CHAPTER 3 - Echoes at the Wrong Tide

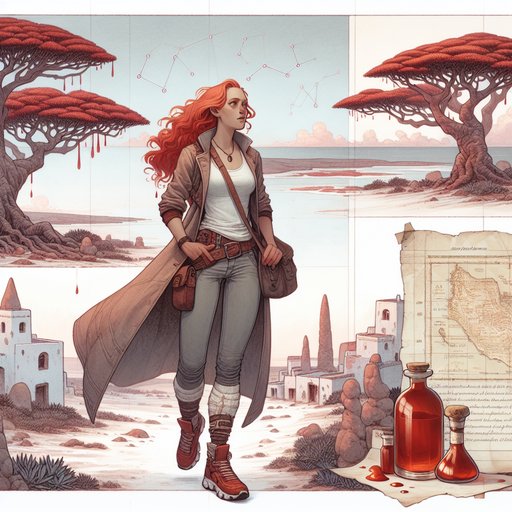

Barbra’s attempts to decode the whale-bone token and the breathing cleft stall, the basalt’s warmth gone and the locals sealed tight. Seeking a break, she dresses for a night out—jeans, low-back tank, glitter jacket, and carefully guarded Louboutins—and drives to Tórshavn. In a harbor bar she meets Runa, a fiddler who recognizes the sigil and reveals the riddle points to echoes and spring tides: count seven breaths from the fifth echo near the north lip of the lagoon, and beware the old families who guard the gates. Back in Saksun before dawn, Barbra tries the echo-count but slips on the sequence. Hiking higher to clear her mind, she notices a sheep’s bell etched with the sigil; aligning the bell, token, and sunstone casts an arrow of light with seven pricks pointing to a notch on the northern ridge. The basalt’s song tightens to a wire, a pale arch of spray marks a seam, and the shadowy woman reappears and vanishes. Warm breath rises underfoot, leaving Barbra on the brink of the window’s opening and the families’ scrutiny.

Morning leaked into the turf-roofed cottage as a thin, pewter light, and the note with the sigil still lay on the table: Not yet. Wrong tide. The whale-bone token felt like a sliver of winter between Barbra’s fingers, smooth and stubborn, its etched lines refusing to meet any notch or draft she mapped. She pressed it to the cleft’s rubbing, angled it toward the window, even held it to her ear as if it might whisper.

The basalt’s low song was faint, a memory rather than a voice. Freckles flushed across her nose as frustration warmed her face, and she hated that she noticed them. All morning she chased sterile possibilities. She rubbed graphite over carvings until her fingertips gleamed, measured drafts inside the cleft at different hours, and held the calcite sunstone to the mist to coax its pale band.

Breezes came and went, but the cleft had stopped exhaling; the little breath of warmth she’d first felt was gone as if the island itself had pursed its lips. The boathouse doors stayed shut, and the shadowy woman did not return to the ridge. Dead end, she admitted, a phrase she’d never liked because it meant waiting on someone else’s schedule instead of her own. She snapped the notebook shut.

If the island wanted patience, she would steal some joy from it first. She changed out of her trail-dust, sliding into tight jeans that knew her shape and a black tank top with a low back that bared the two little dents at her spine, a feature she wasn’t shy about. From her travel rack she chose the glitter jacket she almost never wore, all night-sky flecks and soft lining. She glanced at her Asics, then at the Louboutins in their cloth bags; she hardly brought them this far north, but for a night in Tórshavn she’d risk the careful click of their red soles.

Tórshavn was a warmer world of lamplight and windows fogged by laughter. A bar by the harbor spilled fiddle and drum onto the wet boards, and the room smelled of rope, coffee, and raincoats drying over the backs of chairs. Barbra ordered a beer and stood for a while, just letting the hum pass through her until her shoulders unknotted. A fiddler with sea-salt hair and a half smile introduced herself as Runa between tunes, her accent lilting like the water against the quay.

They traded small talk about cliffs and weather, and Barbra felt that old, dangerous ease of liking someone too fast and not minding the bruise that might follow. When the tempo lifted, Runa pulled her onto the floor with a wink. Barbra’s Louboutins clicked like castanets against the scuffed boards, and her long walks paid off in light steps that found the beat without effort. For the length of a reel she forgot the cave, forgot the note, forgot even the scatter of freckles she always tried to ignore as eyes found her hair in the swinging light.

At the bar to pay, she fished for a coin and the whale-bone token slid halfway into view. Runa’s glance snagged and held, her bow hand stalling midair as if a string had snapped inside her. They stepped into the chilly air beside the quay, the music muffled, fog unraveling from the water in soft ropes. Runa didn’t touch the token; she only traced the sigil in the air a finger’s breadth above it, eyes narrowed.

Not yet, she murmured, almost to herself, wrong tide—an old phrase from my grandmother. She led Barbra four posts down to a rusted bollard and showed her a matching mark carved into iron, the same curls and cross, but with a tiny extra notch like a tick at the edge of a compass. That notch, Runa said, is how we count where the sound begins. It isn’t steps, Runa explained, it’s echoes.

The stone chambers breathe and sing; count seven from the fifth means you wait for the fifth echo after the first surge and then mark seven more breaths, and only then do you listen for the door. Neaps won’t do it. You need the spring, and the spring is coming tomorrow night on this coast, near the north lip of your pretty little lagoon. If you go, you won’t be alone; old families watch the gates, and some have longer memories than good tempers, she added, sliding a folded paper into Barbra’s hand marked only with a hymn number: 129, v.5.

When the bar emptied, they didn’t make promises. Barbra drove the switchbacks back toward Saksun in the damp dark, changing from her heels to her Asics in the passenger seat before the road turned to sheep tracks. In the cottage she cleaned the Louboutins, set them back in their bags like small sleeping animals, and watched her own reflection in the window until it blurred into black. Her grandparents had taught her patience by making her mend nets and wait on bread to rise; she could do it now if the island required it.

Still, as she clicked off the lamp, a small thought nagged—what if Runa had been warning her away, not guiding her? Dawn came too soon and too clean. Barbra laced her Asics, shrugged into a floral denim jacket instead of glitter, and took the token, the hymn note, and the sunstone up the sheep paths above the lagoon. Wind lifted her hair and she tasted salt on every breath.

She tried Runa’s echoes, humming and letting the basalt answer, counting the faint rebounds inside the cliffs—one, two, three, four, five—and then seven more, but somewhere the sequence slipped like wet rope through her hands. She grinned at her own stubbornness and then scowled; the door remained only a rumor of warmer air against her wrists. She climbed higher to a high, saucered tarn scattered with reeds and gray feathers. A sheep with a torn ear drank at the edge, its bell giving a tired clink that felt accidental until the wind steadied and a clean interval rang so true it vibrated in her sternum.

The bell was old brass and crudely scratched with the same sigil, and someone had drilled a tiny hole through one arm of the cross. Barbra held the token behind it and the sunstone to the side, and light ran through bone and brass to cast a small, precise geometry on the grass. An arrow resolved, with seven pricks marching away from a larger puncture, all pointing to a dark notch on the northern ridge. She lined the arrow’s point with the notch, and at that angle the basalt’s song gathered to a single thread, thin as wire between her ribs.

Across the lagoon’s lip a seam in the cliff drank the morning light and gave it back as a pale arch of spray. On the opposite rise the woman from the ridge appeared, raised her palm in warning or welcome, then slipped into the fog. Warmth rose from the ground under Barbra’s soles, a soft exhale she felt through rubber and skin. Was this the breath window Runa had named—and would the families let her step through it before the tide turned?