CHAPTER 2 - The Bone Token and the Breath of the Basalt

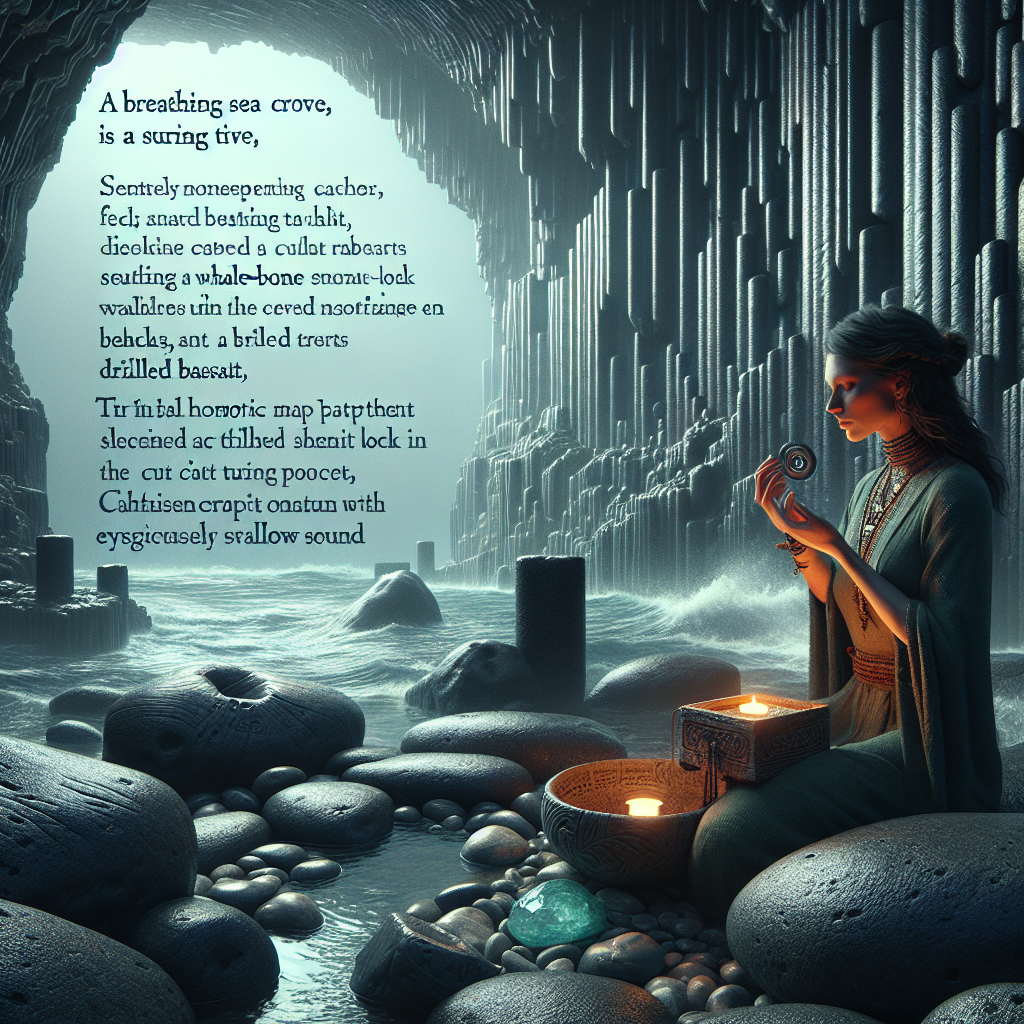

At dawn in Saksun, Barbra returns to the cleft that exhales warm air, following the cryptic hint to "count seven from the fifth" while using her calcite sunstone to read the mist. Inside the basalt, she discovers her first concrete clue: a carved whale-bone token etched with a sigil. Despite careful attempts to align it with notches and winds, the token reveals nothing else. Seeking answers, she approaches guarded locals at a boathouse; they refuse to help, warning her off with tight-lipped caution born of old family vows. Back at her turf-roofed cottage, Barbra maps drafts, makes rubbings, and persists, but each experiment leads to a dead end. At dusk she slips back into the cleft, only to feel the tide turn and the stone offer no release. A shadowy woman watches her from the ridge, then vanishes, and when Barbra returns home, she finds her door ajar and a note bearing the same sigil and a translated warning: “Not yet. Wrong tide.” The chapter ends with Barbra clutching the token as the basalt’s low song rises, uncertain who is guiding her path—or blocking it.

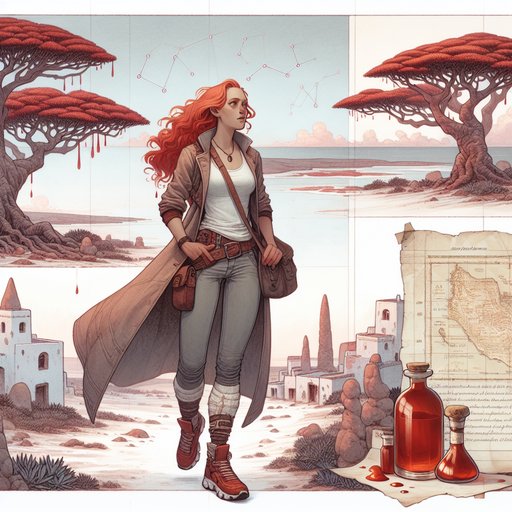

Morning in Saksun smelled of salt and sheep and damp peat, the air tender and raw on Barbra’s cheeks. She laced her blue and white Asics with a practiced tug, slid into tight jeans and a black tank top, then shrugged into a leather jacket scuffed from other roads. Her red hair was a loose braid down her back; the freckles she disliked seemed louder in the cold light, but she didn’t bother with makeup. She had slept lightly, listening for that organ-deep hum beneath the turf-roofed cottage, imagining it swelling with the tide like a bellows.

She carried the scrap of map that murmured, “count seven from the fifth,” and the calcite sunstone wrapped in a cotton handkerchief, tools for a day she already knew would refuse to bend easily. The lagoon lay milk-blue under a sky streaked with gulls, its floor a mirror of wet sand and dark stone at low tide. She picked her way along the edge, passing cairns that rose like careful sentences, their stones chosen by hand and intention. Counting aloud, she marked the fifth in the line by a fattish base rock, then walked to the seventh stepping stone beyond it, pausing to hold the sunstone to the sky.

A faint band swam across the crystal and shimmered toward the cliff face, exactly where the cleft breathed its soft warmth into her palms. The exhale against her fingers felt almost mammalian, as if the mountain itself were alive and sleeping lightly. She squeezed sideways into the cleft, shoulder to basalt, the leather jacket rasping against rock that was surprisingly smooth, like cooled tar. The floor pitched gently downward, and her breath fogged before her as if the warm draft were meeting a colder ghost.

A peculiar seam caught her eye: a hairline crack no wider than a thumbnail, set knee-high in the wall, with a triangle of lichen green as old coins. She ran her fingertips along it and felt a give, a softened edge deliberately worn. When she pried aside a pebble and nudged a buried shell, something loose clicked behind the stone and slid forward into her palm. It was a token of carved whale-bone, long and flat like a tongue depressor, polished satin-smooth by hands not hers.

A sigil had been etched into it: two offset circles bisected by a single vertical line, crossed faintly at the base by three short ticks. The bone smelled faintly of lanolin and salt, as if it had remembered the animal it once held upright. Turning it in the low light, she thought of the glass wall cabinet back home, shelves of remembered struggles and elations, each telling her she belonged in hard places. She set the token against a notch in the opposite wall, heart catching, but nothing yielded—no hiss, no grind, no secret breath of opening, only the steady warm draft and the deep, organ-thick hum somewhere below.

Back outside, the wind had roughened. The villagers were stirring in their tight cluster of buildings, smoke lifting from turf roofs in soft braids. Barbra headed for the boathouse where she had seen nets drying like green veils, and found an elderly man with weather-bleached eyebrows coiling rope while a woman picked at a tangled float line. “Excuse me,” she began, showing the edge of the whale-bone before she fully drew it out.

The man’s eyes flicked to the token and then to the woman; he tightened his coil so hard the rope creaked, and the woman’s fingers stilled. “We don’t talk about the Gates,” he said carefully, the r in “Gates” rolling as if he disliked the taste of it. Barbra kept her voice level, assertive without prying, the way she had learned to be since she was four and had stared up at her grandparents and understood the world could drop out from under you without warning. “I’m not here to plunder or publish,” she said.

“I take care—always.” The woman’s gaze slid away to the sea and back, softer, but she shook her head. “Not your tide,” she said, which felt like a dismissal and an omen in one. Barbra walked back up the hill past the church with the white walls and its tiny graveyard pressed into the earth as if the dead were still trying to keep warm. In the cottage, she laid out the bone token on the table beside the map scrap and a pencil, then began making rubbings of its sigil on thin paper.

She held the token against the map’s faint ink lines, trying to assign meaning to the circles and ticks: columns? breaths? the rhythm of the lagoon? She held the sunstone to the window, watching the band swing like a compass needle toward the cliff; then she moved the token in the draft by the door, mapping the flows with dampened fingers.

Nothing resolved, and the day grew heavier, the kind of stubborn stalemate that pressed on her patience and made her freckles feel hot on her face. Her grandparents had taught her how to wait—how to fix a fence in a wind, how to listen to old stories without interrupting the pauses that carried half the meaning. She took a breath and tied her hair up, grabbed a headlamp and a smaller, floral denim jacket in case the leather chafed too much in the narrow stone. By dusk the sky had fallen into colors of slate and bruised plum, and the lagoon’s sheen had dulled to a pewter plate.

She trod carefully along the path, muscles loose and ready from a lifetime of long walks, the Asics planted sure on slick stone and weed. This time, when she entered the cleft, the organ-note rose a fraction, deepened, and her ribs felt it the way one feels footsteps on an upstairs floor. Inside, the headlamp turned the basalt to wet glass edges, glittering here and there with feldspar sparks. She found three shallow notches at hip-height and fit the whale-bone token into each in turn, trying angles, counting the ticks in different orders, standing on the seventh stone from the fifth cairn like a ritual and holding her breath to the rhythm of the hum.

The token made contact with something hard and ancient and indifferent; it yielded the way a locked door yields to a polite knock—not at all. The tide shushed in the distance, that long hush that is also a warning, and the first cold lick of returning water brushed her heel. She retreated with reluctance and careful dignity, unwilling to scramble, unwilling to be chased out, yet rational enough to respect the ocean’s timetable. At the top of the path, she paused to look back, letting the cliff edge wind comb her thoughts.

A figure stood on the ridge beyond the church, still as a cairn, a woman with seal-dark hair and a scarf snapping like a pennant. Barbra lifted a hand in acknowledgment more than greeting; the woman did not reply, then slid out of sight with the grace of someone who knew every tussock and crease. Barbra followed along the ridge for twenty paces, found only sea thrift crushed into a new dark line and a whorl of footprints that dissolved into grass. Peat smoke threaded the air—close, too close for a village evening—and she suddenly wanted walls around her, not out of fear, exactly, but a tug of caution that felt rational and earned.

Her cottage door was ajar by the width of a palm. She was certain she had locked it; self-sufficiency had made neatness and vigilance her default, and the key had clicked under her thumb before she’d left. The room felt altered, subtly, like a chord had been removed from the air; the kettle sat on the hob where she’d left it, but a chair had been pulled three inches from the table. On the tabletop lay a folded scrap of parchment, rough-edged, its fibers swollen slightly with the damp breath of the day.

She unfolded it and saw the same sigil etched in ink as on the bone token, and beneath it four Faroese words she translated in her head with a shiver: Not yet. Wrong tide. She stood still and listened, the leather gone for the soft scrape of fabric as she shifted weight, the headlamp now dark, the cottage’s small windows banded in wind and the night’s first spit of rain. The bone token felt heavier than before, warmed by her grip as if it preferred living hands to stone.

Somewhere under the floor, or under the hill itself, the organ’s hum swelled and changed key, the way a singer finds a harmony that was always there, waiting. Someone else knew the rhythm of this place and had chosen not to share it, not yet. Who waited with her in the dark—ally or gatekeeper—and would the Basalt Gates open on their time, not hers?