CHAPTER 1 - The Humming Fjord

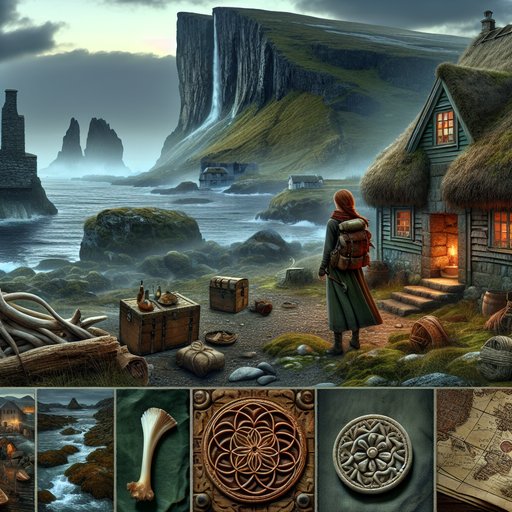

Barbra Dender, a 31-year-old red-haired traveler raised by her grandparents, arrives alone in the Faroe Islands to begin a new journey. Renting a turf-roof cottage in the sheep-dotted village of Saksun, she quickly notices a strange low humming that seems to rise from the fjord at dusk. Intrigued by the phenomenon and the wary hints of a local woman named Ragna about old secrets guarded by families, Barbra explores the shoreline and finds driftwood etched with cryptic lines. After a night in Tórshavn, where a sea shanty mentions a place called the Song Gate, Barbra discovers a hidden vellum behind a glass cupboard in her cottage. The vellum bears a six-petaled rosette seal and tide notations that align with the humming. Ragna reluctantly points her toward Tjørnuvík at ebb tide, and Barbra realizes she has her first clue: the hum, the tides, and the vellum together indicate an entrance concealed beneath the cliffs. She sets out determined to follow the sound.

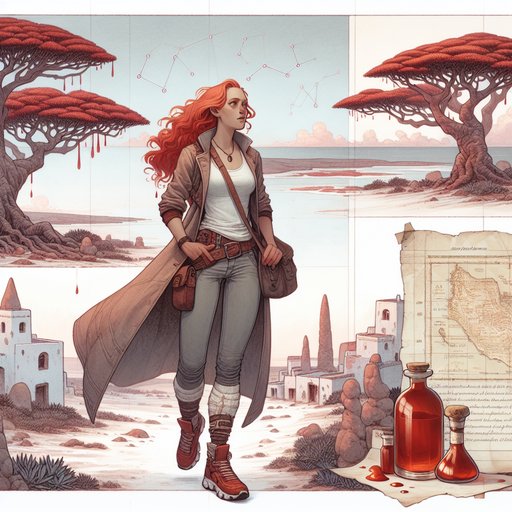

The prop plane skimmed low over waves the color of forged iron, the Faroe Islands rising from the Atlantic like the vertebrae of some sleeping giant. Barbra pressed her temple to the window, a haze of freckles across her nose catching the watery light, her reflection a reminder of the face she rarely fussed with. She wore tight jeans, her blue and white Asics sneakers, and a white tank top beneath a scuffed black leather jacket she had stuffed into her backpack, because here the weather turned on a breath. Her red hair, unashamedly unruly, lay in a loose braid that the plane's stale breeze couldn't tame.

She hadn't been here before, and the way the cliffs shouldered up against the sky told her this place would not pretend to be something it was not. At thirty-one, Barbra had learned to prefer that in people and places: unvarnished truth, raw edges, less polish and more marrow. Her earliest edges were honed when her parents died in a car accident and her grandparents took her in, teaching her to make tea, mend a seam, and keep one's own counsel without growing cold. She had taught herself long, solitary walks until the muscles along her thighs were corded and patient, the kind that carried her down roads few tourists considered.

She didn't wear much makeup, didn't need it, or so her grandmother had always insisted, while Barbra only ever saw a freckled face she wished the sun would spare. Home was a small apartment with a glass wall cabinet full of trophies from other mysteries, each one pried loose with care from families who trusted her because she did not break things to see what's inside. She rented a cottage in Saksun, a village strung around a lagoon like buttons on a green coat, the hills tufted with sheep and roofs that grew grass like brows. The key was under a flat stone by a low black door, just as the message had promised; inside, the place smelled like salt, peat, and wool.

A single room sank around a table and a narrow bed, a stove with enamel chipped like old teeth, and, tucked against the wall, a glass-front cupboard holding cups and an empty shelf. The empty shelf made her think of her cabinet at home and the habit of leaving space for the thing she hadn't yet found. She set down her pack, her sneakers whispering on the scrubbed floor, and leaned toward the small window where a soft veil of mist ascended the valley. Even before her bag's zipper had settled, she heard it: a hum at the edge of hearing, the valley singing in a pitch that didn't belong to wind.

It was a low, patient sound that seemed to come from the water itself, from the way waves stroked the long arm of the fjord and threw their voices back from the basalt. The sheep stopped chewing for a heartbeat and lifted their heads as if they too were counting. Barbra stood with her palm against the cool windowpane, feeling a vibration she couldn't measure, an itch beneath the skin more than beneath the ear. She had chased thunder in deserts and whispers in forests, but this was the first time a stretch of water had greeted her like a tuning fork.

She found Ragna by the door of a weather-darkened shed, a woman the color of peat, all knit layers and blunt hands and eyes the gray of a storm when it is deciding. Ragna gave Barbra the precise welcome one gives to any stranger who steps anywhere near a family fence: neither smile nor frown, but a weighing. Barbra introduced herself, explaining that she kept to the paths and that curiosity in her case came with care, not plunder. Ragna snorted softly at that and said, in the kind of voice that dislikes being overheard, that the fjord had been humming long before tourists learned to stand on cliffs and take pictures of falling water.

'Some say stones breathe here,' she added, as if to push Barbra away with nonsense, yet her eyes didn't quite let her go. Barbra went along the shore where the green fell away to pebbles, the water low and laced with kelp that swayed like wet hair. Her Asics left neat marks on the sand and her jeans turned darker up to the knee when a spray reached her and shrank away. She found a length of driftwood, its pale belly carved with a pattern of crossed lines and a small six-petaled rosette at the end, so faint she had to tilt it toward the gray light to see.

She ran her thumb over the etching and felt the impulse to slip it into her bag; the museum of her life had begun with a pebble, then a coin, then a wooden bead, each of them taken with permission or abandoned when permission could not be obtained. This piece she left where it lay, and instead she took a picture, flowing back from it like the tide. At dusk, she unpacked her bag methodically, the ritual that said she was at home wherever she set her shoes and folded her jacket. She had brought one pair of Louboutins in an old cloth bag, a habit of tenderness; if she went out somewhere with a proper floor, she'd wear them with jeans and a jacket, careful as if cradling glass.

Her jackets were an indulgence she could afford—leather, denim, floral, glittering—some of them stains of memory from deals struck and letters read, each a different posture for the same spine. She caught her reflection again in the window, the constellation of freckles she disliked showing like stars before rain, the natural glow of her face that her grandmother would have patted with approval. The hum was back, perhaps louder, perhaps she had simply tuned to it, and she lay on the bed with her fingers steepled, listening until the sound sifted into her bones. Morning made the hills look like a green sea had frozen mid-wave.

Barbra took the high track, her stride steady, breath in even pulls, shoulders easy under a faded floral denim jacket that had survived more countries than some passports. The sound was absent under the brightness, and when it returned, a thin thread at first, it waxed with the tide. From the high ridge she saw a dark cut on the far side of the bay, a cave where the surge lifted and fell like a lung, and when the water bellowed, the tone rising when the swell withdrew, she made notes in a small weatherproof book. She drew a rough map, arrows marking the places where the sound seemed to pivot, numbers scratched beside them with the caution of someone who knew tempo mattered.

The next evening she took a bus to Tórshavn, the capital in miniature, houses as neat and braced as sailors in formation, tiny lights pricked along the harbor. She dressed in her jeans and a black leather jacket, sliding her feet into the red-soled heels because her body remembered the lift and balance of them, the way they changed her pace. In a low-ceilinged bar, where the smell of fish and smoke sat like stubborn guests, a group of men sang in Faroese about a gate that sang back at those who dared knock. One had the windburned face of a man who had wrestled with line and oar all his life, and when his eyes tipped toward her, something warm tugged and then let go—the kind of swift, shy pull she knew would burn out by dawn.

She listened, learned that locals once called a notch in the cliffs the Song Gate and that some families kept keys not made of metal. Back in Saksun, the sky pressed low and the room was colder in the way small rooms get when rain is a rumor under the eaves. She heated water, steam fogging the pane, and when she reached for the teacups in the glass-front cupboard, the whole piece shifted. The back panel clicked and bowed inward a finger-width, as if the cottage had exhaled.

She slid the cupboard away and found a tiny cavity, a paper folded under waxed string, sealed with wax pressed with a rosette almost identical to the one on the driftwood. The vellum smelled of old fish and peat; it was brittle as onion-skin and scribed with shapes that might have been a map and might have been a song. The rosette on the wax braid pricked her—she had seen such a seal before on a bronze button from a Corsican shepherd's jacket, now a resident of her own glass cabinet at home. She didn't believe in coincidences much; she believed in echoes and someone, somewhere, keeping a rhythm.

She took the vellum to Ragna, whose expression closed like shutters in a gale the moment she saw the wax. 'You found this where?' Ragna asked, and when Barbra explained, the woman's mouth went tight. 'That shelf was not empty for you to fill. Some things only stay quiet if quiet people live over them.'

'I didn't take anything from the shore,' Barbra answered, careful with her voice, which she knew could sound like a crowbar if she wasn't mindful.

'But this found me. And it won't leave me alone.' Ragna studied her, not liking and not disliking, measuring what a person might do with what she had found. At last, with a gesture that was more of a surrender than a gift, the older woman tapped the vellum where the lines bunched into a throat. 'When the tide is lowest, the fjord hums truest.

If you think sound is a door, you want Tjørnuvík, not this basin, and you want it at ebb.'

The vellum's lines, once understood as a shoreline, ran with notations like stitches: short slashes beside circles, a string of numbers that looked like a tide table skinned of language. In one margin, in a smaller hand and in a script not meant to be read by many, sat a phrase that didn't need translation: 'when the hum falls, the key points north'. She held the vellum up to the window, and in the slant light she saw the watermarks lift like the ghosts of hands pressed long ago. Somewhere out beyond the cliff-line, a hole in the rock waited for the sea and the right note to open its heart.

It was nonsensical and it was entirely logical, the way storms are reasonable if you understand enough physics and enough poetry. Barbra folded the vellum back into its shape and slid it into a zippered pocket inside her jacket, the floral one that had been her luck more than once. She thought of the time she had been entrusted with an old map in the Atlas Mountains because she had returned a broken charm to a gray-bearded father with more apologies than justifications. She thought of the way she sometimes went out at home in a low-backed dress, pretending the two little dimples above her hips belonged to someone else's flirtation, and smiled at the notion of wearing such softness in a place like this.

She wasn't afraid; fear had long ago learned to lodge itself in her shoulders and she had long ago learned to ease it with movement. The hum crept back through the walls, as if the fjord had been waiting for her to make up her mind. She packed light: notebook, flashlight, a thin coil of rope, gloves, a whistle, and a scarf because wind had teeth here. Her sneakers had dried on the radiator and she laced them tight, tucking in the ends as if she were being watched by a grandmother who hated untidiness.

Outside, the night sat like a sheep near sleep, only its breathing enough to remind you it could startle. The path to Tjørnuvík would be slick in the dark, but the bus ran early—early enough to drop her at a road that turned to gravel, gravel that became sheep track, track that became curiosity's own line. The vellum crackled when she moved, a private applause buried in her pocket. She reached the cliff that opened toward the north, the dark seam in the headland a mouth that never quite closed.

The fjord's song came clearer, no longer a background murmur, but a strand she could pluck, pulling a low F from the throat of stone when the trough formed and a higher E when the swell shouldered in. She pressed her palm against the rock and felt the world answer, a hummingbird's heart in basalt. What was a key if not something that created harmony in a lock? The vellum's line that read 'ebb + hum = open' glowed in her thoughts even as kelp fronds reached for the rock like fingers.

The tide was falling; Ragna's words hung in the salt, and the sheet in her pocket told her exactly when the tone should drop true. She breathed with the waves, counted, and imagined the rosette as a compass rose, its petals pointing not just to north, but to a kind of permission. Somewhere under the lip of the cave there would be a hollow or a seam, a place that vibrated when the valley sang its low note and quieted when it didn't. She looked over her shoulder once at the village lights miles behind, shrugged deeper into her jacket, and stepped forward onto a rock polished by a century of secret feet.

When the hum sank a half step and the cave breathed back, was that the sound of a door beginning to open, and if so, what kind of lock was she about to put her hands into?