CHAPTER 3 - Whispers on the Black Water

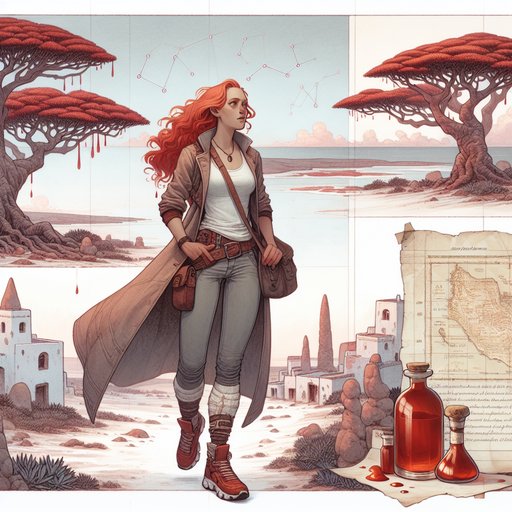

After being forced back from the private maritime club by an injunction, Juan senses he’s being tailed and that his phone is tapped. Seeking clarity, he escapes the city on his vintage Moto Guzzi for a solitary night ride to the Albufera wetlands. There, on a wooden footbridge, he meets an old fisherman who once knew Juan’s father. The man tells an unsettling anecdote about nocturnal gatherings he calls “bat nights,” when men in suits arrived by van with crates labeled as donations, masking diesel with orange oil, and paying with bronze-and-enamel tokens bearing Valencia’s bat. He swears he saw Blanca Ferrán meet a silver-haired man at the canal and describes esparto fibers and salt flecks on another man’s clothes. From under a mooring cleat, he retrieves a damp receipt tied to those tokens, marked Token 7B and “Almacén 14-1,” pointing Juan toward a specific port warehouse. As headlights appear and a taunting call proves his phone is compromised, Juan discovers a GPS tracker hidden on his bike. Men linked to the club try to box him in near the reeds. He escapes down a narrow dyke, clutching the new clue, only to be cornered again as a projectile thuds into a post and a voice demands what he will trade for the token, leaving the night vibrating with menace.

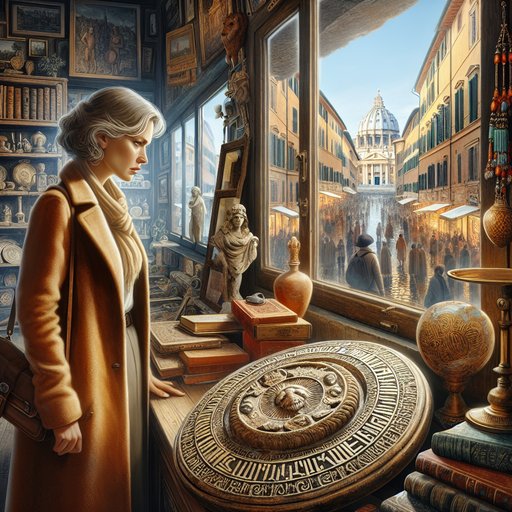

The injunction had the oily sheen of inevitability, the kind of legal varnish that turned facts into furniture. By the time Juan left the portside office, the night had come down like a shutter, and a dark sedan had taken up station a car length back, its headlights polite, its presence unmistakable. His mobile hissed with a high, insectile whine whenever a call connected, and text threads rearranged themselves like skittish anchovies. He pocketed the bronze-and-enamel bat token and the Saint Michael medallion, shrugged into his weathered leather jacket, and wheeled the Moto Guzzi into the sodium glare as if stepping onto a stage he despised.

He led his watchers in lazy loops through Nazaret and around the fish market, feinting left toward the Real Club Náutico before cutting through side streets where citrus crates perfumed the air. In his mirror the same shadow kept its patient distance: a gray Seat with one fog light slightly dimmer, a mole in the city’s face. He dialed the retired sergeant out of habit, then killed the call at the first click before the man could answer, certain someone else was listening. At the roundabout he took the El Saler road, the Guzzi’s engine a low thrum that steadied the pulse in his throat.

The Albufera spread before him like a dark pupil, taking in the sky’s star-prick glare and the port’s distant orange bruise. Reeds scratched at the night with a papery whisper, and frogs stitched a pulse line under the breeze that carried salt and mud and a sweet, fermenting note from drying rice. He parked by a wooden footbridge near El Palmar, killed the engine, and let the silence fold over the last of the city’s noise. The token felt heavier than metal in his pocket, as if the emblem on its face had its own gravity.

Footboards creaked as he walked, boots careful over weathered slats, each knot and nail a tiny wound gone silver. Juan leaned on the rail and watched a skiff bump softly against a mooring post, its painter rope creaking in a tired rhythm. He reached into his jacket and thumbed the medallion’s worn edge, thinking of his brother and the brittle sentence that had divided his family into the before and the after. A figure detached from the reeds, a short man in a flat cap with a face burnished to brown leather and hands corded like mooring lines.

“Inspector,” the man said, not really a question, voice pitched to carry without breaking the lake’s skin. “I knew your father. He fixed my outboard when everyone else said to throw it to the eels.” His eyes flicked to Juan’s pocket. “You carry a saint and a bat; that’s a mix.” He introduced himself as Tonet, though the name sat like a card folded into a hatband, seldom used.

Tonet talked about nights he called “bat nights,” when no moon glared and high men came low, their vans backing to a boathouse shutter while diesel hawked in the throats of small launches. The air then was sharp with orange oil, so much of it the frogs went quiet, a citric veil over tar and old rope. “They paid with coins, not euros,” Tonet said, making a circle with thumb and forefinger. “Bronze with enamel.

A locker key that buys silence.” He watched Juan’s face the way old men read tides. He had seen a young woman three nights before, nervous in a linen jacket at the Gola de Pujol footbridge, clutching rolled tubes as if they were oars. “Pretty eyes, tired, the way teachers look in June,” he added, and Juan felt the description land. A silver-haired man in a neat blazer met her, furious without raising his voice, and two other men stood back with arms roped in salt scurf as if cuffed by dried spray.

When the woman turned away, something dropped into the reeds with a plop that was not a frog. Tonet bent, lifted a plank from the bridge edge to reveal a dark crevice, and pulled free a damp slip of paper tied with a twist of esparto. “They leave things under wood. Letters for the lake,” he said.

He handed it to Juan: a water-warped receipt embossed with a bat over an anchor, “Círculo Marítimo de Valencia – Convivium,” stamped 7B, and in purple pencil: Almacén 14-1, 23:30. The serial pricked Juan’s memory of the faint mark on the token’s rim; they fit like teeth. “Once,” Tonet went on, voice lower now, “I told a ranger what I saw. Next week, he was counting birds in Teruel.

Another boy told me he was paid to unload crates labeled ‘donativos.’ When he refused, he turned up two days later white as winter, foam on his lips.” The word overdose was there without being touched, a bruise under a sleeve. Juan felt the medallion heat in his palm, the way metal takes warmth and keeps it a second longer than the skin. Juan’s phone vibrated in his jacket, unknown number, and against his better judgment he answered, as if pulling a splinter to admire its barb. “Enjoying the wetlands, Inspector Ovieda?” The voice was smooth as an eel in silt, unplaceable, filtered.

A distant engine idled on the causeway; light swept the reeds like a bored searcher. He thumbed the phone dark without replying, slid it inside his boot, and watched Tonet’s face tighten. Back at the bike, under the seat he found what he had missed in his haste: a little black box the size of a sardine tin, magneted to the frame with a red LED blinking like a steady, stupid heart. He wrapped it in foil from an old emergency blanket in his kit and pocketed it; whoever was counting his steps could count the wrong ones.

The lake took a breath and let it out, a sigh that shifted the reeds so their dry applause shivered down the line. Somewhere, a rope slapped wood the way a palm slaps a table to quiet a room. A white van nosed onto the packed dirt like a whale beaching itself, followed by a dark sedan whose cabin light stayed ominously off. The club guard Juan had seen at the basement grate stepped out, his jacket flecked with tidelines of salt like fossil milk, sleeves brushed with esparto fibers that sparkled pale.

“Inspector,” he said with a smile that let no teeth show, “our members value privacy.” Two other shapes fanned toward the footbridge, their boots gentle, as if not to wake something that slept here. The Moto Guzzi screamed into life on the first kick, a snarl that reached down his spine with relief and something like joy. He slid past the van’s bumper with a hand-width to spare and took the dyke path, reeds lashing his legs as dragonflies ricocheted off the headlamp like sparks. The lake’s edge tunneled toward him, black and silver, the world summarized into gravel crunch, wind, and the quick glance of stars in water.

He didn’t look back until he had to, when the sedan’s headlights carved the path white. He cut the engine and ducked into the shadow of a tamarisk, breath steady, hands sure in the dark, the receipt open in one palm. Almacén 14-1 breathed up at him from a warped page, the bat-and-anchor seal smeared but definite, Token 7B underscored like an accusation. Across the water a light winked and reappeared, not a fisherman’s headlamp but the slow blink of a bearing.

Something hissed and thudded into the post by his ear, splinters nicking his cheek, the smell of cordite braided into orange and mud. “Trade time,” a voice called, on the other side of the reeds, amused in a way that had nothing to do with humor. “What will you give us for the little coin, Ovieda—your silence, or your breath?”