CHAPTER 2 - The Silent Rosette of Tjørnuvík

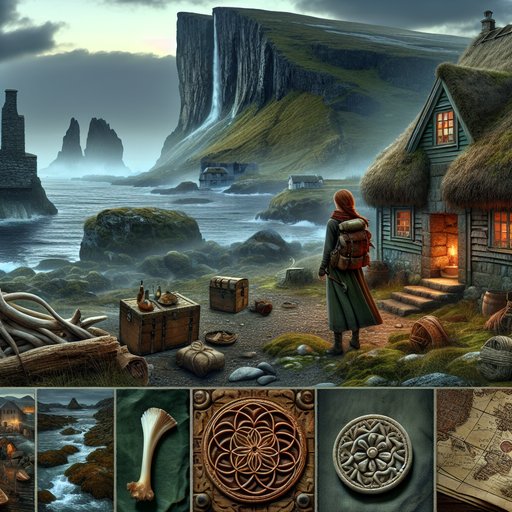

Barbra Dender follows the vellum’s tide notations to Tjørnuvík at ebb tide, wearing her usual jeans, tank top, and blue-and-white Asics beneath a black leather jacket. She finds her first concrete clue: a six-petaled rosette carved into a barnacled slab beneath the cliffs, aligned perfectly with the vellum’s markings, yet inert and unhelpful. Locals who clearly recognize what she is chasing refuse to assist; two fishermen warn her off, an elderly woman with a rosette brooch turns away, and even a curious boy is silenced. Barbra explores a narrow sea cave where the hum seems to grow, but the tide’s rhythm and the unreadable mechanism prevent progress. Back at her turf-roof cottage in Saksun, she studies the vellum and the driftwood, correlating notes and times, but she remains blocked. As dusk falls and the hum returns, someone leaves a kelp-tied whalebone token carved with the same rosette and the Faroese word for “turn back.” The chapter ends on a tense cliffhanger as Barbra senses she is being watched, the stones seeming to whisper her name.

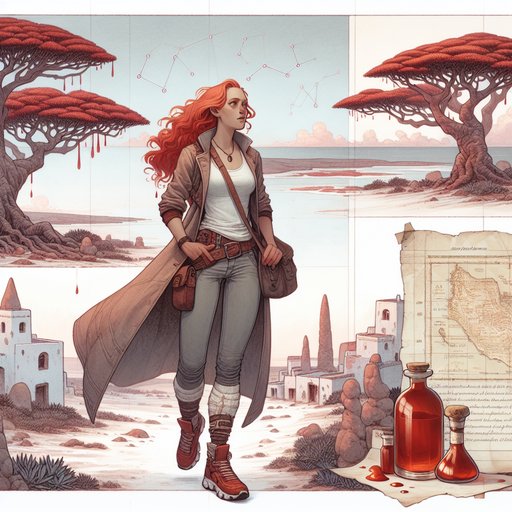

At first light, Barbra laced her blue and white Asics and shrugged into her black leather motorcycle jacket, the only glossy thing about her in the misty morning. Her tight jeans were still damp at the hems from the previous night’s shoreline prowling, and she rubbed absently at the freckles dusting her nose, wishing—as always—they’d fade. She wore no makeup, not needing it, though she never believed that when she caught herself in a mirror, a restless, red-haired stranger looking back. The wind smelled of kelp and rain as she left the turf-roof cottage in Saksun, the memory of that low humming still vibrating somewhere in her ribs.

Raised by her grandparents to rely on her own hands and choices, she walked out alone toward Tjørnuvík at ebb tide, tracing the vellum’s notations like a covert compass. Tjørnuvík unfurled from between the hills like a dark ribbon, its black-sand beach glistening under a gray sky, the basalt cliffs looming like organ pipes. Sheep watched her pass with dull curiosity, tinkling bells stirring a rhythm just off the beat of the sea. The few villagers she saw pretended to focus on nets and weathered skiffs as she approached, their eyes flicking to her jacket, to her hair, then away.

She lifted a hand in greeting and got a nod or the ghost of a smile, but nothing more. Even the gulls seemed to keep their distance, as if they knew better than to get involved. Barbra timed her steps to the vellum’s tide marks and the scrawled lines she’d memorized, turning where the fjord’s hum deepened into a drone. Near a tangle of wrack, the rock shelf dropped away into a pocket at the cliff’s base, slick with fine algae.

There, partially submerged as the sea sighed in and out, the stone bore a carved rosette—six petals incised with a sure hand, worn smooth by untold seasons. Her breath caught, an electric thread pulling along her spine; this was the emblem sealed on the vellum, bold as a brand. She pressed her fingers to the stone and felt only the cold and the faint fizz of tiny bubbles bursting against her skin. The rosette didn’t move, didn’t click, didn’t sing; it just lay there, a centuries-old flower carved into basalt, sternly indifferent to her curiosity.

She wedged herself below the lip of rock, wincing as barnacles bit at her palms, and peered into the seam running beneath the slab. Kelp swayed like hair, a slow dance in green eddies, and tiny shrimp flickered in and out of shadow. When the water withdrew, she heard the hum again, a muted consonant held in a patient throat somewhere deeper in the cliff. It was not a key she could turn, not a door she could nudge; it was a clue that refused to become anything more.

Two men in oilskins watched her from the boathouse when she returned to the sand, their faces mapped with wind and work. Barbra smiled, the kind that had opened zippers and war stories in ports from Ushuaia to Uummannaq, and held up the vellum folded small in her hand. “I’m chasing an echo,” she said lightly. “A local one.

Do you know the old name for the cut under that west cliff?” The taller man’s jaw shifted, and the shorter one spat sideways before replying, “We know tide tables and where a skiff won’t break a spine. The rest is weather and old words you don’t want.”

“I heard a shanty in Tórshavn,” she ventured, grafting casual to earnest. “Song Gate, they called it. I’m just a walker with a bad map and a stubborn ear.” The shorter man’s eyes softened for a blink, then went dull.

“The gate takes as it gives,” he said, as if conceding a pebble. “And it doesn’t give to strangers.” When she said Ragna’s name, the taller man’s mouth went thin, and he turned away to heft a coil of rope, conversation closed as neatly as a locked hatch. Barbra tried the community hall where a kettle steamed and the smell of cardamom drifted, hoping hospitality might soften reticence. A boy of twelve hovered near the doorway, elbows sharp as kites, and risked a whisper that sounded like “Sangportur” before an elderly woman laid a hand on his shoulder.

The woman’s brooch—silver, dented—the very six-petaled rosette, sat stern and shining at her breastbone. “Ebb’s turning,” the woman said, voice kind as a blanket and firm as a slammed door. “You’ll want to watch your footing, miss.” Barbra bought a cinnamon roll she didn’t taste and left with more sugar on her fingers than information in her pocket. By the time she reached the cliff again, the sea was sucking its breath in longer pulls, the exposed ledges cut with trickling rivulets.

She found a narrow crack lipped with weed, a slit that might once have been a crease in the stone before hands or time widened it. Sliding sideways, jacket scraping rock, she pushed her phone’s light into wet dark and followed it into a seam of whispering air. Inside, the hum gained a harmonic, a chord built from drip and echo, as if the cliff were a great throat singing to itself. A worn slab crouched at the back, circled by tidal etchings, the rosette faintly visible under a varnish of mineral and age.

She laid the vellum against the slab, aligning its sketched petals with the ghostly carving, and counted the beats between the sea’s billows against the stone. The rhythm on the parchment didn’t match what she heard; she was early or late by some arithmetic only the cliff knew. Her knuckles ached, tiny cuts burning where salt had found them, and she tasted metal on her tongue, the tang that always found her in moments like these. The hum was patient, the gate—if it was a gate—stayed sealed, and the water began to creep back, indifferent to her need.

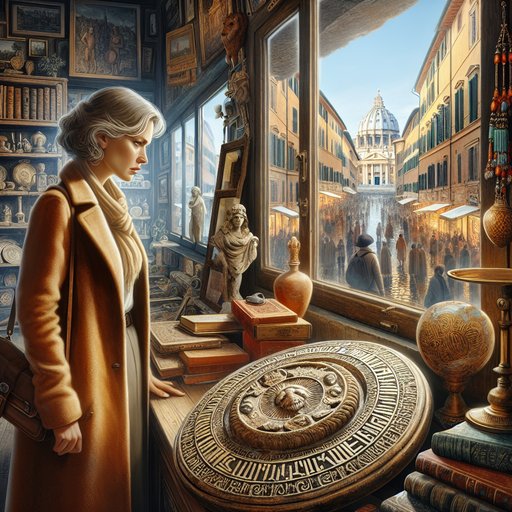

She retreated crabwise under the rock lip and sprinted the last yards across the wet sand, breath ragged, shoes gritted with black grains. Back in Saksun by late afternoon, she built a small fire and spread the vellum and the driftwood on the cottage table, weighting corners with a mug and a smooth stone. She sketched the rosette from the cliff, charcoal darkening the petals into a tidy six, as if repetition would conjure leverage. A fragment of the sea shanty threaded in her head, the vowels bending like rope under strain, and she murmured it into the room, listening for the hum to answer.

Her glass wall cabinet at home flashed across her mind—the artifacts kept behind quiet panes—and she smiled at how empty her hands felt when mystery refused to yield. She searched the cottage again anyway, fingertips probing seams behind the glass cupboard where she’d found the vellum, but found only dust and a splinter that left a sting. Dusk wheeled in slow as wool, and with it the hum returned, trembling in the wooden bones of the cottage, under the soles of her shoes. She charted the sound’s swell and fade, marked times and tiny notations in the margins of the vellum until the page was a garden of numbers.

She tried the song again, then whistled low, testing intervals, the way her grandfather had shown her to find a stubborn radio station on the old set. The answer, if there was one, waited in a crucial minute or an object not yet found, a missing tooth in a gear no one would let her see. The villagers had closed their lips; the rosette had shown itself and withheld its lesson; all she had was patience and the stubbornness she’d learned as a child who had no choice. A soft tap against the door broke her concentration.

Barbra stood, heart pitching, and opened to a gust of salt-sweet wind and a slick ribbon of kelp tied around the handle like a gift’s bow gone bad. Dangling from the knot was a smooth piece of whalebone, pale as milk, carved with the six-petaled rosette and a single word scored deep: Vend. Turn back. She stepped into the yard, breath fogging, and saw the faintest smear of wet footprints vanish into the night grass as the hum rose again, vibrato rich enough to feel in her throat.

The token was no help, a warning in another language that did nothing but confirm what she already knew—people here knew this secret and meant to keep it. She turned the whalebone over, feeling the grooves with her thumb, and the cottage’s timbers murmured in sympathetic resonance, making the rosette’s petals seem to shiver. Somewhere beyond the hills or beneath them, stone sang to water in verses older than any shanty, and she realized she was no longer entirely alone with her questions. A shape shifted at the corner of the yard, more suggestion than person, and the hairs on her arms lifted as if the hum had reached for her name.

Who had come to her door at dusk, and why did the stones sound as though they were waiting for her to answer?