CHAPTER 2 - Slack Tide and Sealed Mouths

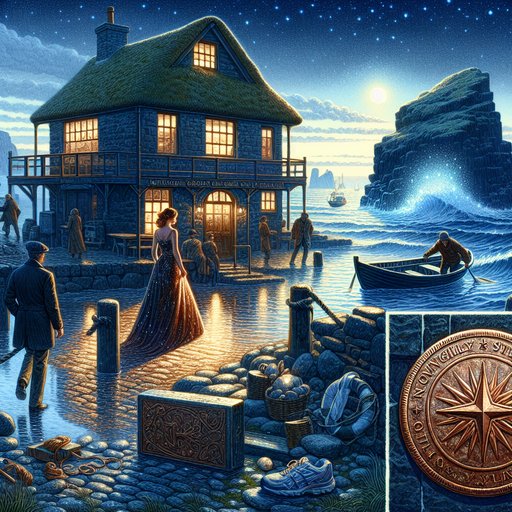

At dawn in Tvøroyri, Barbra Dender wakes in her turf-roof guesthouse, pockets the copper disk etched with BLÁSÓL and a warning note about a singing cave, and sets out in her jeans, tank top, Asics, and leather jacket. She probes the harbor for information, but fishermen and townsfolk close ranks, offering only terse cautions. At the small museum and library, she confirms the time of slack tide but finds no guidance that advances her search. Hiking the cliffs, she is warned off by two locals who clearly know more. Determined, she returns at slack tide and enters the cave without a light, where she discovers a carved starburst and cryptic marks that seem like a riddle but give her no clear path forward. The sea begins to stir, voices and footsteps hint someone else is near, and a dim blue glow pulses deeper inside as the exit darkens, leaving Barbra facing a perilous choice and an unseen presence.

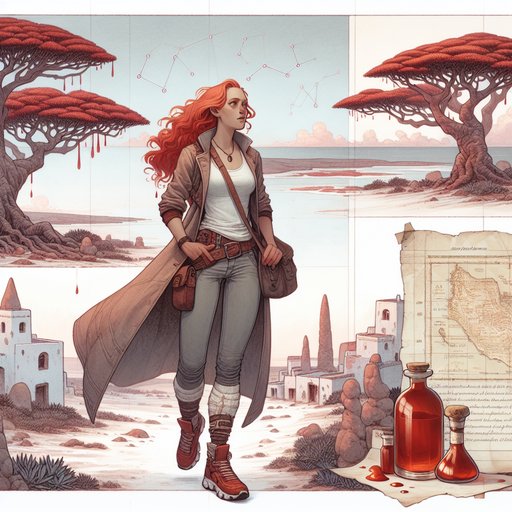

Wind rattled the turf along the guesthouse eaves as gray light spread over Tvøroyri, and Barbra stared at the mirror, tilting her face as if she might catch it unguarded. The freckles she’d carried since childhood stood out sharp against the pallor of morning, an unwanted map across the bridge of her nose; she swiped a knuckle over them anyway, knowing she wouldn’t bother with makeup. She pulled on tight jeans and a white tank top, laced her blue and white Asics, then shrugged into her black leather motorcycle jacket, its shoulders creaking like a well-broken in saddle. The copper disk and the folded note went into her pocket, cool and secret against her hip as she headed for the harbor.

She thought of her grandparents’ kitchen in summer, how they had taught her to trust her feet and her curiosity when no one else would help. The harbor was a bustle of boots and gulls, diesel and iodine, a choreography of ropes and hands as boats nudged hulls like restless seals. Barbra walked the wet planks, feeling the slick grain under her sneakers, and picked a fisherman with storm-blue eyes and a beard braided into two neat ropes. “Singing cave?” she asked, careful not to sound breathless with it, and he looked at her freckles before he looked at her eyes.

“You want a song, go church,” he said, turning away to coil a line with exaggerated patience, the polite wall going up brick by brick. A younger deckhand glanced at her jacket, then at her pocket as if he could see through leather to copper, and shook his head without a word. She bought a coffee from a kiosk that smelled like cardamom and old woodstove, warming her hands around the paper cup while she watched the harbor take stock of her and turn inward. The woman behind the counter, hair tucked under a knitted cap, smiled with half her mouth and slid over a biscuit as if to soften a rebuff.

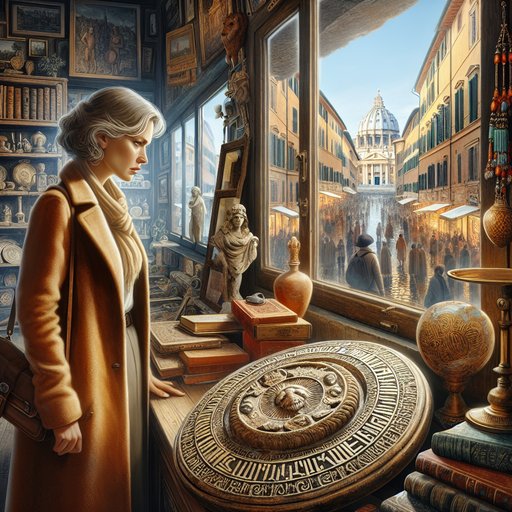

“Weather will turn by afternoon,” she said, voice mild and neutral. “Some places seem closer then than they should.” Barbra tucked the biscuit into her jacket pocket with the note, another small weight, and kept moving. The town’s little museum and library shared a low basalt building hung with photographs of men in oilskins and women in shawls who looked as if they had never had time for nonsense. Inside, books smelled of lanolin and salt, and a glass case displayed whale-bone tools alongside a faded tide table printed in lilac ink.

Barbra traced the columns, reading the tides like an appointment book until she found what she needed: slack would come just after two in the afternoon. She copied it into her notebook, a ritual as steady as breathing, and turned to the shelves for anything on coastal acoustics or local legends. A librarian with silver hair and a sweater the color of stormwater hovered nearby, arranging cards in a drawer without looking at Barbra directly. “BLÁSÓL?” Barbra asked, tucking a strand of red hair behind her ear, trying to keep impatience from fraying her voice.

The librarian’s hands faltered for a heartbeat, then kept moving. “Blue sun? Pretty words,” she said, and closed the drawer with a soft click, the sound of a door closing without a slam. “If you like photographs, the cliffs have them, always different,” she added, as if switching the subject would make the word evaporate in the air between them.

Barbra stood there a moment, remembering how, at four years old, she had learned that even good people sometimes couldn’t help you carry the heaviest things. By noon the wind had freshened, driving a corrugation across the water, and Barbra followed a sheep path out of town, her steps sure and even. Suðuroy unfurled in green flanks and black teeth, cliffs biting at the sky, the world reduced to stone, grass, and the breath of the sea. She paused at a cairn stacked with old hands’ care, feeling the subtle thread of sound in the air, a low harmonic that lived in rock more than wind.

Below, a cleft opened toward a pebbled cove where surf combed in long, glassy tongues and slid out again, gathering itself. The hum was there—the cave was singing already, as if warming up. She wasn’t alone on the path. A man with a wind-peeled face and shoulders like a pier post stood beside a woman whose hair whipped in black banners, both of them wearing the look of people who knew exactly where stones were buried.

“Turn back,” the man said, not unkind, but as if the words were a harbor regulation. Barbra smiled with the politeness her grandparents had stamped into her and said she only wanted to listen to the sea. “It will talk to you,” the woman said, eyes sliding to the jacket pocket that held the disk. “It doesn’t always say what you think.”

They waited until she took two steps back up the path, their bodies making an answer as firm as a locked door, and then, satisfied, they cut across the slope and were gone.

Barbra waited ten minutes, counting breaths and sheep, then took the long way down over wet basalt stairs carved by feet older than maps. At the cove, she checked her watch: five minutes to slack. She took her headlamp out of her pack and then, remembering the note’s warning, put it right back. The absence of light felt like a promise she had agreed to keep.

The cave mouth was a low O of shadow strung with weed like old lace, breathing as the tide exhaled and inhaled. Barbra stepped when the sea retreated, timing her own breath to it, and slipped inside as if crossing a threshold into a stranger’s kitchen. Darkness pressed against her, a velvet and salt presence, the world reduced to touch and sound; she put one hand to the wall, feeling the basalt cooled by centuries of wind and weather. Somewhere ahead, the cave droned a note that warped and rose, the voice of a bottle if the ocean were a giant mouth.

When she hummed under her breath, the tone changed, catching and answering like a tuning fork. Her fingers found a change in the wall, a shallow recess, and she explored the edges with careful, blind patience until her fingertips read the shape: a starburst, not decorative but purposeful, each ray a tidy incision. She pressed her palm flat and felt faint peck-marks above it—five, then three, then five again—nothing that translated into sense, just the muscular memory of a pattern. Above the starburst, someone had carved three words in a hand as steady as a surveyor’s: Syng án ljóss.

Sing without light. It was a clue by shape and intention, and it told her nothing she didn’t already know. She drew the copper disk from her pocket, slid its cold face against the recess, and the fit was almost but not quite right, as if the disk had been made by someone who had only ever seen the carving in dreams. She rotated it, listening to small, meaningful scrapes that promised secrets they never delivered.

Water lapped at her ankles, retreating and returning like an animal testing its courage, and she frowned into the dark. The disk wasn’t a key, or if it was, she did not yet have the door. She slid it away, relief and disappointment in equal measure. Someone moved behind her—no scrape of shoe or rustle of fabric, only the tiny shift of air that a person makes when shifting weight.

Barbra froze and turned her head, uselessly, toward the mouth of the cave that now seemed smaller than it had minutes before. “Hello?” she called softly, careful to let the word fall more than fly, so the sound wouldn’t wake whatever slept here. A pebble clicked against another pebble. She could hear her own heartbeat, counting how long she’d been in the cave, how long the sea would be patient.

When she reached the entrance, the light outside had flattened into a pewter sheen, and the low tide, faithful as a clock, had already begun to change its mind. On the slope above the cove, two figures stood like cairns, profiles cut to stone—perhaps the man and woman from the path, or two different guardians wearing the same silence. “Don’t follow the song,” one called, voice carried in careful pieces by the wind, the words landing at her feet like shells. “It belongs to the dead.” Then they turned and vanished behind a knuckle of land, as if they had only ever been thought rather than flesh.

Deeper in, the hum gathered itself and shifted, a second voice layering under the first until the cave breathed intervals like a sleeping beast. Barbra’s skin tightened with it, the sound reaching for something in her sternum like hands. A faint light bled and receded, then bled again, not white but a bruised, translucent blue, as if the water itself were exhaling with a glow. A rope slid toward her ankles, coiling as if it had made the decision on its own, and she caught it reflexively, feeling salt-wet fibers and a knot she didn’t recognize.

Who had offered her the line—friend, warning, or bait—and how much time did she have before the sea closed its mouth for the day?