CHAPTER 7 - The Note Beneath the Silence

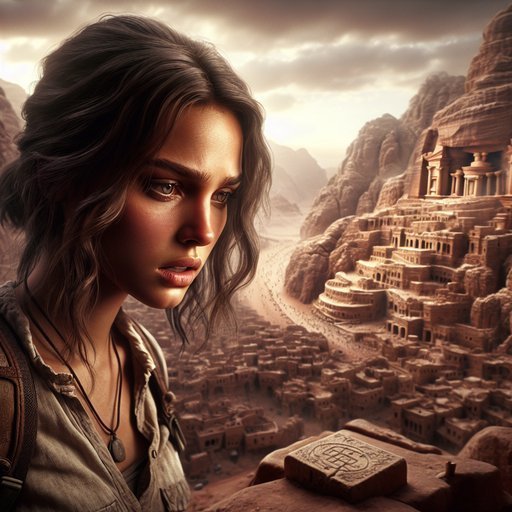

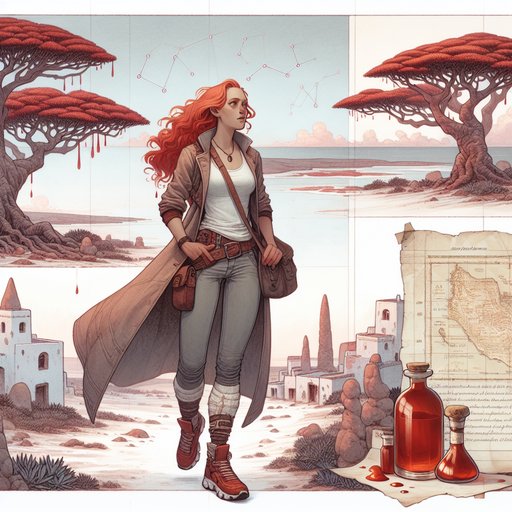

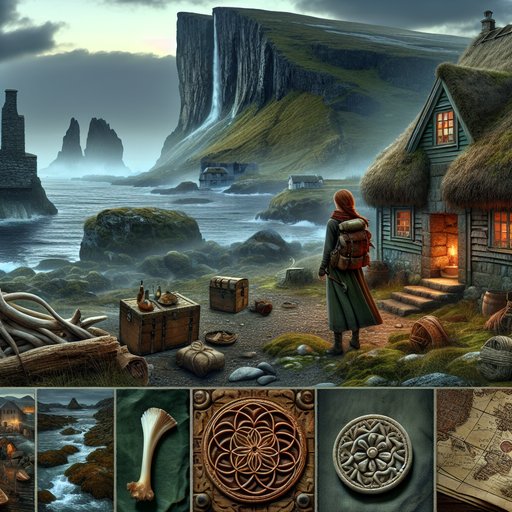

Barbra Dender, a 31-year-old red-haired traveler raised by her grandparents after losing her parents in a car accident at age four, arrives in the Faroe Islands seeking the unusual solace of remote places. From a turf-roof cottage in Saksun, she hears a dusk hum tied to the fjord and uncovers cryptic hints: a shanty’s mention of the Song Gate, a vellum marked with a six-petaled rosette and tidal notations, and driftwood etched with lines. Locals are wary: a woman named Ragna and guarded villagers offer warnings, and a kelp-tied whalebone token with a rosette and the words “turn back” is left at her door. Undeterred, Barbra follows the clues to Tjørnuvík, where a barnacled rosette and a cave lead to an acoustic puzzle responding to resonance and the ebbing tide. Experimenting with song, she opens a small chamber and finds a resin-sealed box with a bead and a riddle: “When the sea walks backward, the valley sings twice. Bring the bone not from sea.” Misled by a decoy passage, she rethinks the problem and turns inland. In Saksun, an upside-down rosette on a church lintel yields a hidden stair when she sings against the valley’s double echo at dusk. There, an elderly woman with a rosette brooch, Sigrið, admits to leaving the warning token but recognizes Barbra’s integrity. With Sigrið’s land-bone flute, a basalt “knee” wedge, and Kári the fisherman’s reluctant help, Barbra confronts the Song Gate’s true secret: silence used to cancel tones. They navigate baleen baffles, shifting relief maps, and ring-locks requiring multiple harmonics. As the equinox tides approach, a hooded intruder slips inside, twisting the hum with a human whistle and scoring fresh cuts into a seal. The trio pursue him into the vault’s heart, where the families intend to relocate their archive before the sea “walks backward.” They discover the intruder is a young keeper testing Barbra’s intentions, and together they complete the triple-harmonic sequence that safely transfers the archive deeper underground. The families, now confident in Barbra, keep the mystery intact and present her with a retired basalt tuning disc incised with the six-petaled rosette, a fitting relic for her collection. Barbra leaves the Faroe Islands with the Song Gate’s secret preserved, the hum quieted beneath the silence, and her glass cabinet awaiting a new story she will tell to anyone willing to listen.

The iron-bound door sighed and the passage swallowed the last pale smear of dusk, sealing it behind us like a promise. Barbra, in her tight jeans and tank top beneath a black leather jacket, tested her footing as the floor pitched subtly toward the soundless heart below. Her blue and white Asics gripped the slick stone, and she felt the old self-sufficiency coil in her chest—the same grit her grandparents had coaxed into her after she lost her parents, the same discipline that kept her walking long distances until muscle turned into quiet armor. She brushed a red strand from her freckled cheek, grimacing at the constellation she still disliked, and glanced at Sigrið and Kári.

Ahead, the hooded silhouette flicked out of sight around a rib of rock, the last note of his human whistle bleeding back into the earth like a taunt. The corridor breathed. Baleen-like baffles along the walls bent the air into curving pockets, little coves of almost-sound that shifted as we moved. Kári’s lantern made warm stitches along the basalt, and Sigrið palmed her land-bone flute, the humble sheep’s bone polished by decades of care.

Barbra held the basalt knee wedge, felt its heft, and remembered the way sound could be canceled by measured silence, the countertone that had pried the earlier ring-lock apart. Fresh cuts scratched the rosette seal we’d passed—thin, impatient gouges that said the intruder had a key and a deadline, but not the patience for the old ways. We entered a chamber like a deep bell struck mute, its ceiling scalloped for echoes we were not meant to hear. At center stood a flat plinth that sloped toward a black slit, the stone barely damp with the memory of the tide.

When the sea walks backward, Sigrið had said in Chapter Four’s whisper, and the valley sings twice. Barbra breathed and let her ear find the double echo, one close and one far, like two heartbeats in a single chest. She raised her voice into the hush, a low vowel aligned with the faint undertone in the rock, then denied it with a held breath, the wedge pressed into a notch until the air itself seemed to tighten. The plinth shivered and a seam eased open, not down toward the sea but sideways, a hidden corridor revealed in a long sigh of cold air.

Beyond, we saw the relief map again, its ridges quivering, the fjords and valleys shifting with our breath the way they had before. Only now the heart-stone inset at the center pulsed with a deeper warmth, as if the island’s pulse had quickened with our arrival. Kári swore softly; Sigrið touched the stone with two fingers and closed her eyes. “He’s taken the softener pin,” she murmured.

“No vandal, then. A keeper’s hand—young, quick, and too sure.”

We tracked the intruder along a curve of wall that sang like a shell when you leaned your ear to it, the faintest thread of human whistle woven through the bedrock’s low hush. The corridor spilled us into a gallery of niches, each one a pocket for an object we were not allowed to take, shelves of bone flutes and rosette discs and vellum scrolls wrapped in waxed cloth. Barbra’s fingers twitched at the sight—collector’s reverence, not greed—and she felt the gravity of families who had protected this place through barrels of weather and centuries of forgetting.

At the far end, the silhouette threw back his hood and turned, a narrow face lit by the lantern’s tongue with the nervous light of youth. He was barely older than Barbra had been when she started traveling alone—mid-twenties, perhaps—his hair a dark blur, his eyes sharp as hooks. “Leivur,” Sigrið said, a sigh and a warning braided together. He raised his hands, palms open, fingers marked with fine scars from rope and blade.

“I made the cuts,” he admitted, and the honesty had the clipped rhythm of someone who has rehearsed it. “To draw you in and to see if she”—his glance flicked to Barbra—“would hear what we need her to hear.”

Kári grunted, half anger, half relief. “You could have told us.” Leivur’s mouth tilted. “You would have said no.

You would have moved the archive without the third ear and risked the shudder tearing the vault, like the year of the broken calves.” Barbra felt the air contract around old pain and did not ask. She looked at Sigrið, who weighed Leivur the way she weighed bone and tide. “We do it properly, then,” Sigrið said. “Three harmonics and the cancelling breath.

And then we are done.” Leivur nodded once and turned toward a low aperture breathing cool air into the gallery. Beyond, a narrow chamber waited, domed like the inside of a conch. Three rosette seals sat at shoulder height, equidistant, each a different texture: one smooth basalt, one ribbed like a whale’s tooth, one varnished wood the color of a storm. Leivur handed Barbra a small tin tube capped with wax—a softener pin wrapped in oily cloth—and took out a second land-bone flute.

Sigrið raised her own; Kári settled the lantern on a ledge and braced the basalt wedge where she pointed. “Listen,” Sigrið said, and Barbra did, the way she had listened to old chain-dance songs in Tórshavn and the church’s warning to turn back but sing. The three notes were not identical; they were cousins. They braided and parted, then slid over each other until the chamber’s hum thinned to a single shimmering thread.

They began. Leivur’s note rose clean and straight, the wooden seal warming to his pitch. Sigrið’s bone flute found the ribbed seal and coaxed it into vibration, an animal hush undercutting the human tone. Barbra did the oddest work of all—she sang a note she could barely hear and then stepped backward into silence at precise intervals, the wedge locking and unlocking with her breath like the blink of an eye.

The floor responded first, floating a fraction under their feet; then the walls flexed, and through the aperture they glimpsed movement: long racks on whispering rails, bundles slung in mesh that glimmered like wet hair, the archive slipping itself deeper beneath the hill. Water roared somewhere else, permitted, not invasive, and the sea’s backward walk passed like a giant hand brushing by the outside of a drum. When it was over, the chamber let go of its held breath. The three rosette seals dimmed, the last shiver of resonance melting back into stone, and the racks were gone into the further dark where even keepers were stingy with their lanterns.

Leivur sagged against the curve of the wall and laughed once, a single, startled bark that sounded like relief scraping the throat on its way out. “The equinox passage is set,” he said. “No shudder. No fracture.” Kári wiped his mouth, suddenly older, and shot Barbra a sideways look that had something like apology salted into it.

The air warmed by the heart-stone made the chamber feel almost human. They did not open a single scroll or unstopper a single tube, and that felt right to Barbra, who had pried open countless things in countless places and learned when to sit on her hands. Sigrið touched her sleeve, her grip small but sure. “You will write nothing that leads the wrong ears here,” she said, not a question but a careful trust.

Barbra nodded, the willingness to be bound surprising her with its ease. “I came for the hum and the old geometry of it,” she said. “That’s enough.” Sigrið smiled and reached into a niche that had been scraped clean by time. She brought out a disc the size of a palm, basalt incised with the six-petaled rosette, its edge cracked, its center polished to a satin by years of fingers.

“Retired,” she said. “A tuning disc spent in your service tonight. It is fitting that you keep it.”

Barbra turned the disc over in her hands, feeling the little star bite into her skin, and an ache moved behind her sternum at the thought of her glass wall cabinet at home. She pictured sliding this relic between a jade bead from a Burmese river and a terracotta shard from a Saharan caravan way, the Faroe basalt glowering companionably among a chorus of other mysteries.

She would tell the story to anyone who wanted it—the parts that were hers to share—about hums and valleys that sing twice and the way silence can be as active as sound. Kári clapped her shoulder, rough and shy, and Leivur dipped his head like a boy who wanted to be a man without forgetting the difference. They began to reseal the apertures and set the baffles to their quiescent stance, the work of putting a secret back into its coat. When they climbed up through the church’s hidden stair, night had settled over the valley and the sky had opened just enough for a smear of stars to show their faces.

The air was a salt-cold brush on skin, and the turf smelled of sleep. Barbra’s freckles prickled in the chill, and she tucked the disc into the inner pocket of her jacket, feeling the reassuring flatness against her ribs. In the cottage, she stood by the glass cupboard where the vellum had hidden, the room inhabited by shadows and her own steady breath. She thought of her grandparents—how they had taught her to do things alone and how she had learned, slowly, carefully, to carry other people’s trust as if it were her own.

Morning came like a tide that forgets it is supposed to turn. Barbra laced her Asics and walked the shoreline one last time, letting the waves carve at their private geometry while the houses of Saksun watched without speaking. Ragna was there on the path, her ellipses of speech wrapped in wool, and she nodded at Barbra in a way that felt like a ceremony. “You found only what you needed,” Ragna said.

“And left the rest.” Barbra smiled and pulled her jacket tighter, resisting the absurd urge to tell the woman she didn’t need makeup to walk into a legend and then thought better of the mirror she never liked. She said her thank-yous, which were both too much and not enough, and they agreed to leave each other’s names untroubled. On the ferry later, the islands collapsed behind her into sheep-dotted memory, then into the gray tenderness of distance. She opened her bag and touched the rosette disc again, the basalt warm from her body, a modest moon she could carry in her palm.

The quays of Tórshavn and the chain-dance hall rose in her mind; a flash of her Louboutins and a tumbling laugh from a night she had allowed herself to be someone with time. The truth was she fell in love easily—with people, with places, with the unrepeatable note in each—and this time, for once, it felt like the place had loved her back without asking too much in return. She leaned on the rail and let the wind unspool her thoughts into simple thread. When she reached home, she stood before the glass wall cabinet for a long time, the room quiet enough to hear the radiator tick and the old pipes hum like an embarrassed cousin of the fjord.

She set the basalt disc in its new place between the jade bead and the terracotta shard and watched the rosette settle into a conversation older than her own impulse to go, go, go. It did not reveal anything it was not meant to reveal; it did not need to. The mystery remained where it belonged—under turf, under ideas, under the careful guard of families who understood that some things live best beneath the tongue. Barbra exhaled, a long, contented breath, and felt the odd luxury of relief as the day, the adventure, and the note beneath the silence finally came to rest.