CHAPTER 7 - The Stair of Shadows and the True Blue Sun

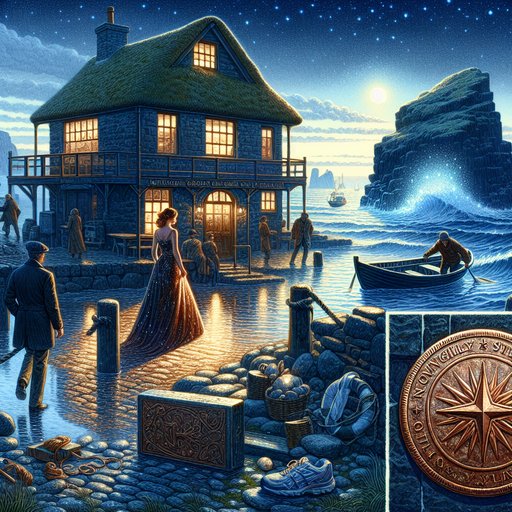

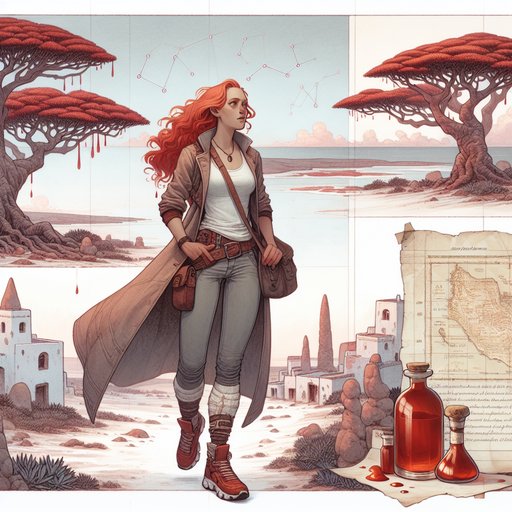

Barbra Dender, a 31-year-old redhead raised by her grandparents, arrives on Suðuroy in the Faroe Islands to chase an unusual local phenomenon called the Blue Sun. In Chapter 1, her stay in a turf-roof guesthouse above Tvøroyri puts her near fishermen who speak in guarded tones, and she finds a copper disk etched with a starburst and the word BLÁSÓL beneath a loose floorboard. A note warns her to seek a singing cave at slack tide without light. In Chapter 2, she probes the town but meets only suspicion, then enters the cave and discovers starbursts and cryptic marks as waves and a dim blue glow deepen the mystery. In Chapter 3, she temporarily retreats, dresses up for the harbor bar in glitter and Louboutins to clear her head, and later discovers an anchor plaque echoing her disk; she deduces the numbers mark tides. At dawn, a blue halo blooms around a sea stack when the tide slackens, and an arrow stone points to a kelp-choked cleft where figures block her path. In Chapter 4, two locals test her; she finds a niche with a copper lens, a bone flute, and a map fragment, then realizes it’s a decoy and reframes the puzzle around sound, locating a truer fissure marked BLÁSÓL skuggi. Chapter 5 reveals the harbor caretaker Suni as the sender of the note; Einar, the fisherman she met, joins her. Using the flute’s rhythm and the copper disk as measure, she opens a resonant chamber where the Blue Sun’s smuggler legend cloaks an acoustic lighthouse and sanctuary guarded by families. In Chapter 6, new silhouettes demand the disk; they are guardians—led by Ragna—staging a ruse to misdirect real pursuers. The chamber’s lens projects a map of blue veins and starburst nodes; Barbra’s starburst pin hides the true key in microgrooves, and Ragna entrusts her with a bead to place at a cairn at Hov and a cod-skin scroll. Helicopter lights sweep the cliffs as a new passage opens, forcing Barbra to choose. In Chapter 7, she trusts the sound and ascends a secret stair, places the bead at Hov to complete the pattern, and helps the guardians misdirect and flood a decoy tunnel, preserving the sanctuary. Her integrity is rewarded with the replica BLÁSÓL disk as a relic for her cabinet. The Blue Sun remains hidden, its secret intact, as Barbra leaves Suðuroy with earned trust and a new story to tell.

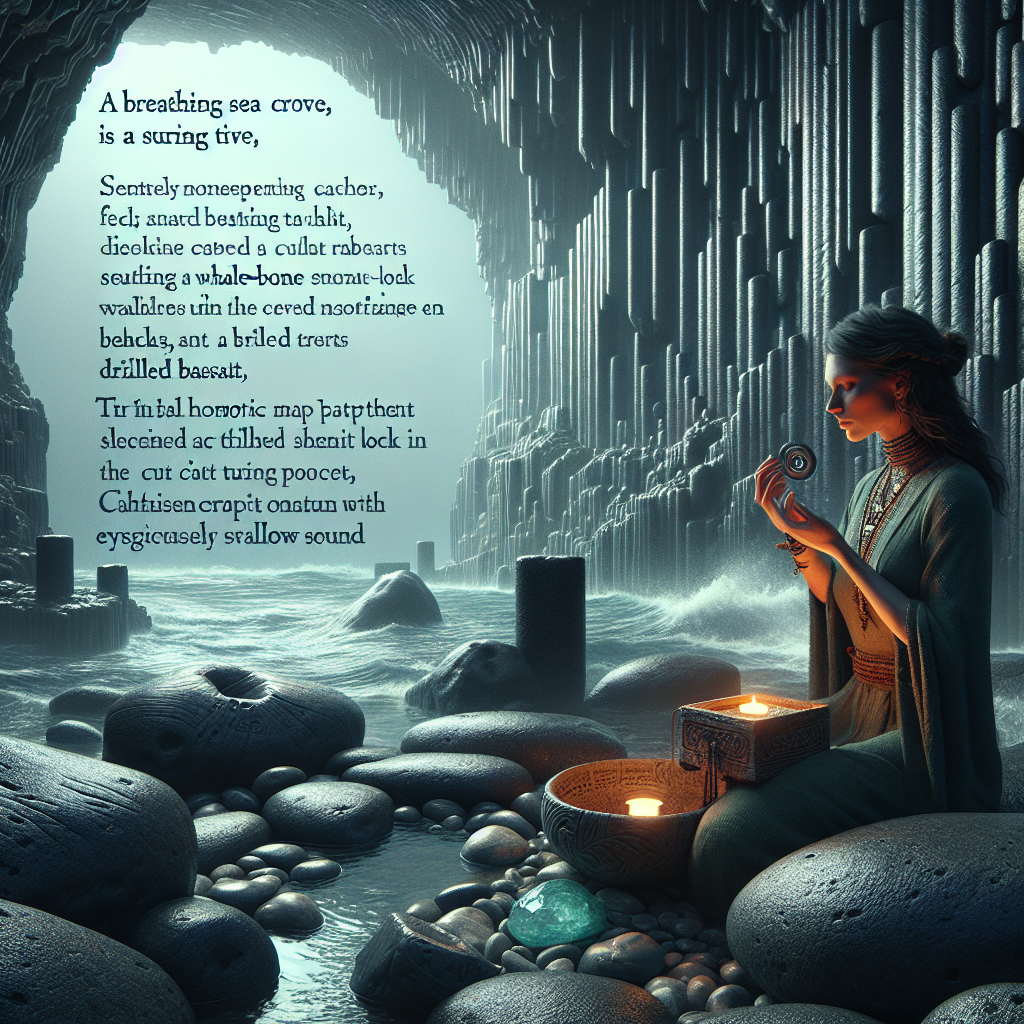

The threshold pulsed, a blue seam in basalt breathing like a tidepool, and a helicopter’s beam sliced the mist in a white arc that briefly turned my hair into a copper spark. Einar’s breath warmed my shoulder in the cold seam, and Suni’s hand hovered near the bone flute, ready if I faltered. The copper disk in my pocket felt heavier than it ever had, as if the etched BLÁSÓL could drag me into a choice I wouldn’t be able to undo. I was in tight jeans and my blue-and-white Asics soaked by spray, leather jacket dark with brine, freckles prickling under the chill—familiar armor for a woman who learned to move alone.

I looked at the starburst pin on my lapel and heard, faintly, the rhythm buried in its microgrooves answer the chamber like a heartbeat I could follow. I tapped the BLÁSÓL rhythm against the stone—short, long, short-short, a pause, then the steady thrum Suni had taught me to feel more than hear. The blue seam expanded; steps tilted out from shadow one by one, slick as seal skin, a stair that existed only because sound told the rock to remember its shape. “Go,” Einar whispered, rope looped over his shoulder, eyes reflecting a pocket of blue; his voice made something in me want to anchor, which was exactly why I couldn’t.

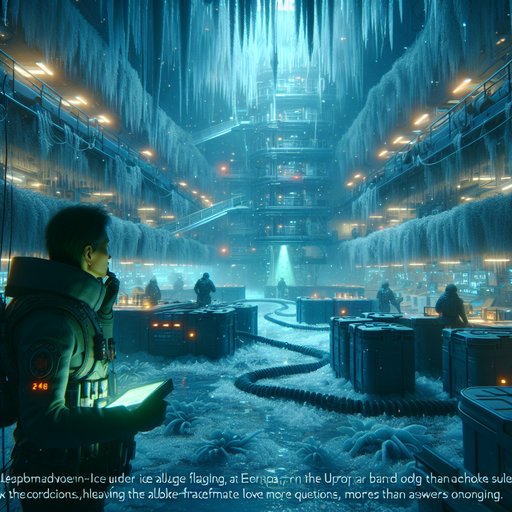

I went first. The stair swallowed our footsteps, and the seam folded behind us like a closing eyelid, muting the rotor’s chop to a distant mosquito. We climbed between ribs of basalt that drank light, each landing set with a shallow cup that caught seepage and chimed when drops fell at just the right interval. The stair spiraled into a chamber no larger than my guesthouse’s kitchen, where a slit in the ceiling split the sky into a thin gray river.

The sea sighed below like a sleeping animal, and Ragna’s face, pale and firm, appeared in another slit above as if pulled from the rock by the same sound. “They’ve taken the decoy,” she called down, not triumphantly but with relief, her voice softened by the stone. “The lower tunnel’s flood will send them to the outer pool; no one gets hurt if they follow the lit path.”

I had almost forgotten the bead in my pocket until the scroll shifted with it, cod-skin rasping my fingers with a dry, old whisper. Ragna nodded toward the landward side, where an opening was no more than a cat’s width at first glance.

“Hov’s cairn listens, not looks,” Suni said, coming to my side with care, like a grandfather steadying a child on wet stairs. “Place the bead where the wind and the sea can speak to it together, and the lighthouse will remember its duty.” Einar met my eye with a question that wasn’t about maps, then stepped back to give me room to choose. Outside, dawn had only insinuated itself into the fog, a gray that invited other colors to be imagined rather than shown. I climbed the moor path in the hush between wind shifts, the ground springy under my Asics, wet heather smearing my jeans where it leaned in.

Hov’s cairn was a shoulder of stones, friendly in its permanence, with a hollow like a palm in its side if you knelt and pressed your ear to it. The cod-skin scroll crackled as I unrolled it, the script inked in a hand that had known more storms than letters, telling of whales threading dark water by song and people who learned to mirror that song with stone. Place the bead at the notch, it said, and the Blue Sun would cast its halo where it should—and nowhere else. The notch was colder than the air, as if the cairn had been holding its breath, waiting.

I slid the bead into the socket and felt it seat with a soft, satisfying click that traveled into my fingers and up my arm. Around me, the wind shifted to the northwest, and a gull’s cry curved inward as if drawn by a bowl. The sea’s voice in the cave below became a single note, then a chord, the rhythm the same as the pin’s microgrooves but larger, more forgiving—less a code than a memory. A seam of sky to the west lifted its lid and for a moment I saw, even in daylight, the faintest suggestion of blue at the sea stack’s base, as if the Blue Sun blinked once to say yes.

By the time I slipped back through the cat’s-width, Einar had unspooled his rope and tied off a belay in case I had to descend fast. Ragna had descended a level with another guardian I recognized only by her salt-stiff braids, her eyes briefly settling on the pin at my collar. “Your bead woke the north wind,” she said, half-amused, half-astonished, as if something old had shaken off sleep. “And your stair sealed the seam behind you,” Suni added, in the same breath reminding me that secrecy wasn’t a wall but a rhythm you chose to keep.

The helicopter’s sound fell away to the south as if the pilot, bored of fog and empty stone, had turned back to fuel. We found the lower chamber calmer now, its pool glassy and the blue veins along the wall muted like veins under skin. The copper lens waited on its cradle where I had left it, gleaming like an eye, and the projector’s arm was still lined to the sea stack node. “They saw what we wanted them to,” Ragna said, and a pulse of guilt tapped the back of my throat—this was a lie told for a truth to live.

Einar stood near me, close enough for his scent of salt and diesel to fold into the chamber’s mineral breath, and said softly, “My network will report only the weather and an unremarkable tide.” His kindness had no romance in it now, only respect; it steadied me more than I liked to admit, which, given my history, said enough. I passed him the cod-skin scroll, and he smiled without taking it. “No,” he said. “That belongs with the cairn and the wind.” Suni took it instead, tucking it into a waterproof pouch at his chest.

“The families will keep melody with the bead,” he said, as if speaking to my grandparents rather than to me. “If you hadn’t listened, we’d have had to close the chamber for a season.” My freckles prickled in the glow—ridiculous, to be self-conscious when the walls themselves were listening—but the honesty of being seen and still trusted smoothed their itch. We unwound the ruse with care. Ragna led a return of water into the decoy tunnel, a proper flood this time, one that pushed the last of the pursuers to the outer pool where a current tugged them harmlessly against a ladder bolted to rock.

Far above, a pair of trucks rumbled away on the road back to Tvøroyri, their sound diminished by the cave’s selective ear. It was a relief so physical I felt my shoulders drop, the way they used to after my grandmother wrapped me in a towel on rain-heavy afternoons. I turned the copper disk over in my palm; its starburst caught the blue and answered it with a warmer flash, like embers under driftwood. Ragna came to me with something wrapped in sailcloth, the corners dark with salt that had crusted and softened over decades.

“You do not keep our keys,” she said, and a smile ghosted the corners of her mouth. “But you keep stories. This one is safe to keep.” She unwrapped the replica disk from the staged handover—the BLÁSÓL starburst crisp, the copper younger than the one hidden under my guesthouse floor, its back scratched with a single curve like a wave. “Let it sit in your glass cabinet and remind you that there are secrets that breathe only because strangers sometimes choose not to pry.”

I nodded and tried not to look as if I was holding my breath until the sailcloth lay in my hands.

It was an ordinary weight to be so full of time. The starburst pin stayed at my collar; Suni had shown me, quietly, how to tilt it to lock the stair and how to keep it inert anywhere lit by electricity. “It prefers fog,” he’d said with a shrug that was more knowledge than humor. Einar squeezed my wrist, brief and warm, then let go because we both knew I didn’t belong here, and belonging was not the same as being trusted.

We left as the tide inhaled, through a seam I would not have seen alone, and came up among grasses glazed with dew. The harbor lay to our left like a thought half-formed, and the sea stack wore a filigree of spray that caught a slit of sun, barely there, enough to gather a ghost of blue at its rim. I watched its halo for a long minute, until my eyes watered and the color dissolved in daylight. It was not a spectacle for tourists; it would never be.

That was the point, and I felt the relief of knowing I didn’t have to insist otherwise. At the turf-roof guesthouse, I packed with my usual economy: jeans rolled, tank tops folded to thin rectangles, leather jacket slung across the case. I slid the sailcloth-wrapped replica disk between shirts, careful as if it were made of spun sugar, and tucked the starburst pin’s point into the fabric so it wouldn’t catch on anything. My face in the small mirror was wind-burned, hair wild, freckles loud as constellations I hadn’t asked for; I smiled anyway, a rare indulgence, because there’s a kind of beauty in being exactly the woman a place needs you to be for a while.

The shelf by the window where I had found the first disk looked plain again, a floorboard that would squeak for no one but me. I left the key with a note that said nothing at all about caves. On the quay, Einar kept a careful distance that made our goodbye easier. “The weather’s turning,” he said, as if we hadn’t both watched it turn and ridden it.

Suni’s handshake was a dry scrape, his eyes warm with the humor of a man who has outlived too many sharp seasons to doubt kindness. Ragna did not come down; she lifted a hand from where the cliff met the fog, and that was somehow enough. The ferry’s horn rolled along the water like a deep laugh, and I felt something loosen beneath my breastbone. As the ferry pulled away, Suðuroy receded into its own weather, taking the Blue Sun with it, the halo tucked back under slate.

I thought of my glass wall cabinet at home, of the copper disk that would slip into the field of other stories—clay, wood, glass, bone—each a testament to seeing something old and leaving it as you found it. I would tell the ones who wanted to listen about sea stacks and singing stones and a light you could misread as magic if you weren’t listening, and I would omit the parts that did not belong to me. The wind flattened my hair and made my eyes water, which was fine; it could be the salt. Relief, at last, felt like open water, and I let it carry me forward.