CHAPTER 2 - Whispers at Qalansiyah’s Blowhole

At the fissure revealed by low tide, Barbra turns to find a wary Socotri boy who knows her name but refuses to help, warning that families are watching. Following his oblique hint westward, she treks toward Qalansiyah, past dragon’s blood trees leaning toward the surf. Fishermen and market women bluntly refuse her questions about the Dragon’s Blood Covenant, and a boatman refuses to take her to the singing sea cave. Going alone at the ebb, she slips into a breathy chamber where melt-glass bottles fused into rock hum with the wind, and she discovers a blue shard etched with a trident-spiral that seems to echo the markings on her copper coin. The find is a first, tangible clue, but it gives her no next step; the pattern is unreadable, the chamber’s acoustics confusing, and the locals’ silence impenetrable. Voices echo outside the cave and a stone scrapes over the entrance as the blowhole’s song falls sharply quiet, leaving her in damp dark with only the shard and the resin’s perfume. As water begins to push through clefts and the wind shifts to a troubled moan, she hears someone speak her name again and debate whether to leave her there to learn patience, and she wonders who is holding the key to the Covenant—and whether they will force her to turn back—or trap her.

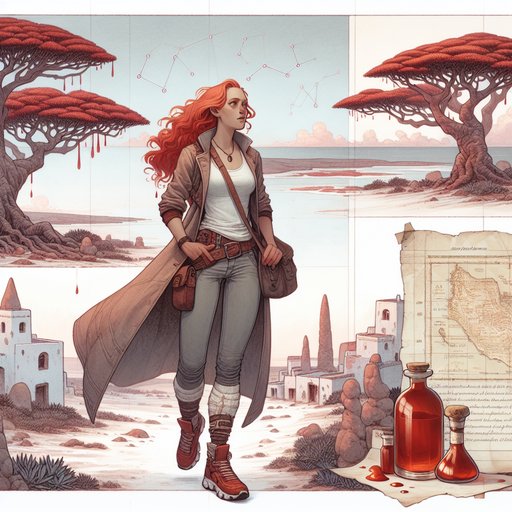

Barbra froze at the edge of the fissure, the tidal breath of the cave washing cool against her shins. The voice that had spoken her name was young and cautious, shaped by salt air and a language older than the airport signs. She spun, red hair flaring like a struck match, freckles she despised sharpened by the low overcast light. A boy stood on the rocks barefoot, a rolled scarf at his neck, eyes the color of wet basalt and a net slung over one shoulder.

He took a step back when she smiled, as if kindness were a trick he had been warned about. “You shouldn’t be here,” he said in careful English, glancing at her blue and white Asics as though they might betray her to the stone. “Not alone.” The wind dragged his words long, and he flinched as a gust curled through the bottles wedged in the cliff face and drew out a hollow note. “They see everything.

The families.” The last word landed like a pebble dropped into a well. “I’m just looking,” she answered, the truth as disarming as she could make it, standing there in tight jeans and a white tank, a floral denim jacket unbuttoned against the humidity. She had learned to be alone and make her own decisions before she knew what the word guardian meant, but she kept that to herself. “Look where the trees drink the sea,” she added softly, testing the riddle that had been left with the coin.

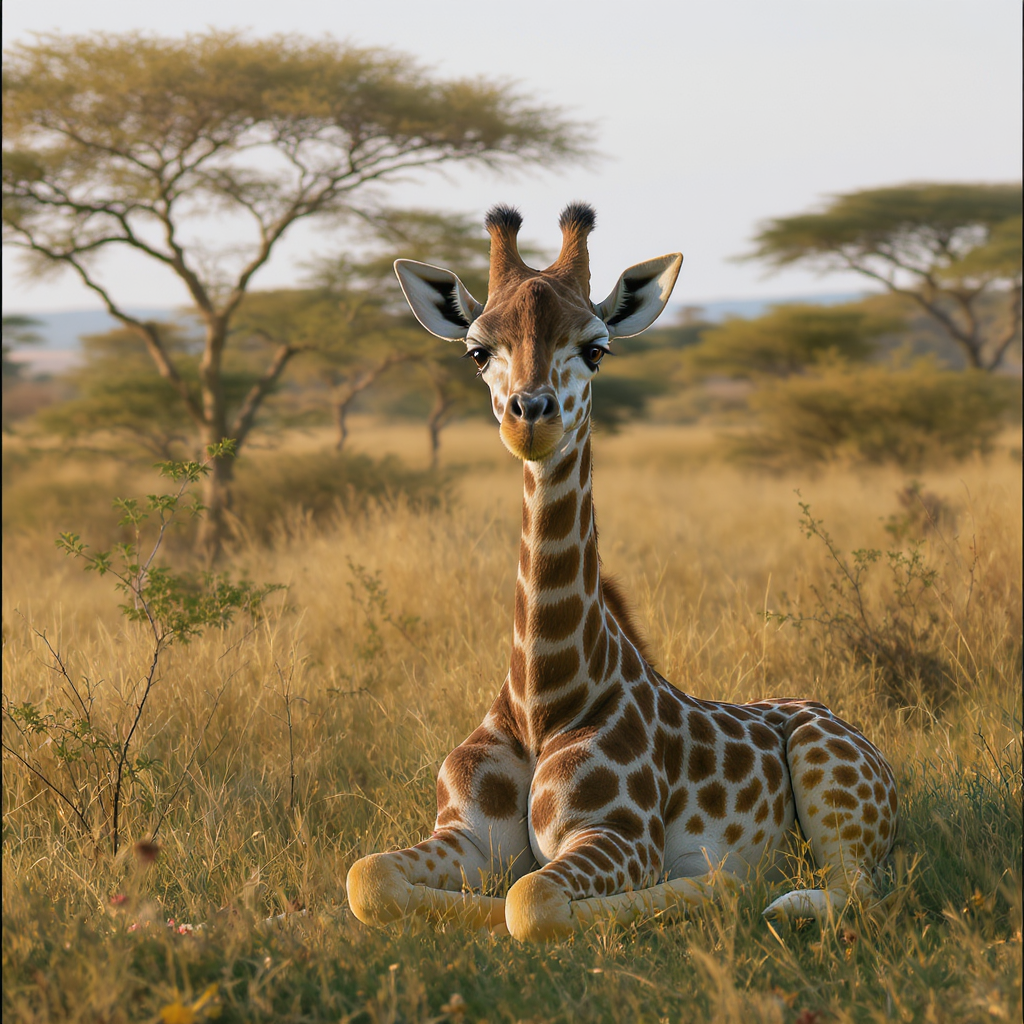

The boy’s eyes flickered; recognition, quickly covered by a frown. He pointed west, toward the honeyed glow of Qalansiyah’s bay, and then he darted away, scrambling up a goat path until he was a smear on the white stone. She walked for hours, skirting coves cut from chalk and basalt, the island’s famous dragon’s blood trees leaning like candelabra toward the surf. The wind smelled of resin and salt and something ferrous, a scent like old blood scabbed under whitewash.

Her muscles loved the uneven ground; the long walks of her life had given her a rhythm that steadied the mind while the world showed its secrets one rock at a time. When the heat swelled, she shrugged out of her jacket and tied it at her waist, letting her shoulders breathe, freckles brightening despite the cloud cover. The last of the outgoing tide licked at her shoes, the foam tracing small hieroglyphs around her feet and erasing them before she could read a single one. Qalansiyah opened like a story she couldn’t quite tell—boats drawn up like sleeping animals, nets hanging in soft black curves, women in bright scarves carrying baskets of spiky greens.

She asked a boatman with a face carved by sun if he would take her to the blowhole, and his mouth folded into a line as fine as a fishing wire. “No boats,” he said, offering her a cigarette he did not light himself. An older woman at a stall selling honey from dragon’s blood resin shook her head when Barbra mentioned singing caves, and with a tender, pitying glance turned to rearrange jars as if the labels might arrange fate itself. The word covenant traveled from mouth to ear and back again in the low market murmur, and where it landed, doors shut and eyes looked at anything but her.

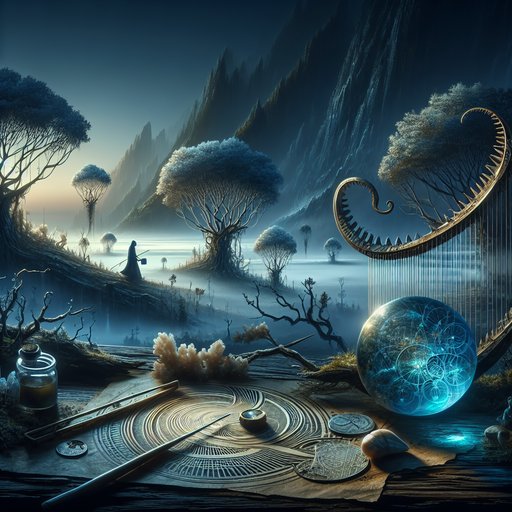

She was born without the need of anyone’s permission, so she went alone at the turn of the tide, following a path of goat prints toward a lip of stone where the cliffs were hollowed like a lung. The blowhole breathed, long and slow, each exhalation pulling a sigh from the embedded bottles that someone, seasons ago, had pushed into crevices. The song of glass on wind was low and eerie, a sound that lived in her sternum more than in her ears, and it nudged her forward. A darker seam in the rock widened to a shoulder’s width, and with a hand against cold stone, she slid sideways into a narrow entrance that tasted of salt and iron.

The ceiling grazed her hair; the passage opened; her breath echoed ahead of her like a second self. The chamber beyond was taller than she expected, not a cathedral but a forgotten chapel, with glass fused into the walls at irregular intervals, like organ pipes set by a drunk god. Light bled down through small chimneys in the rock, open to sky, and the wind tongued them like flutes. In the seeping wall, dragon’s blood resin had dripped and hardened, its glossy tears smelling faintly medicinal, and the scent made her think of pharmacies and ferry decks.

She took the copper coin from her pocket and held it up to a pattern scratched into a ledge—a trident sprouting into a spiral—and her breath snagged when a curve matched a mark on the coin’s edge. A tremor of triumph followed by the flattening realization that beyond the matching edge was nothing she could read, no sequence that told her where to go next. She brushed the ledge with her fingers; the grooves were shallow, worn by time and spray. A sliver of glass, blue as deep water, caught under her nail, and when she teased it free, she saw lines engraved into it—delicate hatches in a shy geometry.

It was beautiful and cool against her palm, the weight meaningless and yet thrilling, as if she held a piece of someone else’s thought. She worked the shard into a pocket in her jeans and took out her phone to photograph the wall, but the wind’s song swelled, and her screen shivered with salt damp. The first clue was there in her hand and on that ledge, and it asked a question instead of answering one. A wave pushed into the chamber from a seam near her ankles and retreated with a rude hiss, and she imagined her glass cabinet at home waiting for a new story that wasn’t ready to be told.

She swallowed impatience and closed her eyes, listening to the notes the wind drew from the chimneys, trying to hear pattern rather than weather. The spell broke with a scrape from outside, stone on stone, soft, as if whoever moved it feared a shout would carry. She stilled, then stepped toward the entrance, but the song shifted, flattened, and fell to a discordant murmur that made her teeth ache. The cave grew a shade dimmer, and she could not tell if the change was light or the humility that comes when a door closes in your face.

She squeezed sideways toward daylight, face brushing cool rock, and saw the boy again—a flash of scarf, a net, a quick glance over his shoulder. He met her eyes and shook his head, not in cruelty but in some calculus of caution and duty they were both too young for. “Go,” he hissed, and backed away as two older men approached along the path, their steps slow, their clothes wet to the knee. She stepped out as if she were just another tidepool tourist and offered a hello in Arabic; one man returned it, his expression respectful but closed, the other didn’t look at her at all.

When she asked about the blowhole, they gestured around them with open hands, like men showing a river and pretending not to know its source. By the time they were gone, the urge to chase the boy and demand help had burned down to coals. She turned back into the cave, stubbornness the flint that kept her going when logic suggested most people would wait for a guide. The passages were narrower on this return, somehow, or that was her mind playing tricks—she was careful with her steps, her Asics squeaking faintly on wet limestone.

She pressed deeper to a second chamber where the air seemed older, the resin smell heavier, a sweetness like incense that had turned in the bowl. The wind at the chimneys shifted again, brushing a new note—a minor key that slid under the skin. The surge came without warning, a bulging push of water up through some siphon in the rock, a cold slap at her calves that left grit and pebbles around her ankles. A stone ground against stone near the entrance again, louder now, then thudded; she spun, heart in her throat, and saw the light from the first chamber collapse to a thin ribbon along the floor.

She darted forward, shoulder to rock, testing the gap, and felt it resist with the stubbornness of something wedged by hands that knew these dimensions better than she did. Another wave nosed in and pulled back, taking warmth with it; she stared up at the chimneys, too skinny for anything but wind and the occasional curious crab. Her freckles prickled as if each one were a cautionary mote, and she laughed once, short, the sound unlatching the silence so the cave could swallow it whole. Outside, men’s voices braided with the sea, low and threaded with words she couldn’t catch, then her name, distinct and soft, as if it were an offering.

“Let her learn,” someone said, the Arabic clear enough for her to understand, and another voice answered, skeptical, then sighed like the wind itself. The blowhole’s song thinned to a breath, and the glass in the walls stopped humming, leaving her ears ringing in the new quiet. She touched the blue shard through the denim of her pocket and felt the coin beside it, useless as a key without a door. Was I meant to wait, or to fight, and who had decided to lock the world’s oldest instrument away from me today?