CHAPTER 3 - Sing to the Stone

Blocked by an inert rosette carving beneath the Tjørnuvík cliffs and a village bound to silence, Barbra hits a dead end. A kelp-tied whalebone token carved with the warning “turn back” and the persistent, taunting hum offer no forward path. Choosing to step away, she dresses up to go out in Tórshavn, allowing herself a rare night of ease and quick, ephemeral flirtation. At a small harbor hall, a traditional chain-dance song mentions the Song Gate and a bone key, and the melody fuses in her mind with the fjord’s hum. Later, a hint leads her to a church in Kirkjubøur where she notices a six-petaled rosette motif and a carved phrase that translates as “Turn back, but sing.” She realizes the tides alone won’t open the way; the gate responds to resonance, perhaps a human voice aligned with the sea’s low note. Returning to Tjørnuvík at the next ebb in her usual field clothes, she tests the idea: whalebone in hand, vellum aligned, she sings the remembered phrase against the hum. The stone quivers, and a seam darkens at the rosette. The chapter ends with Barbra poised on the brink, wondering if she has finally found the key or awakened something watching from within.

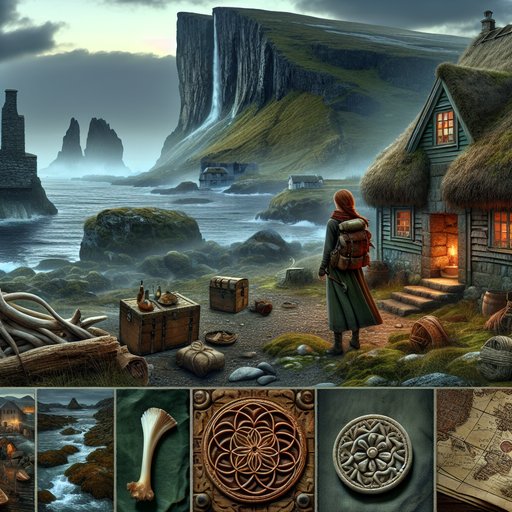

By morning, the cottage held the hush of a church, soft and complete, as if the walls had absorbed all the night’s whispers. Barbra sat cross-legged on the plank floor beneath the window, the vellum smoothed against her knee, tide notations flickering where the light touched them. The six-petaled seal stared up like an eye, indifferent to her calculations; the barnacled slab at Tjørnuvík had not budged the day before. Even the hum at dawn sounded like mockery—a low, patient vowel that came and went with the breath of the fjord.

She turned the kelp-tied whalebone token in her fingers until the salt stung, reading the Faroese etching again: turn back. It had to be more than a warning, she told herself, more than an old family’s way of closing doors. Yet the village had closed anyway: fishermen looked past her, boys were shooed away, and an elderly woman whose rosette brooch could have been a twin to the seal on the vellum turned her shoulder at Barbra’s quiet greeting. She had mapped the tide sets, traced the driftwood’s cryptic lines, and sat in the sea cave until the hiss of foam answered the hum; still, nothing.

If there was a key, it was not the kind that fit a lock. Frustration settled in her sternum like a stone of its own, heavy and chill. When she felt that old weight—the one she remembered from childhood nights after the accident, when she learned to do without asking—she chose the trick that had saved her more than once. She stepped away.

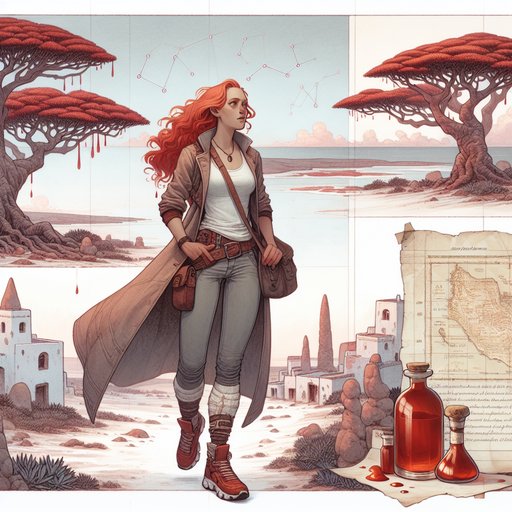

She showered the salt off, tugged her hair into a loose knot that did nothing to hide the freckles she hated, and left her face bare as always; she had never needed makeup, though she doubted it in mirrors. She pulled on tight jeans and a slinky black tank top, shrugged into a glittering jacket that caught the wet light like fish scales, and slipped her feet into a pair of black Louboutins she rarely dared bring near any North Atlantic street. She walked carefully down the cobbles toward the bus like a woman crossing ice, protective of the red soles she loved. Tórshavn in the rain was a film of slick reflections and yellow windows, gulls looping like scribbles across a low sky.

She found a small harbor hall that smelled of wool and coffee and old driftwood, where a fiddler tuned in the corner and people made a chain with their hands. Barbra let the rhythm find her—the stamped heel, the forward sway, the bright turn—and somewhere between the third and fourth verse, she forgot the slab and the watching eyes and the warning carved in whalebone. A man with wind-rough hands and a smile like a harbor lantern introduced himself as Andras; they laughed too easily, fell into conversation with the breathless intimacy of strangers. She felt that familiar tilt toward affection and, just as swiftly, the quiet braking of a life always already in motion.

They stepped outside at the break to breathe air thick with salt and sheep-lanolin and diesel, and he nodded toward her glitter jacket with a small grin. "You dress braver than most for this weather," he said, not unkindly. She looked at his knit cap, at the red slashes boats made across the harbor, and shrugged. "I’m careful when it matters," she answered, and he seemed to understand she meant more than shoes.

When she mentioned the hum, the vellum, the slab with the rosette, his gaze flicked away in a nervous habit that told her he knew more than he’d ever say out loud. Inside, the fiddler raised a tune older than any of them, and the hall answered with a low verse that made the floorboards sing. The song carried a line she had heard in last night’s shanty in Tórshavn, now sharpened by proximity: "Sing to the stone at ebb, turn the bone at the gate of song." A six-petaled rosette had been carved into the top of the fiddler’s instrument, delicate and precise, and the little pattern seemed to pulse with each note. Barbra’s chest hummed in sympathetic vibration; she felt the fjord’s low tone overlay the melody as neatly as a second hand laid over the first.

Not tides alone, her mind whispered. Tides and voice. After the dance, with the hall emptying and the rain softened to a mist, Andras stood with her beneath the eaves and said, "My grandmother told us stories to keep us small. But she also said, not all turning is retreat." He hesitated, then pointed south, thumb rubbing the seam of his jacket.

"You like old places? Go to the old church at Kirkjubøur. Sometimes the choir rehearses late, and the stones there carry sound strange, like the sea is listening." His eyes flicked to her freckles for the briefest moment, as if surprised by them, as so many were, and then away. She felt the tug of a beginning and let it go, gently, knowing she never stayed long enough to hold anything.

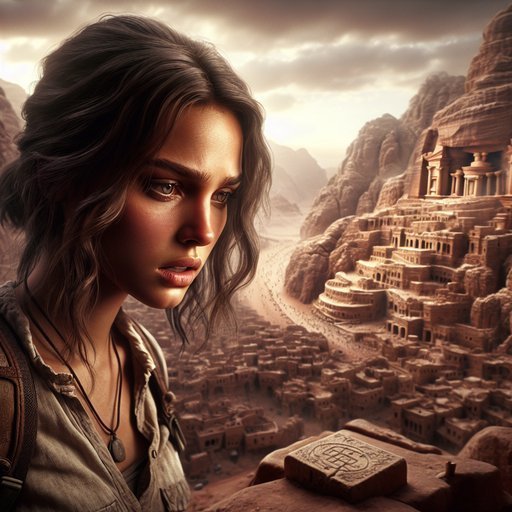

Kirkjubøur’s black-tarred roofs glistened in the drizzle, and the ruin’s arches framed a sky the color of pewter. Barbra slipped inside the church across from the ruin when the door cracked open to a murmured hymn, her red hair damp and curling at the ends. A handful of voices rose—women and men—soft but steady, and the room took their notes like a whale takes a deep breath, ribbed wood and stone making a second choir. On the end of a pew, someone long ago had carved a neat six-petaled rosette, and beside it, faint letters she traced with her fingertip.

Vend aftur, men syng—turn back, but sing. She pulled out her phone, photographed the carving, then stood very still with the whalebone token cupped in her palm. A thought clicked into place: the driftwood’s lines were not mere scratches—they had been erratic, but in clusters of five, like staves. The vellum’s tide marks were time signatures, the rosette a kind of throat.

She slipped outside after the final amen and struck the whalebone lightly against a railing; it gave a soft, clean note, near to the fjord’s hum. She remembered how her grandparents’ old radio would find a station only when the dial and her hand and the antenna agreed. Dusk was gliding in as she returned to the cottage and traded glitter for utility. She folded the Louboutins into their travel bag, set them on the high shelf where sea air wouldn’t reach, and laced her blue-and-white Asics with ritual care.

Tight jeans, black leather jacket, the whalebone token tied again with kelp and slipped into her pocket; the tank top warmed beneath the jacket as she walked. On the table, the vellum waited, its rosette dark as ever, and she laid it beneath plastic in case of spray, a field habit she’d learned on an Iceland glacier where everything was damp. She moved quickly without hurrying, the way you do when something fragile and precise has to align. At Tjørnuvík the ebb laid the stones bare and made the world larger.

She found the carved rosette beneath the cliff, scraped free the newest fringe of sea grass, and compared vellum to rock until the petals matched. When the hum rose from the fjord with the tide’s long exhale, she put the whalebone to her lips without thinking and sang the line from the hall under her breath. Her voice was untrained, thin in the wind, but the stone heard; she felt the undernote swell, the kind of resonance that passes through bones and memory. A faint seam along the rightmost petal darkened like damp cloth.

She stopped, breath caught, heart quickening, and sang again, this time lower, the way the choir had settled their chords into the nave. The seam trembled, almost imperceptibly, and a tremor carried into her palm from the rosette’s center, like the rumble of a truck through asphalt. Someone had told her to turn back; someone else had told her to sing; now both instructions braided into a single act—she angled her shoulders away from the sea, faced the cliff, and let the final phrase of the old song climb out of her throat. The whalebone turned easily in her fingers as if fitting a notch she hadn’t seen.

Was that the rock shifting under her hand, or something within answering at last?