CHAPTER 1 - Silk Shadows at Dawn

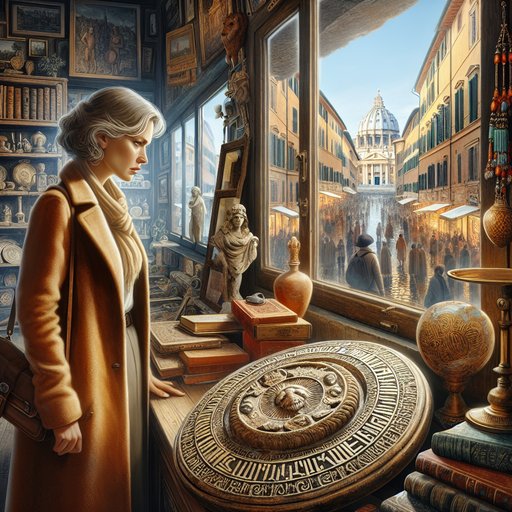

At sunrise in Valencia, Inspector Juan Ovieda is called to La Lonja de la Seda, where the body of Blanca Ferrán, a young archivist tied to the Generalitat’s heritage projects, lies beneath the coiling stone pillars. Sparse evidence surfaces: a smeared orange oil scent, a salt-crusted scuff, esparto fibers, a tampered camera feed, and a missing phone. Rumors of high-level interference swirl as a government conseller, Mateo Vives, arrives flanked by aides, and an influential shipping patriarch, Víctor Beltrán y Rojas, maneuvers to keep the press at bay. Juan, a 42-year-old homicide inspector known for his integrity and haunted by his brother’s overdose, braces for political complications while juggling his base of operations between the Jefatura on Gran Vía and a borrowed office near the port. Amid institutional pressure and whispers of a missing donation ledger, Juan unearths a cryptic bronze-and-enamel token bearing Valencia’s bat emblem hidden at the scene. He cannot place the object’s origin or purpose and senses it is the first thread of a knot binding power, money, and history. The chapter closes on Juan’s uncertainty as he wonders what the artifact is and who planted it.

Valencia woke beneath an ochre wash that made stone glow like bread crust, and the ringtone dragged Juan from the tangle of sheets in his riverside apartment. He lay for a beat, listening to the old Turia parks turn from shadow to green in the first bird calls beyond his blinds. The brass Saint Michael medallion on his nightstand glinted; he pressed it between thumb and palm the way his mother had once pressed his hand before an exam. Duty over sentiment, he told himself, swinging his long legs to the floor and feeling the cold tiles kiss his feet.

By the time he buttoned his sand linen jacket and knotted a narrow silk tie, the call from HQ had sharpened into a single instruction: La Lonja, now. He jogged downstairs, the elevator too slow for the city’s breathless minutes, and stepped into a sky so clear it almost rang. At 1.88 meters and still lean from pre-dawn runs through the Turia gardens, he moved with a steady, quiet pace that made people part without quite knowing why. His short-cropped black hair, flecked with grey, caught the light like graphite, and his thoughtful brown eyes thickened behind focus the way they always did when politics awaited.

The Moto Guzzi balked once before turning over; the old engine coughed and settled into a growl he trusted more than most colleagues. He slipped the medallion into his pocket and let the riverbed wind peel the sleep from him as he arrowed toward the city’s Gothic ribs. La Lonja de la Seda rose in pale triumph, its stone warmed by dawn, the twisted pillars like petrified ropes frozen mid-sway. Blue tape fluttered, held by uniformed officers whose breath made steam wreathes in the shaded courtyard.

Tourists who had woken too early or slept too anxiously lurked at the edge like cats, eyes bright with bad curiosity. He flashed his Policía Nacional ID and stepped over the cordon, his scuffed Oxfords squeaking on the worn slabs with each calculated footfall. Inside, the air was cool and smelled of wet limestone and old varnish. She lay on the flagstones as if interrupted mid-gesture, one hand curled near a column’s base with its carved citrus leaves and angels.

Late twenties, early thirties, hair like dried fennel, blouse torn not violently but by the persistent insistence of struggle. A dark band marred the delicate throat; ligature marks that would photograph like accusations. There was a smear on the stone close to her left hip, faintly oily, bearing the bitter-sweet note of orange peel rubbed between fingers. No wallet, no phone, and an empty space where a lanyard had rubbed a paler line over time.

“Blanca Ferrán,” murmured a young uniform with a clipped beard, passing Juan a file already smudged with haste. “Archivist, contracted with Patrimoni. She was on a late inventory for tomorrow’s donor breakfast.” The words slotted into place with a weight he could feel in his shoulders, a weight he remembered from hauling nets with his father along El Cabanyal’s beach. Donors meant money, money meant names he would recognize, and names like those didn’t like dying in public buildings or being associated with anyone who did.

He crouched, knees whispering in linen, to study the ligature’s angle and the ghost fingerprints of a struggle on her wrists. He called for Remei, the forensic tech with thin patience and a magician’s hands, and let his gaze catalog what his instinct already suspected. No signs of sexual assault; the violence was purposeful, narrow, almost businesslike. A scuff mark near the entrance held a sheen crystallized into a crust like old sea spray, salt encircling the rubber sole impression of a boot with a chipped heel.

From the underside of a nearby table came a tiny fiber, green and rough, the esparto rope that still bound Valencia’s memory of sacks and ships. One of the security cameras blinked blankly when he looked up; its light stayed dead under the poke of a pen. “Feed’s out from 23:40 to 00:15,” Remei said, crouching, white-blonde hair tugged into a severe knot that meant she was annoyed. “Someone popped the housing, looped a… Jesus, a driver plugged right into the junction.

Amateur in looks, pro in timing.” She snapped a latex glove, stretching it with a note of finality. “You’ll want to know who can walk in without the alarm screaming.” Juan nodded, eyes moving from the dead camera to the shaded loggia, to the open sky that felt suddenly complicit. By the time Sergio Llorca, his partner with the battered laugh, arrived, the first whispers had thickened into rumor. “Madrid called,” Sergio said, rubbing a thumb along his jaw as if polishing the words into something more workable.

“They want to be kept informed, which means they want their hands in the bowl but none of the mess.” Juan felt the familiar tightening in his chest that work did when power put on its quiet shoes and tiptoed in. The unsolved overdosing of his brother years ago surged unexpectedly behind his ribs; he swallowed it down with old practice and kept his voice level. He followed the faint trail that scent left, the bright bitter of oranges rubbing against the must of history, and found a smear on a door leading toward the chapter room. The old wood had absorbed the oil and given it back as a translucent thumbprint with a slight tremor in its ridge lines.

“She fought,” he said, softly enough that only the stone heard, and he touched the medallion in his pocket like a prayer he no longer believed in but repeated anyway. The orange oil…it could be from the custodians’ cleaning supplies, but the time didn’t fit, and cleaning crews were never this careless with establishers of heritage. He wrote oranges in a notebook margin, then circled it twice. Outside, the donors had begun to gather like a weather front, and with them the people who steered them into storms and out again.

Assistant Conseller Mateo Vives appeared in a slate suit as if materialized from a press release, skin ruddied by summer and eyes that narrowed intellectually but never emotionally. “Inspector Ovieda,” he said, smiling carefully, as if shaking hands with a test. “We must avoid unnecessary alarm; the breakfast will be rescheduled. You understand the cultural calendar cannot lose momentum.” Juan met the smile with his own version, a smaller thing that fit inside a pocket and added no warmth.

“You’ll have my cooperation,” Vives added in a tone that meant the opposite when necessary, an aide hovering like a ghost at his left shoulder with a tablet. “And our press office will handle statements. Patrimoni has nothing to hide.” Juan’s brown eyes flicked to the aide’s screen where a list of names slid past, donors sorted by family. Not nothing, he thought, and not now.

“We’ll need a roster of everyone with overnight access,” he said, letting the plea read as procedure rather than challenge. Beyond Vives stood a man who didn’t wear a badge but wore importance like a second skin: Víctor Beltrán y Rojas, the shipping patriarch whose company flag dotted the port like a succession of red warnings. His silver hair was combed a fraction too perfectly, his jaw still a machine despite age, and his mouth spoke softly to a PR woman who quietly bled reporters away from the cordon. The Beltranes had made money before Franco and after Brussels and had learned how to be amiable without ever saying yes.

Their presence at a heritage breakfast made civic sense and private leverage. When Beltrán’s gaze brushed Juan, it felt like two fencers noting the distance between their blades. “You’re based at Gran Vía, aren’t you?” Vives said lightly, as if they’d moved on to weather. “We can make you comfortable at the Palau for briefings.” Juan thought of the Jefatura Superior de Policía’s marble corridors, of his scuffed shoes squeaking down them, of how every briefing would turn into a staged conversation.

He preferred the disorder of the borrowed room near the Aduana at the port, walls plastered with printouts, the fan clacking with the small, honest violence of old machines. “I’ll split time as needed,” he said, and watched how the conseller’s smile thinned when it could not claim him entirely. Remei flagged him with a wave, gloved fingers glinting powder. “Trace under her nails,” she said quietly.

“Blue pigment, ultramarine, the kind you get on restoration palettes or pricey design workshops. And something else—smells like neroli.” Neroli meant distilled orange blossoms, the upscale cousin to the peel’s bitter oil. The twin scents of the city’s past and its present were now a chorus, too harmonious to be coincidence. The press surged and retreated in little waves as the PR woman, Inés Pardo, directed murmurs like an orchestra conductor.

“Inspector,” she said with a brightness that did not survive the distance to her eyes, “we’ll coordinate on messaging to avoid panic among donors. This building should be a sanctuary.” He filed away the word sanctuary; history never kept its sanctuaries sealed. “We coordinate on facts,” he replied, and her smile hardened into something with teeth you couldn’t see. Back inside, the monuments of trade cast long bars of shadow that kindled and cooled as clouds sailed impossibly slow.

Sergio returned with coffee so strong it bullied the tongue. “Security list is a sieve,” he said. “Freelance crew packing chairs, caterers, a piano tuner at 18:00, three custodians, and a late delivery from a floral atelier called Naranjal.” Juan chewed the name gently and then wrote it next to oranges, then beneath that wrote Beltrán with a question mark he let bleed through the paper. In the chapter room, the tail end of a wheelchair scuff told a small story against the floor that made him pause, but it was the absence that grew loud.

A ledger stand sat empty, dust shifted in a rectangle where something had rested recently, leaving a ghost print and a faint grit ring. “What was here?” he asked the custodian, a woman in her sixties wearing a key ring that sounded like a muted tambourine when she moved. “Temporary donor ledger,” she said. “For the breakfast’s acknowledgement.

Last I saw, Blanca was checking names at nine.” The space felt suddenly like a missing tooth in a smile. The sun had climbed enough to catch gold highlights in the carvings of merchant ships, bats, and angels that haunted the brackets. Juan, kneeling to pick a thread from a bench’s shadowed underside, felt his medallion bump his thigh. The thread was silk, dyed indigo, cut sharp as if knifed.

He returned to the bench itself, traced the underside of its cold lip, and his fingertips skittered along something that didn’t belong. He reached up into the gloom and eased it out with the deliberate care of someone lifting a sleeping child. The object fit his palm, no heavier than a wallet but with an authority that stiffened his wrist. Bronze, or a copper alloy, aged to a verdigris that deepened into pooled shadows where a motif was incised then filled with enamel so blue it hurt.

The motif was Valencia’s bat, stylized, wings spread across a circle bordered by a ring of tiny notches like the teeth of an astrolabe, and beneath it a cluster of dots arranged in no language he knew. Around the edge ran letters rasped by time: Latin, perhaps, or a bastardized chant recognizable only to a few. It was not a key, not a medallion, and too careful to be a tourist trinket. Remei leaned close, breath shallow to avoid fogging it.

“What the hell is that?” she whispered. Juan shook his head, the muscle in his jaw a small, steady drum. His childhood knew ceramic shards that told stories, fishermen’s tokens rubbed smooth in pockets, and saints’ medals flared by kisses, but nothing like this. It felt both old and new, a mimic or an heirloom or a counterfeit that had forgotten the art of lying completely.

He turned it over; the back was plain save for a hairline groove and the ghost of a fingerprint that wasn’t Blanca’s. He wrapped it in a cloth and slipped it into an evidence pouch, his palm emptying as if it had relinquished a small silence. Outside, the murmurs had thickened; a rumor dressed itself in confidence and strutted close—the word suicide spiked with the word accident and both untrue. He looked at the dead camera, the missing ledger, the orange oil kneaded into wood by hurried hands, and the shipping patriarch holding sums in his smile.

He looked at the conseller’s careful stance, at the PR woman herding memory away from microphones. The city’s baroque façades would hold their breath for a week, he knew; pressure had a calendar. Back at the Jefatura on Gran Vía later, maps of Valencia sprawled across his office wall like veins, case photographs pinned in constellations he could not yet name. He requisitioned the borrowed room near the Aduana, already imagining its fan’s uneven tick punctuating long nights on cheap coffee and the smell of the port.

The brass medallion warmed against his leg as if agreeing to keep sleepless watch. His pen hovered over the word bat, and he drew a line to oranges, and another to Beltrán, and another to Blanca’s blue pigment. Then he stopped and made a new circle labeled artifact, as if naming it might make it less unknowable. He thought of his brother’s thin wrists, of a night when orange blossoms had covered the trash smell near a club and made wrongness smell like spring, of men who moved money until the blood faded to numbers.

Maybe Blanca had touched the wrong page, whispered the wrong name, added the wrong donor to a list that was not supposed to exist. Maybe the artifact was not hers at all, maybe it had been planted, a heraldic breadcrumb or a taunt. He closed his eyes and saw the bat’s wings spread against an enamel sky. What was it, who wanted him to find it, and how had it found its way beneath a stone bench in the heart of Valencia?