CHAPTER 4 - The Grove That Drank the Sea

After accepting a vow to honor the Covenant, Barbra follows Saba and the wary boy Adem to a fog-drinking grove on Socotra’s Homhil plateau, where dragon’s blood trees collect sea mists. Using her blue glass shard and newly found palm-leaf diagrams, she realizes the trident-spiral is a wind compass, not a sea emblem. A resin-hidden shell mouthpiece at the grove seems to bend the chord west toward Detwah Lagoon, and Barbra, moving alone, uncovers a coral medallion marked with wave tallies. She tries to use it to open a blowhole’s song, but the tide rises and nothing answers; Saba later reveals the medallion is a decoy placed to mislead the impatient. Told to start over with the original coin and vial of resin, Barbra retunes her shard, listening for softer tones and mapping them to drum rhythms from Hadibu. The pattern points inland, toward the fog-rich cliffs of Momi rather than the sea. As dusk falls, she finds an ancient stringless wind-harp sealed into a living tree, only for a hidden line to be cut and the frame to swing out over a drop, leaving her fate suspended.

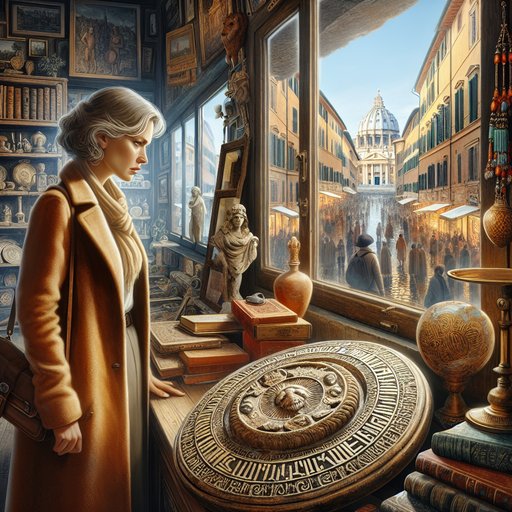

Barbra held the goatskin satchel to her chest as the woman with the trident-spiral ring waited, the plateau air cool and smelling faintly of resin. Her red hair lifted in the breeze, freckles stark in the diffuse light she always dreaded, yet her green eyes were steady as she nodded. Tight jeans, scuffed blue-and-white Asics, and a black leather jacket over a sun-faded tank—she felt more herself in this armor than in any makeup she hardly bothered with. “If I vow to honor the Covenant, you’ll show me the grove that drinks the sea?” she asked, aware of the wary boy watching the blue shard in her pocket.

Raised by grandparents after a wrecked night of sirens, Barbra had learned that oaths were the only bridges people could trust. Saba, the woman finally offered, lifted a hand for silence and then for assent. “You will not take, only listen,” she said, and set off along the ridgeline, the boy—Adem—padding in worn sandals beside them. They descended into a fold where dragon’s blood trees stood like parasols, their umbrella crowns catching cloud-scrap that blew up from the sea far below.

At each trunk’s base, limestone bowls cupped clear water beading from leaf tips, proof that trees did, indeed, drink the sea. The distant surf pressed its hush into the grove until every drop sounded like a tiny bell. At the grove’s heart sat a low stone plinth punctured by pinholes, their lips glossy with old resin, and Saba nodded for Barbra to try. She pressed her blue shard into a cluster of holes; the wind that fingered the grove became a long humming chord, and the glass lit the air with a faint indigo sheen.

She spread the palm-leaf diagrams, their trident-spiral etched in meticulous loops; the tone rose and fell over the lines like a bow over strings. The spiral was not for seas but for winds, a compass by pressure and pitch rather than by stars. Adem watched from the shade, one knuckle in his mouth, as if history might bite. A smear of resin tucked beneath the plinth’s lip had cracked with age, making a whisper line.

Barbra worked the plug free with her coin; Saba did not stop her, only lowered her gaze as if permitting a test to run. Inside lay a small shell mouthpiece, its rim incised with the same trident-spiral and a ring of nine dots like the sandbars of Detwah Lagoon. When she slotted the mouthpiece to the shard and blew, the grove’s chord bent until it leaned west, toward the lagoon and the open sea. “Detwah’s Gate,” she murmured, a thrill rising, and Saba’s ring clicked once against her walking stick.

She set off alone while the light still had a pearly fringe, the lagoon an impossible bowl of turquoise where fishermen turned their faces away when she waved. She shrugged on a floral denim jacket against the wind and climbed a buckled outcrop seam-welded with bottle glass whose embedded throats sang when the gusts came right. The shell mouthpiece called a deeper note from the stone; under it a soft hollow answered, and a resin smear flaked open to a shallow niche that smelled of incense and brine. Inside lay a coral medallion scored with the trident-spiral and a stack of wave marks, and she fitted it into a natural slot between fused bottles to await the aligning wind.

The air paused like a throat before a cough, tide crept around her ankles, the chord shattered into bickering throats, and nothing happened but the steady rise of water. She tried turning the medallion so the wave marks faced different horizons, listening for a grace note that would point her on. Her careful breath dissolved into ragged sounds as the sea climbed the rock, and a shadow moved up the dune, watching, then turning away. The old stiffness returned—the one that said do it yourself or not at all—a leftover from being four and taught to survive the silence after sirens.

Angry at being toyed with by ghosts and codes, she waded back through rising water, medallion clutched like a coin from a rigged game. The insight she had prized was pointing her astray. Saba waited where the sand hardened to road, Adem at her side, both grave in a way that did not feel victorious. “The coral is for outsiders,” Saba said before Barbra could speak.

“It was placed generations ago to feed the greedy with enough pattern to drown in clarity; the Covenant confuses those who rush, because a harp for rain is a weapon in the wrong hands.” Heat rose under Barbra’s jacket as she realized her mistake, and she nodded once, hard, as if to anchor herself. “The wind exacts a price,” Saba added, not unkindly, “and the first of it is patience.”

“Start again,” Saba said, gentler now, and tapped the vial of resin in Barbra’s pocket. “Begin with what you were given at your door—coin and resin—and do not reach for the glass until the wind asks for it.” Saba let her keep the false medallion, not as spoils but as a reminder, and the weight of it in her palm felt like a promise to be better. Back in her whitewashed rental in Hadibu, she spread everything on the floor—the copper coin, the blue shard, the goatskin satchel with its palm-leaf maps, and the vial that smelled like old tears.

She built a small spirit stove and melted the resin until it flowed like honey. She tested pitches the way her teacher had taught syllables, counting beats on her knuckles, letting the room’s white walls answer like a shallow cave. The shard, skinned with resin, sang in velvet instead of glass; she tuned its edge by rotating it over her notebook sketch until intervals settled. She held the copper coin over the diagrams and noticed how its worn markings nested into the spiral’s turns, notches pairing with rests in the drum pattern still walking her pulse.

It was meticulous, solitary work, the kind she had been built for by years of quiet, and for once she did not hurry. When the tone finally leaned, it leaned away from surf toward the pale cliffs that drank fog like wine. She brushed a thin veil of warm resin over pinholes she’d sketched from the Homhil plinth, then over the shard, letting it skin to a membrane. Set against the open window, the evening wind sent a subdued tone that pulsed in a beat pattern she remembered from rooftop drums—long, short, short, rest.

Aligning the coin’s markings with those intervals, she saw the trident-spiral resolve into a direction not seaward but inland, toward the higher limestone of Momi where fog hung like a second ground. Dawn found her already laced into her Asics, jacket exchanged for a lighter denim one flecked with glitter she rarely admitted loving, the coin and vial in her pocket. She walked until the path ran out and then kept walking, calves burning, breath steady as a metronome. The land rose to a white cliff lip as evening slid in again, the Arabian Sea a sheet of hammered pewter far below and the air brittle with the smell of stone.

Dragon’s blood trees leaned into a wind that did not want to speak, and tucked in the hollow of a trunk she saw it: an old frame of wood and bone and resin, a harp without strings sealed into living wood. She reached up, fingers trembling with the tremor of a start-over done right, when a hiss cut the air behind her, crisp as a blade through reeds. “Barbra,” someone said sharply, and a taut line she hadn’t seen snapped; the frame swung out over the drop as the ledge crumbled under her sneaker. Was the Covenant still testing her, or had someone else come to sever her last, best thread?