Rock ’n’ roll didn’t just erupt; it organized itself around a sound, a silhouette, and a stage. When Buddy Holly stepped beneath the lights of The Ed Sullivan Show in 1957 with a sunburst Fender Stratocaster, he brought a new blueprint into American living rooms: two guitars, bass, and drums driving original songs with crisp rhythm and melodic bite. The Stratocaster’s sleek contours and bright, versatile voice matched Holly’s economical phrasing and buoyant songwriting, translating teenage electricity into a clear, modern language. In that moment, a regional youth music became a national idiom, and an instrument designed for working players became a symbol of possibility for anyone with a garage, a small amp, and a few chords.

To understand why this moment matters, consider how a democracy negotiates culture in public. Mass media in the 1950s acted as both a platform and a gatekeeper, amplifying youthful expression while smoothing its edges to meet broadcast standards. Rock ’n’ roll faced moral panics, network caution, and the commercial sorting of what was deemed acceptable, yet it also benefited from broad access to radio and television that only a pluralistic society could provide. Holly’s appearance showed that within those constraints, a clear voice, a well-built guitar, and a tight band could still make a seismic statement.

The Stratocaster that Holly held was itself a product of democratic design. Leo Fender and his team in Fullerton released the model in 1954 after consulting working musicians like Bill Carson, prioritizing comfort, serviceability, and reliable volume over frills. Its contoured body, bolt-on neck, and three single-coil pickups were pragmatic innovations for crowded dance halls and long sets. Priced for gigging players and built with interchangeable parts, it helped level the field for musicians outside big studios and elite circles.

Buddy Holly seized on that promise early. In 1955 he acquired a Stratocaster from a Lubbock music shop and quickly folded its clean attack and sustain into his emerging style. At Norman Petty’s studio in Clovis, New Mexico, the guitar’s clarity carried the snap of his chords on ‘That’ll Be the Day’ and the percussive accents that defined The Crickets’ arrangements. The Strat wasn’t a prop; it was the engine of a band that made concise, original songs feel both intimate and radio-ready.

On December 1, 1957, that engine rolled onto The Ed Sullivan Show. With The Crickets behind him, Holly sang ‘That’ll Be the Day’ and ‘Peggy Sue’ to a national television audience, the Stratocaster riding high against his black suit like a badge of new music. The performance beamed the band blueprint into countless homes, showing that songwriting and guitars—rather than crooners, orchestras, or novelty gimmicks—could command prime time. It was less about showy theatrics and more about parts snapping together: driving drums, economical bass lines, tight rhythm, and the Strat’s articulate chime.

Technically, the Stratocaster broadened what Holly could say in three minutes. Even with the era’s three-position switch, he exploited the in-between pickup settings players discovered, getting glassy rhythm textures and cutting leads without changing instruments. Its synchronized tremolo bridge offered shimmer when needed, but Holly’s restraint kept the songs punchy and clear, allowing the lyric and groove to lead. The result was a sound that worked on primitive television speakers, car radios, and jukeboxes alike, an adaptability that helped rock ’n’ roll cross regional and generational lines.

The influence spread quickly, especially across the Atlantic. British teenagers saw photographs and broadcasts of the Strat held by a bespectacled songwriter who also fronted his band, and they took notes. The Crickets’ two-guitars-bass-drums format became the template for later groups; The Quarrymen—who would become The Beatles—cut a rough version of ‘That’ll Be the Day’ in 1958, a direct nod to their Texas hero. As more players adopted solid-body electrics, the Stratocaster’s look and sound became a passport for aspiring bands who wanted to write, arrange, and self-identify as modern.

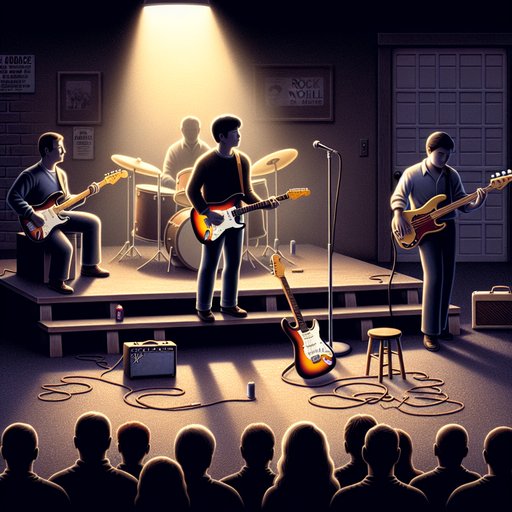

This was cultural democratization with real limits and real possibilities. Radio playlists and television slots were finite, and payola scandals underscored how commercial pressures shaped what the public heard. Yet the very visibility of Holly’s performance, and the availability of mass-produced instruments like the Stratocaster, meant that access wasn’t confined to conservatories or industry insiders. The ethic of do-it-yourself bands—learn a few chords, write a song, rehearse in a garage—rode the same currents as the broadcast that carried Holly’s voice.

Holly’s life was brief, but the image of that night endures because it captures rock ’n’ roll at the moment of self-definition. A songwriter with a modern electric, a band that played arrangements as tightly as pop standards, and a television platform willing to feature them—together they affirmed that youthful innovation could coexist with mainstream scrutiny. From there, the Stratocaster continued its journey through surf, blues-rock, and psychedelia, but its first great national statement had already framed what the instrument could mean. Decades on, when a young player straps on a Strat and counts in a band, they’re stepping into a lineage traced to a bright Sunday broadcast where rock ’n’ roll learned to speak to everyone at once.