CHAPTER 3 - Night on the Quay and the Anchor Named Blásól

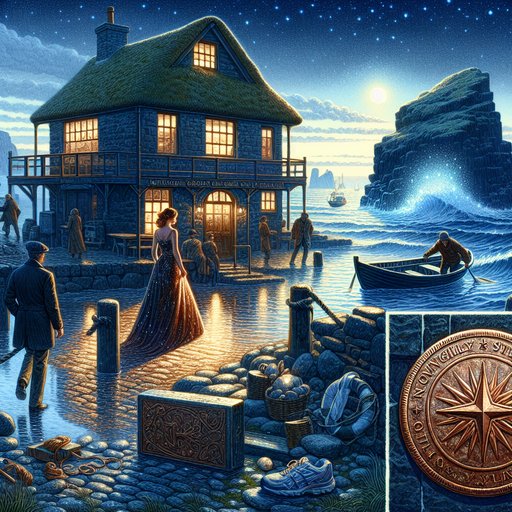

Barbra retreats from the singing cave as the tide turns and the blue glow fades, leaving her investigation at a frustrating dead end. Back at her turf-roof guesthouse she studies the salt-crusted copper disk etched BLÁSÓL and its faint coordinate-like marks, but nothing resolves, so she dresses up in glitter and Louboutins to unwind at a harbor bar. A flicker of chemistry with a local fisherman yields no answers, yet a late-night stroll along the quay brings an unexpected clue: a weathered anchor plaque engraved with a starburst, the word BLÁSÓL, and numbers echoing the disk. A cautious old caretaker hints that local families keep the Blue Sun secret and that the 'singing' is tied to shadow. Back at the guesthouse, Barbra realizes the numbers may be tide times rather than latitude and decides to test them at dawn. Alone on the headland in her Asics, she witnesses a blue halo bloom around a sea stack at slack tide and notices a half-buried stone with a carved starburst and an arrow that points toward a kelp-choked cleft. As she moves to follow it, a small boat cuts its engine and figures step into her path, the cave’s song rising again—do they want the disk or to stop her?

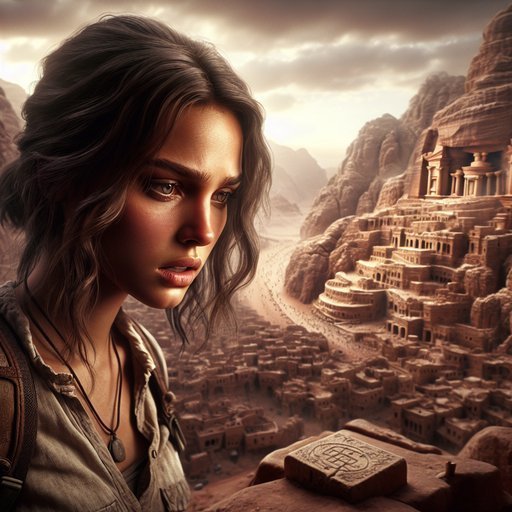

The cave breathed in the dim like a sleeping animal, the blue pulse ebbing as if holding its breath with the sea. Barbra pressed her palm to the cold wall until her fingertips numbed and tried to commit the carved starburst to memory, but the rhythm of water shifted, and the voices—real or imagined—seemed to recede into the stone. She had promised herself once to survive tides and men by knowing when to retreat, and she obeyed that old rule now, inching back toward the mouth with her shoulder against basalt. The exit was a bruise of lighter black, the floor slick beneath her Asics, spray needling her face as the cave exhaled.

When she finally spilled onto the shingle, her jeans damp at the knees and breath punching clouds into the grey air, the only thing chasing her was the long hush of the slack tide ending. Back in the turf-roof guesthouse above the harbor, she let the shower knock warmth back into her muscles, the steam fogging the small mirror until her freckles were just a constellation. She hated how they showed when the chill brought her color up, but she smiled anyway at the absurdity of minding freckles when she had just crawled out of a singing cave. On the tiny table by the window she spread the copper disk, the salt crust flaking beneath her careful fingernails, and compared the faint numbers around the rim to the penciled rubbings from the cave.

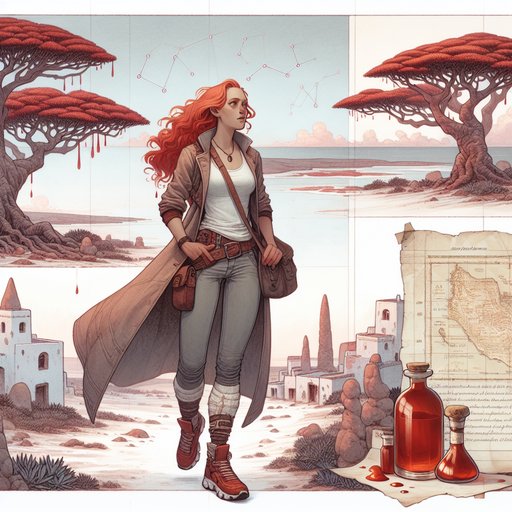

They refused to join, as stubborn as the silence she met on the quays in daylight. When the wind rattled the pane and the sense of going in circles threatened to sink her, she decided she needed to slip that circle entirely. She chose armor of a different kind: black skinny jeans and a shimmering silver jacket from the glitter end of her collection, a white tank that felt like a clean page, and a pair of Louboutins she kept in their box like treasure. She laid the red-soled pumps on the bed and ran a finger along one heel, their fine leather a ritual that steadied her more than makeup ever could; she rarely bothered with more than a swipe of balm.

Her hair she left as it was, red waves tamed only by the salt air’s insistence, and she shrugged into the jacket, its sequins catching the low light. The copper disk slipped into the inner pocket—she felt wrong without it now. On the cobbles down to the harbor she stepped carefully, proud and protective, placing each heel like a promise. The harbor bar gleamed with bottles and the sheen of wet coats, some Faroese folk tune lifting over the clink of glasses and the soft rumble of a language she didn’t speak but loved to hear.

A band with a tin whistle, a fiddle, and a drum sat by the window, heads bent together as if over a secret, and she let the rhythm loosen a muscle she hadn’t realized she’d clenched. A fisherman with sea-grey eyes introduced himself as Eirikur and asked if she’d like to dance, and for a song or two she let herself be led, laughing when her heel snagged a floorboard and he steadied her with both hands. He smelled of wool and smoke, kind hands on a frame honed by weather, the sort of person she could fall for for a week and then leave on good terms. When she asked, eventually, about the Blue Sun, he looked away, as if watching tides that weren’t in the room, and the wall of silence slid gently back between them.

They took their drinks outside anyway, because the air had ironed itself smooth and the drizzle had abated into a salt damp that made everything taste more itself. The quay lay like a spine, ropes swollen dark and cleats shining, gulls knifing the sky above moored boats that creaked in their sleep. Eirikur talked of storms and nets and the way the sea remembers you if you respect it, and Barbra listened, wanting to ask more and knowing he wouldn’t say it. She trailed her fingers along a weathered capstan, every groove a story she could feel without being told.

Then, under the dull glow of a sodium lamp, she saw it: a rust-dark anchor mounted on stone, a small brass plaque green with age, its face scratched by time but still legible—BLÁSÓL—above a tiny starburst and a neat line of numbers. The name struck her like cold, her skin prickling under the jacket, and she forgot the pumps as she crouched, balancing on the balls of her feet so the heels wouldn’t scrape. She wiped at the plaque with her sleeve, the sequins rasping metal, revealing the starburst’s lines and the numbers beneath—too orderly to be dates, familiar in the way the disk’s faint marks were familiar. “What’s this anchor from?” she asked, looking up, but Eirikur had turned toward the harbor’s black mouth, his jaw working as if on a word he couldn’t say.

“Old things,” he said finally, the two words small and heavy. He touched her elbow, not quite a goodbye, not quite a promise, eyes apologetic, and then he was already walking away, boots sure on the wet stone, leaving her with the plaque and the echo of a dance. Alone, she took a photo with her phone, then a second with the flash off, then held the copper disk beside the plaque. The starbursts were not identical—one more geometric, one hand-carved—but they shared a central ratio that pleased her pattern-loving eye, as if both were versions of the same sun.

The numbers on the plaque, when she mouthed them, caught on her tongue like a familiar tune whose words she’d misplaced. Across from the anchor a boathouse door stood ajar; inside, the smell of old rope and diesel and dried salt was the smell of every harbor she had ever loved. On a battered table lay a chart of the local waters, pencil lines noting hazards, and she set the disk on it, nudging until the etched points seemed to align with headlands she’d walked that afternoon, but the result was only a feeling, not a map. She realized she wasn’t alone only when the door lifted and an old woman stepped into the doorway, the wind making a frame of her grey hair.

The woman’s eyes took in the glitter jacket, the red-soled shoes just visible under the table edge, the copper disk catching the meager light, and then came back to Barbra’s face, unruffled. “You found our anchor,” the woman said in careful English, her mouth shaped by Faroese vowels. “Blásól was a boat once, and before that a word we don’t say at sea.” Barbra spoke softly, because the room asked for it, and she spoke with the honesty that had opened more doors than any trick. “I won’t harm your secret.

I just want to understand it.” The woman nodded as if this matched her reading of Barbra, then tapped the chart near a narrow shaded cleft. “Shadow,” she said. “The singing is clearer behind it.” And then she closed the boathouse door with the gentle certainty of someone who had already said as much as she would. In the guesthouse, under the slanted roof and its wind-rattle lullaby, Barbra slipped off the Louboutins and set them in their box, smoothing tissue paper around them with the same care she gave to her artifacts at home.

Her feet missed the give of her Asics like a body misses a morning ritual, and when she sat cross-legged on the bed in her tank top, the glitter jacket draped over a chair, she opened her photos. The numbers on the plaque were not spaced like latitude and longitude; the separators were wrong, the second unit too high. They looked, she realized with a sudden brightening, like a sequence a sailor might consult in a tide book. She pulled up the tide tables she’d noted that morning and, heart lifting, saw those numbers match the slack tide at new moon for this very cove.

She was awake before her alarm, an excitement gentler than caffeine and more reliable, and she dressed back into herself: tight jeans, blue and white Asics, and her floral denim jacket, fewer sequins and more sky. The horizon was lifting from black to iron blue when she took the cliff path, the sea muttering and the wind colder with promise than with spite. The coordinates-as-times began to tick in her head like a metronome, and by the time she reached the headland above the sea stack, the tide was reaching that held-breath moment. She pressed the copper disk to the stone fence and watched as the first hint of a halo, thin as a thread and blue as glacial ice, stitched itself around the stack.

As the tone built—wind through a blowhole? water in a hidden pipe?—she noticed a low stone half-buried in turf at her feet, its top carved with a weather-softened starburst and, to one side, an arrow pointing away from the sea. She brushed the turf aside, revealing the arrow’s direction more cleanly, and felt that reliable happiness she always felt when something in the world admitted her hint by hint. It pointed toward a notch where the cliffside dropped into a kelp-choked cleft, a shadow darker than the rest, the sound there deepening as if tuned.

The blue halo thickened for a heartbeat, then thinned, and the singing settled into a pitch that curled into her ribs like a question. She started along the narrow sheep path, testing each step, breath steady, the disk warm under her palm. Somewhere below, a small engine coughed and died to silence, and when she rounded the last gorse she saw them—two figures, backs to the water, faces turned toward her, one of them lifting a hand not in welcome but in warning—and a voice, closer than she expected, asked almost kindly, “Do you have the disk?”