Iconic is a word that bends under overuse, but some shapes refuse to let it collapse. The Porsche 911 has traced the same curve for six decades: a hood that falls away like a horizon, a roofline that arcs and slides, a tail that hints at the engine hiding behind the axle. This is not a legend told from barstools, but a history stamped in aluminum and magnesium, measured in rally stages, lap charts, and the steady hum of everyday commutes. Conceived in the early 1960s and constantly refined since, the 911 has endured shifting regulations, changing fuel, and new expectations for safety and efficiency. Its story is the persistence of an engineering idea—and the quiet stubbornness of a silhouette that keeps working.

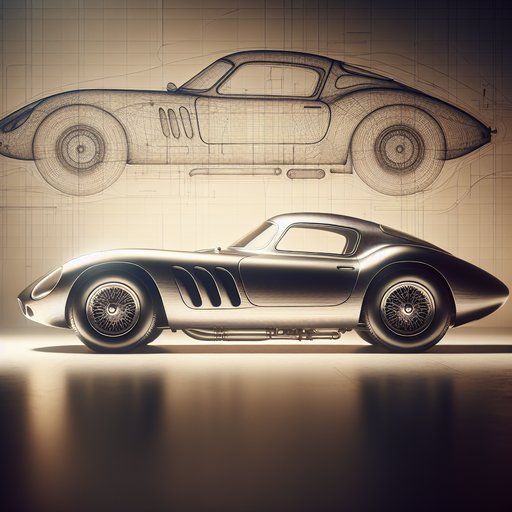

The doors to the Frankfurt show floor opened in 1963 and a small crowd formed around a low car with high shoulders. It wore the name 901 and the knifed crease of the front fenders cut the lights into bright ribbons across its paint. Ferdinand Alexander “Butzi” Porsche had sculpted its lines with the blunt logic of aerodynamics and the intimacy of handwork, the roof tracing an unbroken curve that rendered frames and pillars almost shy. The engine at the back was an air-cooled flat-six, earning its keep with fan noise and cleanliness of design, and when the stand staff rolled it through the aisle at closing, the scent was warm oil and new rubber, the old smell of possibilities.

On the autobahn near Zuffenhausen, early test drivers logged miles at dusk. They ran tall gears and the engine’s howl slid into a metallic drone that pooled behind the cabin glass. Peugeot claimed the 901 name and the badge became 911 before customers took their keys, but the car itself didn’t flinch. In the factory, torsion bars and trailing arms lined up with the calm of a drafting table, while body shells moved like chess pieces from booth to booth.

It had the elegance of a simple machine: minimal intake plumbing, a fan shroud like an industrial sculpture, and a body that the wind seemed to understand. Snowbanks along the Col de Turini swallowed wheels in the late 1960s, and winter turned rally teams into civil engineers. A 911 punched through the stage time sheets there, Vic Elford nursing speed out of traction that shouldn’t have existed, Denmark and Germany and France watching on black-and-white screens. The rear-engine weight over studded tires bit into ice and the long nose flicked, settled, and flicked again.

At service parks there were quick releases for extra lamps, tape lines across fenders, and mechanics warming their hands over exhaust pipes. The car gathered a reputation for making grip out of doubt, and it carried that trick onto gravel the size of fists in East Africa, suspensions lifted, stone guards fitted, the script on the decklid caked in dust. In 1972, the wind tunnel at Weissach pushed back with math. The tail lift on early cars had always been a quiet conversation; now it became a chart the engineers could argue with.

The response was a tapering blade of fiberglass on the engine cover, the first factory rear spoiler on a 911, and the name Carrera RS 2.7. Its ducktail was more than styling—lift dollars traded for downforce pennies, just enough to make the rear speak a little more clearly at speed. White cars with colored side stripes left showrooms faster than sales managers expected; the homologation count ticked upward as demand bent the plan. In 1973, a 911 Carrera RSR turned winter testing into victory at Daytona, and a few months later the road car’s silhouette, swollen with race intent, negotiated Sicily’s stone villages and switchbacks to win the Targa Florio overall.

By the time impact bumpers arrived in 1974 to meet U.S. regulations, the 911 had already learned to adapt without losing its face. Turbocharging hit the car like a weather change in 1975. The 930’s big tail—less duck, more whale—sat over a fan and a maze of pipes that took heat and turned it into thrust.

Boost built, then arrived all at once, a mechanical punch that dragged the horizon forward. Autobahn slip roads compressed into fast-forward; drivers learned respect the way they always did, by feeling edges rather than reading about them. Through the late 1970s and 1980s the Turbo was both ambassador and dare: a billboard on four wheels that insisted the 911’s peculiar layout still had real speed left to show, if you could keep your inputs honest. The decade that invented Group B also invented the 959, and although its bones differed, it was a manifesto for Stuttgart’s way of doing difficult things.

Fuel injection grew nuanced, all-wheel drive became an algorithm on wheels, and electronics began to shoulder work once left to elbows and instincts. In 1986 a 959 won the Paris–Dakar Rally, a line drawn across a continent by a machine that danced over perforated landscapes. Back in endurance racing, the 911’s silhouette stepped into the shadows of the 956 and 962 prototypes, yet a 911-derived 935 had already claimed Le Mans outright in 1979, and customer teams kept finessing 911s into class victories with garages full of spares and a rolodex of night watches. When the 964 generation landed in 1989, it folded some of the 959’s lessons into the family: ABS rudely interrupted lockups, power steering shortened arm-wrestling matches, and the Carrera 4 put driveshafts under the floor, broadening the car’s usable weather.

Late in the air-cooled era, the 993 stood like a final poem in a familiar meter. The body ironed its fenders smooth and the suspension traded the old rear architecture for a multi-link setup that soothed the 911’s spikier reflexes without dulling them. Inside, the five gauges still sat like stern witnesses, and the engine, now with more displacement and better breathing, exhaled with the same fan howl that had become a signature. Then the 996 arrived with water jackets and different eyes.

Emissions and noise rules had shifted the frame of the conversation. Purists kept their postcards; engineers kept their calculators. Some things changed—the note of the exhaust, the arc of the headlights—and some didn’t. The engine stayed behind the axle, the front trunk still swallowed improbable luggage, and the car kept shrinking big roads into manageable questions.

In endurance, the 911 lineage watched a mid-engined 911 GT1 win Le Mans outright in 1998, and the stout architecture of its engine echoed in the GT3s that followed. Track days had once been the realm of trailers and earplugs. Around the turn of the millennium, they started to look like Saturday plans. The GT3 arrived with firmer bushings, taller redlines, and seats that assumed intent.

It lapped the Nordschleife fast enough to turn a test track into a marketing line, but the work behind the number was less dramatic: better brakes, stiffer shells, a chassis that sent clean messages. Over time the family expanded—GT3 RS cars arrived with wilder aero and narrower ambitions, Turbos learned subtler boost control and all-weather manners, and a 911 R briefly put a manual back beneath the fingers of people who had sworn their vow to three pedals. Generations named 997, 991, and 992 adjusted spring rates and wheelbases, added rear-axle steering and adaptive dampers, and quietly made sure the engine cooling and crash structures answered the present day without abandoning that shape. Even the 992’s transmission tunnel was packaged for hybridization years before the first road-going 911 with hybrid assistance was announced, an admission that the future would arrive on its own timeline.

The car’s public life has always run in parallel with private ones. You can find the 911 lined up outside bakeries before dawn, the rear lid ticking as it sheds heat into cold air. You can find it on alpine passes, where slow traffic becomes a puzzle to be solved with sightlines and patience rather than power alone. You can find it on used-car lots with mismatched tires and a stack of maintenance records, and parked under covers in garages where it shares space with bicycles and boats.

It is a machine people learn, not just own, and the learning persists: how to use the rear weight to rotate, how to manage trail-braking without waking the tail, how to blend daily errands with a willingness to drive the long way home. In the bigger story of cars, the 911 stands slightly apart because it refuses to graduate from its first principles. Rear engine, two-plus-two seating, the persistent question of how to move weight and air where they want to go without wasting either. Regulations have changed its bumpers and its cooling, competition has tightened its tolerances, and customers have demanded connectivity and comfort that would have sounded like science fiction in 1963.

Yet a line drawn in the air remains. It still looks like a 911 when you catch it at the edge of your vision, whether wearing a ducktail, a whale tail, or plastic covers over tires that make dirt look like an invitation. As synthetic fuels find pilot plants in harsh winds and hybrid systems slip into the drivetrain like a new thread, the car keeps threading the needle between machine and memory. It has never been the fastest way around every lap or the most rational answer to every spreadsheet.

It doesn’t need to be. The 911’s influence is not only in the trophies it has accumulated, but in the way it has taught generations that evolution can be patient and unapologetic. If the future asks it to become quieter and cleaner—and it already has—the silhouette will likely continue, bending with the times without breaking faith with itself. Somewhere between a morning commute and a midnight stage, it will keep drawing that line, and we will keep recognizing it.