CHAPTER 4 - A Song That Lies

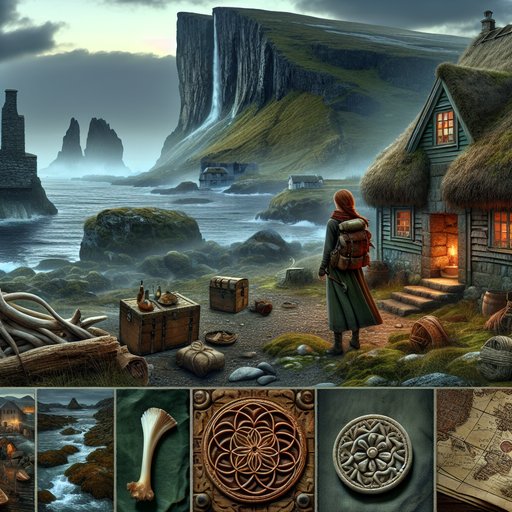

At ebb tide in Tjørnuvík, Barbra returns to the barnacled rosette and uses the remembered phrase to sing against the fjord’s hum. The seam opens, revealing a narrow passage and a scalloped acoustic chamber with a stone plinth. A small resin-sealed box inside contains a bead and a riddle: “When the sea walks backward, the valley sings twice. Bring the bone not from sea.” Interpreting this as a sheep’s bone, she fits one into a second rosette and sings again, only to discover a dead-end decoy marked with the warning to turn back. Frustrated but undeterred, she resolves to start over and seeks out Ragna, who admits the rosette is often a ward to mislead outsiders and hints the true gate is above the tide, where the note climbs. Recalibrating, Barbra hikes the cliffs, tests echoes, and realizes the “valley that sings twice” likely lies inland at Saksun. At dusk she faces away from the sea, sings toward the valley, and finds an upside-down rosette on the church lintel as a deep mechanism stirs beneath the turf, just as a shadow moves—someone, or something, is already there.

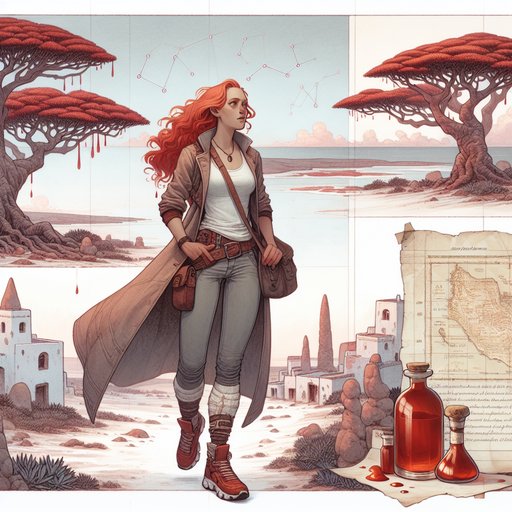

The seam she had awakened the night before waited like a held breath in the stone. Ebb tide dragged its cold skirts over the black sand of Tjørnuvík, hissing as the surf rethreaded the shore. Barbra stood in her tight jeans and tank top beneath her black leather jacket, blue-and-white Asics planted on slick algae, red hair pulled back from the salt wind. Her freckles, which she hated noticing in reflective patches of tidepool, were dusted with mist she refused to wipe away.

The hum rose again, a cello note emerging from the gut of the fjord, and her pulse matched it in the soft of her throat. She spread the vellum on a flat rock, aligning the six-petaled rosette with tidal notches inked in a hand centuries old. The phrase from Kirkjubøur perched on her tongue—turn back, but sing—and she let it spill in a steady line, tuning carefully to the sea’s low note until her breath found the same register. The carved rosette quivered, a darker vein running from petal to petal, and a hairline seam grew to the width of her finger.

She shouldered into the stone, slim muscles from years of long walks finding their usefulness in the grind of basalt. Cold air breathed from within, tinged with brine and kelp as the slab shifted with a damp, reluctant sigh. She slid sideways through the gap, conscious of the slick drip that traced her neck and the way the rock licked her jacket with chill. The passage was narrow, a windpipe in the cliff, and its walls glittered where salt had crystallized like a thin frost.

She thought of her grandparents’ quiet farmhouse in the evenings, the way she had taught herself to enjoy silence after the crash stole her parents when she was four; being alone never felt like lack, only a chance to listen. She moved forward without hesitation because that was how she had learned to move—decisively, even when her heart stumbled and her freckles burned hot with nerves. The hum thickened as she descended, resolving into threads that trembled the air like spider silk. The corridor spilled her into a chamber shaped by sound—scalloped walls cupping and throwing her breath back to her, an architecture of whispering bowls.

At its center sat a stone plinth with the rosette etched in deep relief and a shallow depression like a sleeping palm or an absent tooth. She placed the kelp-tied whalebone token in that cup, bones talking to bones, and sang the line again. Something in the stone answered not with words but with a shiver that loosened mortar; a lid in the plinth edged itself open with the smell of tar and seaweed resin. Inside slept a little box, its seams sticky with ancient pitch and the patient pressure of centuries.

The box yielded to her careful pry, a quiet pop, and inside lay a narrow strip of oily vellum wound around a carved bead of some pale horn. Ink lines shone where the damp had kept them whole: When the sea walks backward, the valley sings twice. Bring the bone not from sea. She held the bead, light and warm against her palm, and felt the thrill of a new insight lightning her chest.

The vellum’s margins carried the same rosette seal, but one petal was pricked—perhaps to indicate the time. Bone not from sea meant sheep, she thought instantly, in a place where whales and fish named the days. A valley singing twice was an echo, not a place like Tjørnuvík where the sea bellowed over everything. She clambered back into daylight and moved, driven by the clarity in her mind.

The beach climbed into turf and the footpath veered toward cottages, and she tracked a low fence to a midden where old bones weathered in a heap like chalk pebbles. A man in a blue cap watched her from a stable door and said nothing, but when she asked for a sheep shank, he gestured with two fingers and turned away. She cleaned a weathered bone on her jeans and hurried back to the gate, whalebone token in her pocket, heart tapping the beat of the chain-dance she’d heard in Tórshavn. This was the kind of hinge she lived for—an odd angle that made the whole door swing open.

The sheep bone fit the depression with a hollow snugness as she’d imagined. She sang the phrase a third time, pitch coiling around the briny hum until the chamber itself began to hum back at her. Stone ground behind the plinth, and a waist-high seam revealed itself in the far wall, then yawned just wide enough for a slight-bodied person to slip through. Joy flushed her cheeks—contracting in the freckles she loathed and forgot all at once—and she shouldered into the new aperture, mind racing ahead to what lay within.

The air grew colder, the salt-smell replaced by earth and something older, like old books sealed in a trunk. The passage doglegged hard and then stopped, abruptly, with the finality of a slammed drawer. A second rosette had been carved at eye level, and beneath it, in shallow letters, the Faroese words: vend aftur. Turn back.

She sang out, testing for a hidden seam, but the echo came thin and mocking, bouncing off some cunning curve that made her own voice laugh at her. Heat rose up her neck toward the hair she had twisted in haste, and for a breath she was furious at herself for trusting the obvious. The bead went back into her pocket: not a trophy yet, she told herself, but a reminder not to mistake any door for the right door. She sat on a boulder with her knees hugging the leather and stared at the vellum and the driftwood etchings spread on her lap.

The tide notes shifted in her gaze, not a schedule so much as a score; she traced the rosette petals and realized the pricked petal on the new strip didn’t match today’s ebb at Tjørnuvík. The “sea walks backward” could mean the dramatic retreat of the lagoon at Saksun, not the steady tug here. Her ears, always listening, caught the hum thinning on the wind as if it were slipping inshore along an invisible canal. She closed her eyes and let go of the tunnel she’d just failed, starting over the way she’d taught herself to, without shame.

She found Ragna at her door, lamplight making a buttery island in the gray. The older woman’s rosette brooch glinted and then turned, as if her shoulder rejected it in the current of their shared secret. “You walked where you shouldn’t,” Ragna murmured, not unkindly. “Those rosettes—you think they are keys.

Often they are wards. We turn away what we cannot trust.” Barbra met the warning with the quiet of someone who had learned to look people in the eye even when her heart skittered, and Ragna’s mouth softened. “If you listen with care, the note climbs. The gate you want is not under water.

Follow the birds when the tide falls.”

Barbra climbed, because the suggestion of a direction was worth a thousand warnings. The path cut along cliffs that rose like the pipes of an absurd organ, the wind ringing small notes out of the grass like fingers on strings. She cupped her hands and sang into a cleft, testing the scale, and was startled to hear her syllables answered twice in delicate succession—once from her left, once from above. Twin echoes.

She studied the vellum again, the tide marks arranging themselves like moon phases across relief lines she had ignored. If a valley could sing twice, it would be a place shaped to cradle sound, a place like Saksun, where the lagoon narrowed and the amphitheater of green threw the wind back on itself. Dusk had settled by the time she crossed the turf to her cottage, the hum now a teased string in the valley rather than a rope in the sea. The glass-fronted cabinet caught her eye; she let it, just for a heartbeat, imagine this bead one day nestled among the careful trophies of places where she had proved to herself she could go alone and return whole.

She swapped the black leather for a floral denim jacket to shake the cave out of her shoulders, scraped a pebble of kelp from her Asics, and tied her hair high in a functional knot. She’d never needed makeup to face a question, and the freckles she disliked were the same freckles that had soaked up a hundred strange suns. She slipped the whalebone token and bead into her pocket with the vellum and stepped into the blue hour. At the lip of the lagoon the tide was walking backward, the water drawing itself out of the bowl in a soft rush that bared the sandbanks in shining ribbons.

The hum lay low and wide, not a threat but an invitation for any voice brave enough to join it. Barbra stood with her back to the sea and faced the valley, the little stone church crouched to her left like a listener. She sang the phrase again, softer this time, and the valley answered with a doubling sigh that made the hairs on her arms lift. There, above her, in the shadow above the church door, she found a faint, upside-down rosette carved into the lintel.

The ground did not open in front of her this time; instead something far beneath her boots thunked, a deep wooden sound like a beam pivoting, and she felt the turf shiver through the soles of her sneakers. A tiny pebble skittered down a cut in the hillside, then another, and the hum slid a half-step higher as if answering a question she had only just learned to ask. The direction of the sound shifted, pointing not to the lagoon but toward a dark fold in the grass that no tourist trail marked. A shadow peeled away from that fold and moved, just a little too smoothly in the gloaming to be a sheep.

Was someone already waiting at the true Song Gate?