CHAPTER 1 - The Dragon’s Blood Covenant

Barbra Dender flies to the remote island of Socotra, hungry for an untouristed mystery and a new story for her glass cabinet of artifacts. She takes a whitewashed rental in Hadibu and explores the markets and highlands, where dragon’s blood trees hum in the wind and shattered glass bottles embedded in rock sing a note she cannot explain. An elder hints at a centuries-kept secret—the Dragon’s Blood Covenant—and warns that families guard it fiercely, even as a copper coin and a vial of resin are left at her door with a cryptic line: “Look where trees drink the sea.” A teacher translates a scrap of writing referencing a cave that sings before the monsoon, and night experiments with wind and bottles reveal a coastal blowhole. At dawn, the receding tide exposes a fissure aligned by the markings on the coin, giving Barbra her first concrete clue: a sea cave near Qalansiyah where the trees nearly touch the surf. Just as she steps toward it, someone behind her speaks her name, setting up the next stage of her seven-chapter quest to earn trust, unlock a guarded legacy, and uncover a secret instrument of winds that families have kept hidden for centuries.

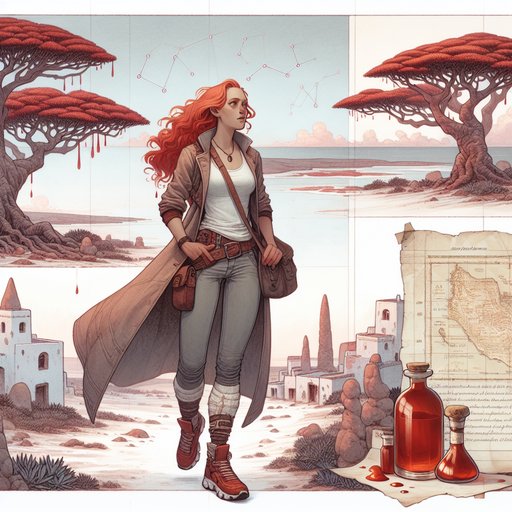

From the plane’s rounded window, the island looked like a fossil rising out of turquoise, its limestone shelves pale and riven as knuckles. Barbra pressed her forehead to the cool plastic, red hair slipping from under a loose band, freckles splayed across her nose like constellations she refused to admire. Thirty-one had taught her a private symmetry: go where the guidebooks hesitate, listen when most people perform, tuck away what others overlook. Socotra had lived in her notes as a question mark for years, a place of winds and dragon’s blood trees and rumors that fishermen heard songs in stone before monsoon.

She smiled, feeling the familiar wedge of anticipation and ache where fear should have been but never was. On the tarmac at Hadibu, the air smelled of salt and something medicinal—resin warmed by sun, or dreams cured into hardness. She wore tight jeans and her blue and white Asics, dust already gathering in the mesh, a charcoal tank top breathing with the heat. She could have painted on a different face for a new country, but she hardly ever bothered; makeup felt like a lie, and besides, she never trusted mirrors in places she hadn’t learned yet.

Her freckles irritated her anew as a boy stared too long, then shyly looked away as if freckles were a language he almost understood. The island’s mountains to the north were hazed in a veil of heat, but the sea to the south looked freshly washed. Her rental was a whitewashed house two streets from the market, a rectangle of shade and ceramic, with a flat roof where laundry lines hummed like taut strings. Inside, the rooms were spare and clean, green glass bottles lined along a sill, their mouths dust-soft and waiting for the wind.

She set her duffel on a low bed, lifted out a floral denim jacket for the cool night, and slid a pair of Louboutins to the back of the closet as if tucking away an unnecessary secret. She had plenty of jackets for plenty of selves, but here she needed the one that didn’t mind rock and salt. Barefoot, she padded to the window and watched two boys chase a goat along the alley, its hooves tapping a rhythm she wanted to learn. The market breathed around her like a gentle creature: fish scales flashed, onions shone, spices rasped under the sudden pat of a merchant’s palm.

She paused at a stall where red resin mounded like tear-shaped coals, their surfaces slickly veined; the woman behind it had hennaed fingertips and a smile held closed like a hinge. “Dragons cry when the wind forgets them,” the woman said, English brittle but adequate, and Barbra heard the confidence of a phrase repeated often enough to become true. She bought a small lump and rolled it in her palm, its smell sharp and green, a lady’s perfume stripped of its pretense. Her grandparents had taught her to listen more than speak—after the car accident, silence was the safest place—and the woman’s silence after the proverb vibrated with the weight of an unfinished story.

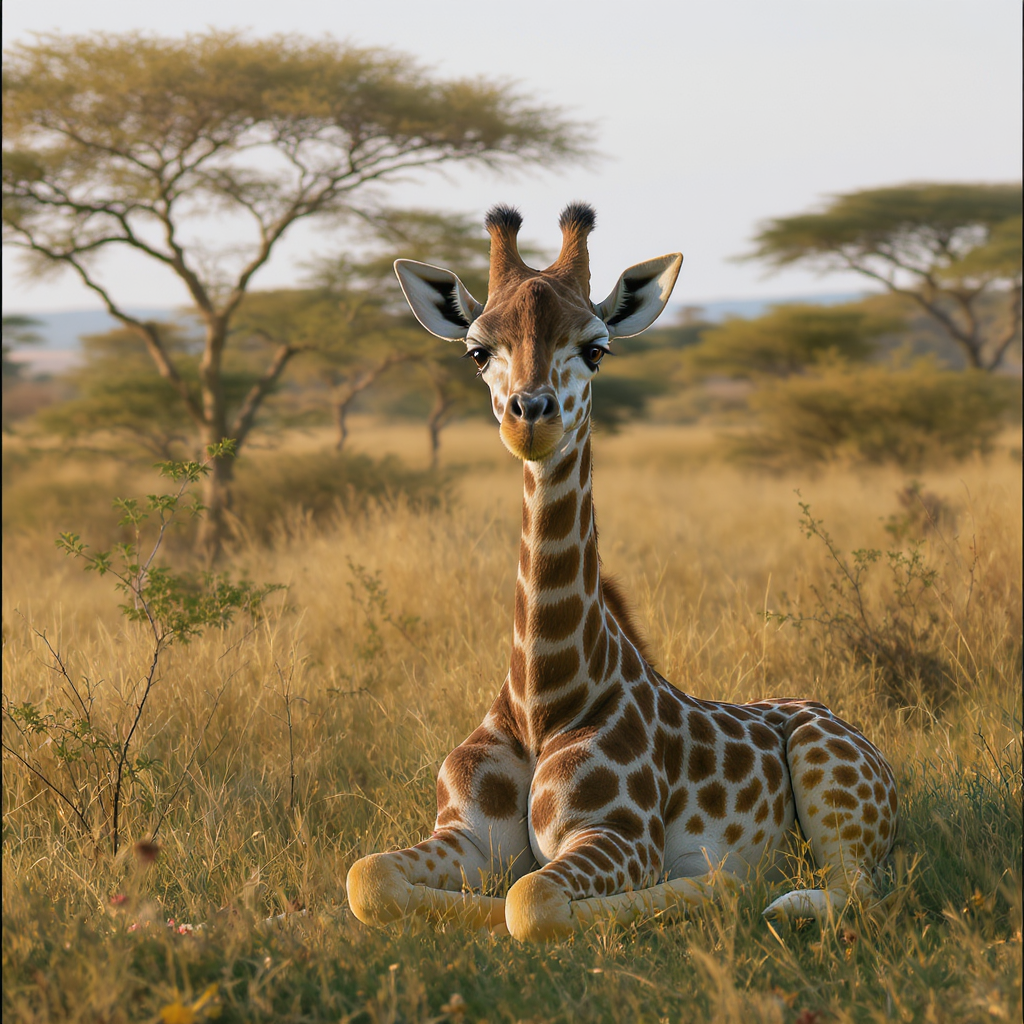

In the afternoon, she hired a battered truck and a driver barely older than the truck to reach Diksam Plateau. The road woke a different set of muscles in her legs, every jostle speaking a private language to the strong cords she’d earned on long walks in other countries. When she stepped onto the plateau, the wind peeled a layer off her thoughts and left only their clean bones. Dragon’s blood trees rose like inverted umbrellas, their crowns massively held against the blue, their trunks scarred like the wrists of giants.

The entire place felt designed and purposeful, as if some arithmetic lay just beneath the dust. As she walked, a low note pulsed under the wind’s shiver, not quite sound, like the memory of a bell heard through a wall. Barbra stopped and held the thought, head tilted, hair whipping her cheeks, and the note came again, a fraction higher, as if searching for itself. She knelt at the foot of a tree and found shards of green glass embedded in the limestone around its roots, their edges worn, their cavities alive with air.

When the wind pushed through them, they sang, a chord made of chance and intention, a voice built of brokenness. She pressed her fingers to a shard and resin slicked her skin; she couldn’t decide if the island had tuned itself or someone had once tuned the island. A shepherd in a turban the color of acacia bark watched her listening and approached in a minim of wary steps. “Foreigners like our trees,” he said, touching one of the green mouths with a scarred knuckle, “but they do not know which sing for mercy and which sing for warning.” His Socotri was heavy in his English, each consonant carrying more weight than the maps had promised.

Barbra told him her name, and he repeated it, trying it on as if it were a borrowed jacket. He drew his hand back when she offered her resin and smiled in apology, then said, “There is a covenant here. Families make promises to wind and stone. You must be careful not to ask the wind to break them.”

Integrity was her talisman; she wore it the way some women wore a crucifix or others a chain of polished pearls.

“I don’t want to break anything,” she said, knowing how little that mattered in the calculus of old secrets, knowing her curiosity had teeth regardless. “I only want to understand who tuned the island.” He looked past her to the horizon and said something in Socotri that could have been a blessing or a dismissal, then took her by the elbow to guide her to a crescent of rock half-hidden by scrub. A spiral had been scratched into it, not compass-true but purposeful, and at the center the faint outline of a tree was inset with green bottle glass. The spiral tugged her attention inward, as if answers were a current and she’d just stepped ankle-deep.

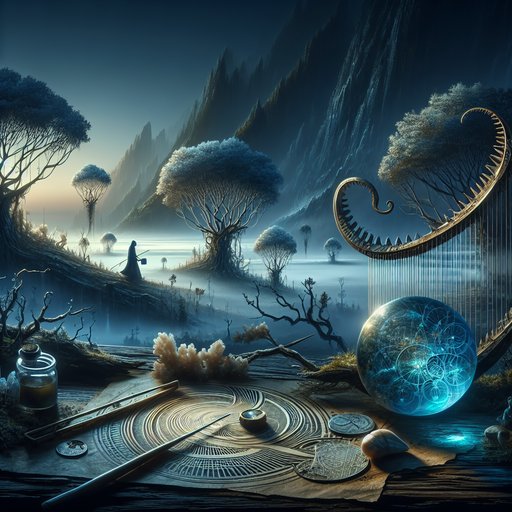

Back in Hadibu as the sun sighed and dropped, she carried her notes to the roof and let the evening chill settle against her skin. She shrugged into her floral denim jacket and breathed the damp that climbs out of stone after heat. Her grandparents would have liked this roof, she decided; her grandfather would have tested the railing with an engineer’s knuckles, her grandmother would have woven the laundry lines into a harp and wondered what winds could play. They had made her into a hardy reed, able to bend, able to sing in new currents without snapping.

Alone, she had learned to draw a circle in air with her finger and step inside it, calling it home for as long as necessary. The next morning she walked west along the beach at Detwah Lagoon, the sand so pale it looked like a rumor of snow. In the silky gray of a wave’s give-back, something flashed, and she knelt to brush away grit from a half-buried bottle, its glass thick and bubbled like old breath. Inside, a strip of paper clung to the glass by damp: writing that wandered like vine, no letters she knew, but with occasional blooms that looked like symbols she’d seen scratched on the plateau’s rock.

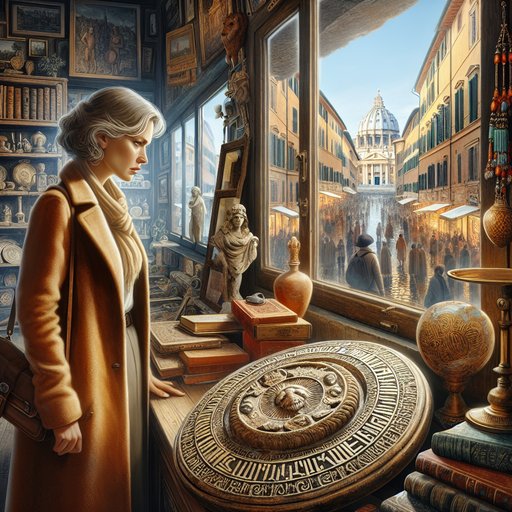

She held it to the light and saw that the ink had bled into a palimpsest of lines, the ocean rewriting whatever was written even as it preserved it. The bottle sang when she tipped it, a thin note sliding up through the mouth, and the hair on her arms lifted as if remembering the plateau’s chord. She found a school where a teacher had hung maps of oceans and rivers like birds across a wall, and the woman who greeted her wore a scarf the color of low tide. “I am Zahra,” the teacher said when Barbra explained her need with a smile and a sketch, and Zahra’s lips made a quick line of thought when she saw the slip of paper.

“Socotri,” she said, and touched a symbol with her index finger, its nail neatly squared and clean. “Old style. It says something like ‘Listen for the cave before Kharif, when the bottles sing to frighten the wind.’” Zahra glanced at the door behind them and lowered her voice. “Some families believe the wind can be tied.

They will not like this paper in your pocket.”

Later, hunger forgotten in the thrum of curiosity, Barbra wandered back through alleys trimmed in shadows and found a parcel at her door under a stone, wrapped in palm leaf and tied with thin rope. It felt heavier than it looked, and when she unwrapped it on the kitchen table, a hand-sized copper coin slid out, its face stamped with a tree whose crown flared in geometries like sunbursts. The other object was a small blown vial filled with dark red resin, the kind that looks like congealed sunsets; it had a cork stopper sealed with wax. There was a scrap of paper as well, in the same looping script, but this time one line was in careful, unfamiliar English: Look where trees drink the sea.

Barbra touched the coin’s raised lines and felt the ghost of a map wearing an innocent costume. Night salted the edges of the city, and the wind learned a different grammar as it came down from the mountains to kiss the shore. She carried two of the market’s green bottles to the rocks by the water and set them into natural holes, their throats lifted like opinions. When the gusts came steady, the bottles spoke, one thin and one stout, a spread of notes like someone walking their fingers across a harmonium.

The sound launched a thought from the day’s conversation: a cave that sings before Kharif, the monsoon that would soon command this island like an old general. She crouched and listened and realized the notes darkened when the water pushed into a crevice elsewhere under the rocks, the air compressed and released like a stanza. She experimented until the tide bit higher at her sneakers and the bottles sang less and more at the same time, the way questions do when you approach them too directly. If the island had a mouth for its song, it would be a blowhole or a narrow crack where air and water struck an agreement under pressure.

Qalansiyah’s cliffs came to mind, where the limestone was riddled with sea-holes and wave-gnawn arches that had definitely learned to speak. The coin’s rim had tiny notches around the tree—twenty-one—and when she held it up to the white slice of moon, the notches made her think of a calibrating mechanism, a way to count on a horizon. She slept briefly and poorly, the vial of resin on the nightstand like a small heart that had chosen to rest beside her own. At dawn, she walked toward Qalansiyah, the road spooling behind her like thread, her Asics tapping a metronome.

In the pink hush before the sun cleared its throat on the waterline, she found the first of the cliffs, their faces streaked with whites and grays and old black tears where waves had reached. Her tank top was cool against her shoulder blades, her floral jacket zipped, salt already making its own flowers on the denim. The tide sucked itself out like a fast inhale, revealing a lace of shore that only morning and luck could show. There, in the base of a rock where a dragon’s blood sapling bent towards the spray, was a fissure as tall as her thigh, the edges scored with figures that rhymed with the spiral she’d traced inland.

She fitted the coin’s stamped tree to the carved one on the fissure, aligning crown to crown, and felt the coin click into a shallow cut as if pressed exactly where it had been pressed a hundred times before by unseen hands. The notches along its rim found corresponding bites in the stone, and the alignment pointed not inward but sideways, toward a shadowed arch further down the reef. “Look where trees drink the sea,” she murmured, and the sapling beside her trembled, or maybe that was just the wind pinching the morning awake. A small wave shouldered into the arch and a long, low note unfurled from within, familiar as a memory she hadn’t made yet.

She stepped toward it, heart hammering in that steady, composed way it had when she’d already decided to dive deeper, when behind her someone spoke her name in a voice soft and certain—“Barbra”—and she turned, pulse and questions colliding: who else knew the song, and what would they do with her first clue?