavioral tools like implementation intentions (“If X happens, I will do Y”) and WOOP (Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan) improve follow-through under pressure by pre-loading adaptive responses. Turning principles into routines works best when challenges are matched to current capacity. Deliberately choosing tasks that are slightly above your comfort zone, followed by recovery and reflection, builds confidence without overwhelming you. After-action reviews—briefly asking what went well, what was hard, and what to adjust—convert experiences into learning, accelerating improvement.

Self-compassion predicts persistence after failure by reducing harsh self-criticism, and values clarification helps prioritize what matters when time and energy are limited, making it easier to say no to low-impact demands. Resilience is not the absence of pain or difficulty, and it is not an endless personal resource; it is a set of skills and supports that can be renewed. For some challenges, especially persistent mood changes, traumatic stress, or substance use, partnering with licensed mental health professionals is appropriate and often necessary. Communities, schools, and workplaces also shape resilience by setting reasonable demands, offering psychological safety, and providing access to resources.

By aligning biology, behavior, and social support—and by seeking professional guidance when needed—people can recover faster, adapt more wisely, and continue to pursue meaningful goals even when life is hard.