CHAPTER 1 - The Song of the Basalt Gates

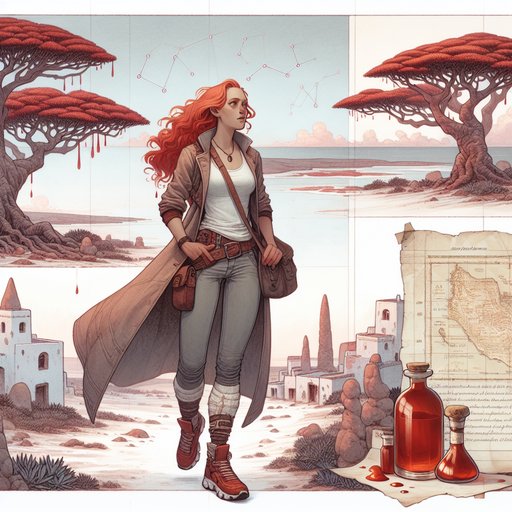

Barbra Dender, a 31-year-old red-haired traveler raised by her grandparents and known for bold, solitary quests, heads to the Faroe Islands for a new adventure. She rents a turf-roofed cottage above a tidal lagoon in the village of Saksun, unpacking her usual jeans, Asics, and a few cherished jackets while carefully stowing the Louboutins she rarely wears outside cities. Drawn to the stark cliffs and sea-caves, she hears a haunting resonance at low tide—an organ-like singing from the basalt—while noticing cairns arranged with uncanny care. A cautious local hints at an old secret known as the Basalt Gates, long protected by families who distrust curiosity, yet Barbra’s integrity wins her a cryptic clue. Late at night she retrieves a calcite “sunstone” from the sand and uses it to detect a faint directional band in the mist. By morning she receives a scrap of map that reads “count seven from the fifth,” leading her back to the lagoon, where she finds a concealed cleft that exhales warm air. The chapter ends as she realizes she may have found the entrance to a hidden labyrinth, wondering what sings beneath the rock.

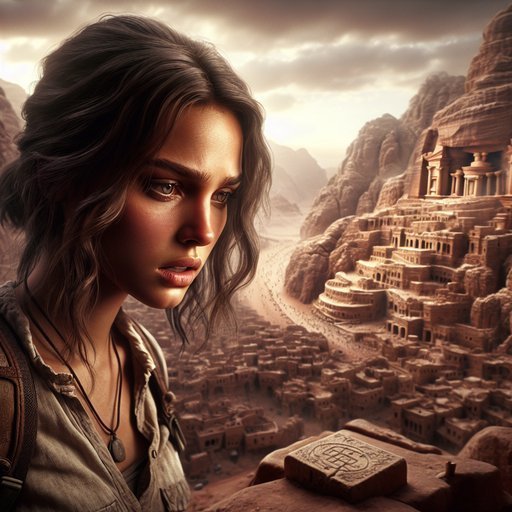

Barbra Dender chose the Faroe Islands for her next escape, a scatter of green humps and knife-edged cliffs where the North Atlantic never quite settles. At thirty-one, with red hair that flashed like a signal in gray weather and freckles she loathed as if they betrayed her, she traveled light and alone. She rarely bothered with makeup, having learned from years of field dust and hostel mirrors that she neither needed it nor had the patience for it. Long walks had made her slim and carved subtle strength into her calves and shoulders, the kind of muscle that came from moving for hours with a pack and a map.

She wanted a place few people visited, and on the map the Faroes looked like a whisper in the storm, exactly the kind of whisper she loved to follow. She rented a turf-roofed cottage perched above a tidal lagoon in the village of Saksun, a curve of water cupped by emerald slopes and basalt. The cottage was hunched and warm, smelling faintly of lanolin and old wood, with a low-beamed loft and a single small window that watched the tide breathe. A kettle sighed on the stove while wind stroked the roof with sound like distant hands on a drum.

When she opened the cupboard she found a chipped blue mug, a tin of tea, and a folded dishcloth embroidered with a puffin. On the wall, someone had hung a pair of worn oars, their handles polished by palms, as if the room itself remembered a journey. She unpacked in her usual order, sliding her tight jeans onto a chair and aligning her blue-and-white Asics by the door. A white tank top draped from a peg, and she unrolled two jackets—black leather with scuffed elbows and a floral denim thing that made strangers smile at her in airports.

Her many Louboutins pumps came out in their red-dusted bag only for a moment, their polished heels glinting like quiet trophies, before she tucked them back into tissue as if into a nest. She almost never wore them outside cities but carried them anyway, a habit of feeling prepared for the unexpected evening that might ask a different version of her to walk in. On the shelf above the bed, she placed a photograph of the glass cabinet at home, its shelves crowded with artifacts of past quests, and promised herself something on these islands would earn a place there. On her first morning she took the cliff path as if it were waiting for her, the grass slick and springy underfoot and the air full of salt that tasted faintly metallic.

The sky crouched low, gray-green as a seal’s back, but the light was clean, the kind that made edges sharp without being cruel. She climbed past black sheep that watched her with yellow irises, then along a ledge where surf shouldered rock and burst into lace down below. Walking was the one rhythm she trusted—step, breath, step, breath—the same rhythm that had carried her since her grandparents raised her to keep moving when grief made time feel like solid mud. She touched the zipper of her jacket at her throat and thought, not for the first time, how long-ago sirens and shipwreck songs had probably sounded a lot like this wind.

It was at low tide that she heard the singing, a sound too round to be mere wind and too patient to be something mechanical. The basalt cliffs along the lagoon’s mouth had caves like organ pipes, and as water drained and air moved through them, they spoke a resonant chord that felt like it had been built out of the island’s bones. The hair along her arms stood as if recognizing an old language, though she had never heard anything like it before. At the edge of the lagoon, small cairns of rounded stones stood in irregular rows, not quite paths and not quite fences, their placements too deliberate to be accidents.

She crouched to trace a lichen stain and found, beneath it, a tiny groove carved in a spiral, a choice by a human hand lost to time. She learned quick where the locals would talk and where they wouldn’t, so that afternoon she ducked into the village’s only café, which served coffee that tasted of smoke and ocean. The woman behind the counter was gray-haired, her braid coiled like rope, and her name—Rúna—was written on a slate shaped like a fish. Rúna watched Barbra as if measuring not only what she wanted but what she was, then slid her a cup and a scone with a flick that said, Maybe you’ll behave yourself.

When Barbra asked about the caves, the woman’s eyes pinched, and her glance moved to the window, where the tide was turning. “We call them gates,” she said finally, a phrase ironed flat, “and gates keep what’s behind them where it belongs.” She wiped her hands. “Some families know them. Some keep them, so the wrong feet don’t go stumbling in.”

Barbra didn’t push; patience had earned her more truth than force ever had.

She told Rúna she wasn’t here to pry anything that didn’t want prying and meant it, and something in the other woman’s shoulders loosened a shade. They talked instead of sheep and weather and the way fog swallowed sound, and Barbra listened as if these were clues too. Back at the cottage she built a small fire that breathed smoke into her hair and made her freckles suffuse a glow she resented, and she washed her face in cold water, unflinching and bare. Her mind sparred with the ordinary until the extraordinary returned to tap the window of her attention.

Night dropped like a scarf, and the tide drew away until the lagoon’s floor lay slick and shining. The cave-mouths breathed music again, softer now and threaded with a whistling note that seemed to trace the edge of the sand. Phosphorescence stirred where the water had been, a faint green map drawn by invisible hands, and Barbra followed its filigree with the careful greed of a cartographer. Near one cairn, something hard caught under her sneaker and clicked like a tooth.

She knelt and freed a small, cloudy piece of mineral from the black grit, its facets dull but not dead, like a milky eye that refused to close. She rotated the stone and felt it tug at the light, a strange, clean tension that pulled a band of pale from the misted sky even though no stars showed. A memory flickered—an article she’d read about calcite “sunstones” and Vikings who used them to find the hidden sun—and she smiled, the kind of grin she never gifted to mirrors. She held the piece to her eye and turned slowly until a slender glow sharpened into a narrow line, pointing not to sea but along the curve of the lagoon toward a shadowed ravine.

Her heart stepped faster to match it, quick, decisive, practiced. She pocketed the stone and whispered to the dark, “You’re coming home with me,” already picturing it glowing on a shelf between a Nepalese prayer wheel and a jar of Sahara sand. In the morning the sky had heaved itself into blue, a surprise that made the grass look too green, like a storybook. Barbra went back to the café and ordered more smoke-coffee, letting the steam fog her freckles as if blurring them might make them disappear for ten minutes.

Rúna slid into the chair opposite her without invitation and set down something wrapped in netting that smelled faintly of salt and rye. “For your walk,” she said, eyes on the window, though her voice had softened around the edges. Barbra opened it and found bread, a sliver of brown cheese, and—nested between them—a torn corner of greasy paper inked with a diagram of the lagoon and a line of Faroese script: telja sjey frá fimtu. Barbra had her phone translate, but she already knew what it meant: count seven from the fifth.

Fifth what? Cairn, she thought immediately, because of the rows she had seen, and she felt the pleasant shiver of being invited deeper by someone who still pretended not to be inviting her at all. She thanked Rúna without making a show of it, tucked the paper safely into her jacket, and finished her coffee in silence. The room hummed with the undertone of a place accustomed to holding its breath.

When Barbra looked up to return the cup, Rúna was already gone, the bell above the door barely stirring. The tide was ebbing again when Barbra returned to the lagoon, the basalt organs tuning themselves to a deeper key as water left their throats. She stood before the lines of cairns and tried to see them not as stones but as an arrangement, like notes in a measure. The fifth cairn in the nearest row was slightly taller than its neighbors, with a flat capstone washed smooth as skin.

She set her heel against it and counted seven strides along a vector only she could feel, tuned by the low note and the sunstone’s private law. At the seventh, her toe struck a seam in rock where none should have been, and a draft of warm air slid over her ankles as if a sleeping thing had turned in its bed. There was a narrow cleft hidden behind a curtain of coarse grass, the kind of feature you would miss unless the air moved just right. She eased the grass aside and found the crack wide enough to slip through sideways, the basalt polished inside by passage too frequent to be made solely by wind.

From beyond came a sound like distant water and a pulse that felt less like noise than like someone putting a finger to her wrist. For a second she saw her grandparents’ faces—stern, tender, always steady—and knew they would tell her to measure twice, cut once, and bring herself back whole. She laid her palm to the stone, felt it hum under her skin, and wondered who had counted to seven before her and what they had found waiting in the dark.