CHAPTER 1 - The Blue Sun over Suðuroy

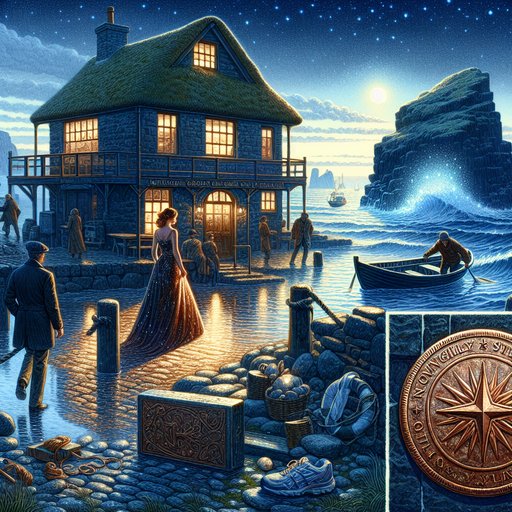

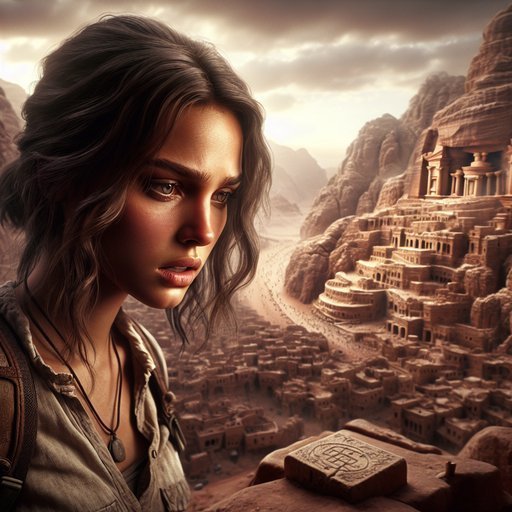

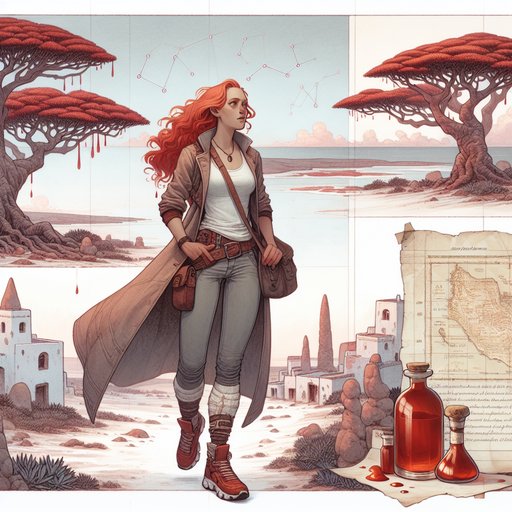

Barbra Dender, a 31-year-old red-haired traveler raised by her grandparents and known for chasing unusual mysteries, arrives on Suðuroy in the Faroe Islands. Staying in a turf-roof guesthouse above Tvøroyri harbor, she sets out in her tight jeans, blue and white Asics, and a leather jacket to explore the austere cliffs and sea-scalloped coves. Locals hint at a phenomenon they call the Blue Sun—a strange cerulean halo that blooms near a sea stack at dusk—and their guarded hush only deepens her curiosity. Spotting motifs that echo an artifact in her glass cabinet at home, she senses a long-kept family secret. That night, beneath loose floorboards, she discovers a salt-crusted copper disk etched with a starburst and the word BLÁSÓL, alongside faint marks like coordinates. As wind rattles the window, someone slides a note under her door warning her to seek a “singing cave” at slack tide and to bring no light. The chapter ends with Barbra holding the disk and a question—who knows she’s here, and why do these clues converge on a hidden cave?

The day Barbra Dender flew north, the sky looked like a strip of wool pulled long, gray and soft, and she decided it was exactly the right kind of sky to carry a secret. She zipped herself into a black leather motorcycle jacket over a slate tank top, tight jeans hugging her hips, blue and white Asics laced tight for whatever the islands demanded. Her red hair frizzed in the damp air of Vágar’s tiny airport, freckles—those constellations she’d never learned to love—dusting more boldly across her nose in the diffused light. She carried only what she trusted: a weathered backpack, a dog-eared notebook, and a will sharpened by years of traveling alone.

Somewhere on the far side of the ferry, she told herself, something old would look at her and blink. She had chosen the Faroe Islands because a photo had teased her from an obscure maritime blog: a ring of blue light skimming a black sea, captioned in a language she couldn’t read. Suðuroy, someone wrote in the comments—south island—off the tourist maps, less visited, stern. That was invitation enough.

She rode the ferry south with fishermen who smelled of salt and ropes, the engine thudding through the floor like a second heartbeat. As the bow rose and fell, cliffs slid into view, and she felt the small, familiar pride of being exactly where she wasn’t supposed to be. Her lodging was a turf-roof guesthouse perched above Tvøroyri harbor, the grass on its roof combed by the wind, the windows salt-flecked and low. Inside, the boards creaked like ships, and someone had placed a whale rib along a shelf as if it were a guardian.

Her room was spare but bright: a narrow bed, a deep window seat that framed the harbor, and a hook where she hung her jacket to drip. She set her backpack at the foot of the bed and ran her fingers along the sill, feeling the old paint bump beneath her fingertips. This, she thought, was a place that knew how to keep its mouth shut. At home she had a glass wall cabinet filled with the stories that had kept her company: a jaw harp from a Mongolian steppe, a clay spindle whorl lifted from a desert ruin, a green shard of bottle glass that had once caught moonlight on a Portuguese cliff.

She could stand before them for hours, feeling her grandparents close—together they had taught her to mend and to reuse, to find answers in quiet. She’d learned to be alone after the car accident took her parents when she was four, and it had sharpened her hearing for silences that meant something. This trip had an empty shelf waiting; she’d left just enough space for a thing whose name she didn’t yet know. She touched the vacant gap in her memory and let it widen into hunger.

The wind carried a sea-raw bite that deepened as she stepped back outside, the village below stitched together by wet streets and boat sheds. She liked how walking could be an argument with herself; her legs, slim and slightly muscular from miles and miles, settled into stride along the road to the headland. Black basalt rose where the world had cracked, the cliffs like broken teeth, and fulmars traced the seams of the air with tireless wings. The grass was a stringent green, cropped low by sheep that regarded her with square pupils and then returned to their chewing.

When she reached the path’s end, the island fell away in a laugh of height, and the Atlantic laid its hard blue hand down on the rocks. She looped back through town by way of the wharf, where men in oilskins hauled nets and shook out their shoulders the way sailors do when the day asks for more. An old man with a scar across his cheek hummed in a minor key, a tune that felt like mist. When she asked about a blue ring on the sea, his humming stopped and he shrugged, the motion tiny, like a bird refusing to be seen.

“Blásól,” another fisherman said, the word clipped and secret, and then he turned away as if the syllables had cost him something. Barbra filed the sound of it in her head, an echo waiting for a wall. Dusk in the Faroe Islands came like ink finding paper: all at once, clean and purposeful. She stood at the viewpoint above a sea stack shaped like a waiting knuckle and watched the water begin to gather light where no sun was.

It was not phosphorescence; she knew that grainy, ecstatic spark from nights on warmer coasts. This was a smooth, cold flare, a disc the color of a bruised sapphire that hovered below the surface, racing its circumference in a slow circuit. It should not have been beautiful, because it was wrong, and that was part of why it was. Something in her opened at the sight of it, that seam that she had learned to split on command—fear a distant, ridiculous bird that did not deserve her attention.

A wind gust lifted her hair and cudgeled it into a copper pennant; her freckles prickled in the chill, and she found herself wanting to hide them even as there was no one to impress. She didn’t wear makeup on trips like this because there was nothing it could do against the weather or what she wanted. She felt, without words, the texture of a long-kept promise in the air, and the lullaby of her grandparents’ old farmhouse hummed in her ribs. The blue light lilted, and she knew she would take whatever path it offered.

Back at the guesthouse, the hostess introduced herself as Rannvá and poured tea that tasted of smoke and sweetness. Family photographs along the hallway showed women with robust shoulders and eyes like wet stones, and one of them wore a shawl stitched with a starburst motif Barbra recognized from somewhere she couldn’t place. Rannvá’s husband, Karl, had the weather in his face; he nodded at Barbra as if he knew she’d come to pry a lid loose. “Weather turns quick,” he said, which was exactly the sort of non-answer that told her everything and nothing.

Barbra carried her tea to her room and let the door click shut behind her. She took out her notebook and roughed a sketch of the sea stack and the position of the blue halo, marking the time and the color as if they could be pinned like moths. The quiet had a music to it—gulls outside, the gutter cleaning the roof, the small gossip of wood contracting in the cold. She thought of the glass cabinet at home, the city light breaking over it in the morning and making her hoard look like a small museum to a life no one else had needed.

She thought of the lovers who had come and gone, who had called her beautiful and then tired of her leaving, who had not understood that the itch at the base of her skull wasn’t a person she was missing but a missing edge to a map. In the corner of the room, a thin crack in the floorboard widened, and the wind made a sound in it like a whistle. Night grew thick, and she shrugged on her floral denim jacket for a walk to the harbor pub, because she wanted the sound of voices to measure her questions against. The pub smelled of peat smoke and fried fish, the tables crowded with work-wear and tired laughter.

She kept mostly to herself, listening as a pair of teenagers argued in Faroese and English about something they called the Night Singers. “Not a choir,” one scoffed when she asked with a laugh, “a family.” The other glared and tugged his friend away, and in that tug she saw a seam of fear stitched tight. She finished her beer and slipped back into the cold, the black path home bright with wetness. A cat glided out from under a truck and considered her, then vanished, a gray lozenge in the dark.

By the time she reached her room again, her hands had gone numb and found warmth slowly, tingling against her own skin. She hung her jacket and rubbed her arms, exhaling a stray note of satisfaction. The window rattled as if someone wanted in, and she told herself it was the wind having its say. The loose floorboard was a question she finally couldn’t ignore.

She crouched, slipped her fingers into the crack, and felt the old wood give with a reluctant sigh as if it had been waiting only for the right insistence. Beneath the plank lay a square of oiled linen tied with a knot that had hardened into itself, and the salt smell rose as if the sea had been rehearsing down there. She worked the knot with a nail and patience until it yielded, then unrolled the cloth on the bed’s white blanket. Something round and heavy dusk-lit the air between her bones.

It was a copper disk the size of a small plum kept flat, crusted with verdigris and salt, the metal pitted and lovely, as if the sea had licked it for a century and grown fond of it. Around the edge ran a pattern like a sixteen-point star, cleverly uneven, and at the center, where the green flaked thinly, she could make out letters. BLÁSÓL, it read, in a hand that had been both careful and impatient, and beneath it a ring of dots and shallow claw marks that looked like someone had translated numbers into symbols. On the back, two initials had been fussed into a corner: S.S., as neat as a schoolchild’s.

She found that she was holding her breath as if breathing would dim the disk. Some memories rise whole, and in her mind she saw the bronze coin she kept at home from Orkney, stamped with a starburst just off-square, as if the person who struck it had been jostled by the world. The match wasn’t exact, but it was kin, and that kinship made the hairs along her forearms lift. She was suddenly certain that whatever she had found here had roots that threaded under the Atlantic like old phone lines.

She wiped a thumb across the copper gently, just enough to coax a clearer line from the corrosion. A pale coordinate glimmered up through the green: 61° 31'. Something. She sat back and glanced at the window out of habit, the glass a black mirror, her face ghosted into it with her freckles like powdered ash and her mouth a stubborn line.

At that exact moment, knuckles tapped the glass softly—twice, then once, the way a person knocks when they don’t want to be sure. Her heart strobed hard, and she stood, the disk tucked into her palm, moving to the window with care. Outside, there was only her reflection and a curl of blown sea spray; no face, no hand. She exhaled and told herself not to romanticize the wind.

Then paper hissed along the floor, and she turned. A folded note had been shoved beneath her door, the edges damp, ink blotched where a drop had landed and been absorbed. She knelt and opened it, hands steady the way they became when she felt closest to the thread she chased. The message was short, written in an elegant, old-fashioned hand: At slack tide, the cave sings.

Bring no light. She read it twice, then again, testing each word on her tongue as if flavor would reveal intent. She looked back at the disk and saw that the shallow marks around the edge could be read against a tide table if someone had taught you how, each dot a hush in the tide’s pulse. Her grandparents had always said that the sea could be counted if you listened with your hands, and she could almost feel their fingers guide hers to the right hour.

The initials S.S. leapt at her as if someone had whispered them, and she wondered if this was a person still walking the island or a bone whose name had persisted longer than the bone itself. The blue sun at the sea stack, the quieted fishermen, the Night Singers—her mind threaded them like beads into a pattern that wasn’t yet a picture. She put the disk back in its linen, then slid it under her pillow as if it were a dream she was keeping warm.

The wind tried the window again and then let it be, and the old house exhaled a sound like a ship giving the sea what it wanted. She pulled her tank top straight, dragged on a different jacket—this one a floral denim softened by years—to check the harbor clock and mark the slack tide. Outside, the village was a smudge of light against the black, the harbor lamps trembling long on the water. She walked to the edge of the quay and looked toward the dark line where the cave mouth would be if the map in her mind was honest.

“No light,” she murmured, and felt the shape of that instruction in her own throat. When she returned to her room, she sat on the bed and forced herself to breathe in slowness, counting her breaths to keep the horses of her thoughts from bolting. Her freckles felt electric as if each one had been pricked awake by the sea’s static, and she thought, absurdly, of the Louboutins wrapped in their dust bags at home—bright, delicate, not made for this. The copper disk waited under her pillow, steady as a metronome she couldn’t hear.

She turned the note over, seeking a second line that wasn’t there, a signature, an afterthought. Who had slid the warning under her door—and why did the copper disk point her toward a cave that sang?