Eat, Poop, Die. It is a crude mantra for a sublime truth: animals transform worlds by cycling nutrients, fertilizing seas and soils, and stitching life into long, looping feedbacks. Humans, by contrast, have built a culture that mistakes disposal for progress, a one-way chute from extraction to landfill that severs the very loops that keep us alive. Rivers once ferried myths and meanings; today they are made to carry what we cannot be bothered to steward. If we want living waters and living futures, we must relearn reciprocity from the messy elegance of ecology and hardwire it into the institutions that govern the blue half of our planet.

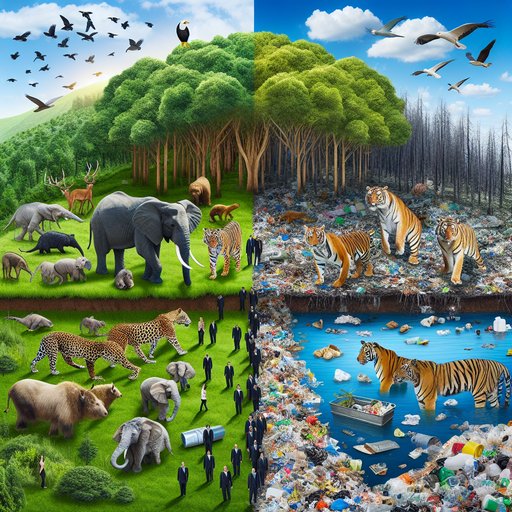

Anthropology begins with the obvious that we forget: cultures are ecosystems of meaning, and ecosystems are cultures of matter. Animals do not merely decorate nature; they construct it through the basic acts of feeding, excreting, and decomposing — the unsentimental choreography of eat, poop, die [1]. That choreography keeps nutrients moving, fuels blooms, and underwrites the resilience we take for granted when we breathe, drink, or harvest. Our species has been gifted ringside seats to this performance and, increasingly, we’ve dragged a bulldozer into the theatre.

The question is whether we will recode our systems to partner with those cycles rather than crush them. The mythology of modernity says waste disappears. In reality, the anthropology of the checkout aisle tells a different story: the throwaway is a design decision that trains us to consume and toss without consequence. In many low-income neighborhoods, packaging-driven convenience stands in for infrastructure, and people are forced into high-cost, low-agency loops that look efficient to distant accountants and feel extractive on the ground.

A disposable culture is an oxymoron because cultures are, by definition, intergenerational — they braid ancestors to descendants. Throw everything away long enough and you eventually throw away the future custodians of your own story. The sea is where this denial gathers. International waters have been a legal and moral blur, a blue commons where accountability thins, even as currents bind continents together.

That is why the High Seas Treaty matters: it opens the door for global ocean conservation, creating a pathway to protect biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction and to curb the tragedy-of-the-commons logic that has depleted and polluted the high seas [2]. If animals are the couriers of fertility — moving nutrients across space and time — then the governance of those spaces is not an abstraction. It is the scaffolding on which biological cycles either thrive or falter. Yet even promising scaffolding creaks under old habits.

Consider the race toward mining the deep seabed, promoted as a solution to terrestrial scarcity and the energy transition’s hunger for metals. Trust in the International Seabed Authority — the very body meant to steward this frontier — is fragile, and researchers have outlined practical reforms to strengthen transparency, participation, and scientific rigor [3]. Anthropologically, fragile trust is a signal that a community of fate has not been credibly formed. When the rule-maker is doubted, the rules invite corner-cutting.

And when the substrate is the seafloor, the stakes extend far beyond any single lease area. This isn’t an abstract seminar topic; it is on the public syllabus. In India, for instance, Indian Ocean mineral exploration is prominent enough to feature in current affairs briefings, underscoring how quickly seabed extraction has leapt from expert debate to mainstream policy preparation [4]. The speed of that normalization outpaces our civic conversation about what kind of ocean culture we want.

We should be honest: a civilization that celebrates the animal economy of eat, poop, die only when it can be monetized, while bulldozing the slow ecologies that make it possible, is enacting a ritual of self-contradiction. So here is a counter-ritual. Let us treat nutrient loops as moral teachers. Animals do not stockpile; they circulate.

They do not outsource their leftovers to nowhere; their waste becomes someone else’s feast [1]. Our material systems should mirror that pedagogy by building return pathways into every product and policy, especially where rivers meet the sea. Call it a deposit-return ethic if you like, not as a nostalgic nod to bottles past, but as a cultural commitment: nothing leaves a factory or a port without a guaranteed route back into value. The point is less the specific mechanism than the obligation to close loops on purpose rather than by accident.

Hope is not a mood; it is a method. When Nature calls Jane Goodall a "messenger of hope" and recounts her decades of scientific impact, it is naming a stance that has always married observation to stewardship [5]. Goodall’s lesson is not that optimism will save us, but that attention will — attention to relationships, to reciprocal care, to the long arcs that exceed any one budget cycle. Translate that ethos into ocean governance and the High Seas Treaty becomes more than a press release; it becomes a living covenant backed by monitoring, enforcement, and culturally legible stories about why distant waters matter to inland lives [2].

Critics will say that closing loops is utopian while the world is hungry for energy and minerals. But anthropology reminds us that societies choose their scarcities. We can decide to be short on imagination instead of nickel, short on governance instead of cobalt. Strengthening the Seabed Authority’s legitimacy, opening its data, submitting decisions to independent science, and ensuring that those who stand to lose are truly at the table are not luxuries; they are the minimum requirements of a commons we intend to keep [3].

Pair that with precautionary pacing — a willingness to say “not yet” when knowledge and consent are insufficient — and the ocean becomes a partner, not a mine. Meanwhile, what of the rivers? They once carried myths because people bothered to tell them; the stories were mnemonic devices for responsibility. Today they can carry something better than indifference: they can carry proof that we have learned.

The path runs from headwaters to high seas. Anchor local stewardship in return guarantees. Use the High Seas Treaty to knit protected corridors across migratory routes and spawning grounds [2]. Align national curricula and civil service training — the very forums now studying Indian Ocean extraction [4] — with the ethics of looped systems, so that tomorrow’s officials see circularity as basic competence rather than boutique reform.

Eat, poop, die is not a punchline. It is a primer in humility. Animals show that thriving is a property of circulation, not accumulation [1]. If we absorb that lesson, then seabed policy, river management, and market design stop living in separate silos.

We will measure success by how little ends up as orphaned waste, how much is returned to cycles, and how widely trust is shared in the institutions that guard the commons. Do that, and the rivers will remember their old vocation: to carry our best stories to the sea and bring back rain we can believe in.

Sources

- Eat, Poop, Die. How animals affect the world (Energyskeptic.com, 2025-10-01T08:27:16Z)

- A Sign of Progress: High Seas Treaty Opens the Door for Global Ocean Conservation (Triplepundit.com, 2025-10-02T23:21:38Z)

- Trust in the sea-bed mining authority is fragile — here’s how to change that (Nature.com, 2025-09-30T00:00:00Z)

- UPSC Key: Indian ocean mineral exploration, Postal ballots, and Cybercrimes (The Indian Express, 2025-09-30T12:19:39Z)

- Daily briefing: ‘A messenger of hope’ — Jane Goodall’s impact on science (Nature.com, 2025-10-02T00:00:00Z)